Bookplates (and ghostly traces of adhesive), stamps, and signatures tell of where this volume, resting in the Chancellor Green Rotunda, has been. It’s a copy of Antony and Cleopatra from the Works of Shakespeare edited by R. H. Case. Note, especially, the inscription, “Willard Thorp,” in the top right corner and continue through the end of this post.

“The history of book-collecting is a record of service by book-collectors—a service performed sometimes deliberately, sometimes unconsciously—to the republic of letters,” wrote John Carter in 1948, referring in the same sentence to the Parrish Collection of Victorian Novelists at Princeton.[1] Carter, whose books remain classics in the rare book field, was a professional book dealer and Reader in Bibliography at Cambridge University when Taste & Technique in Book Collecting appeared, four years after Morris L. Parrish’s bequest to his alma mater. News of the gift, as well as a sense of its importance, evidently got around.

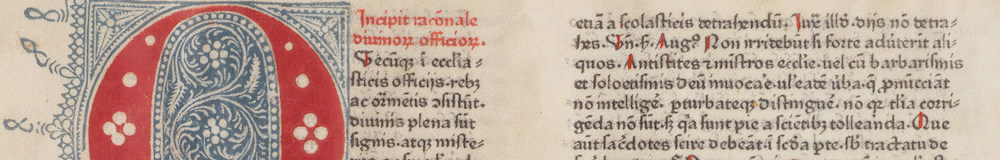

The Parrish Collection deserves the recognition it received, containing as it does over 6,500 novels, periodicals, graphics, and examples of ephemera in English and American first and subsequent editions, as issued, and in exceptionally high condition. The Robert H. Taylor Collection also astonishes, illustrating the scope of English literature from the 1300s to the 1920s in over 4,000 rare books and 3,300 manuscripts. The contents of the Scheide Library, which currently include the first fourteen printed editions of the Bible, speak for themselves.

Not all collections at Princeton, though often the products of careful assembly by private hands, share a setting in Rare Books and Special Collections at the PUL. Some were also established in honor of scholars or alumnae, but are largely overlooked in well-trafficked campus areas. Others tuck themselves away into remote locations that see fewer visitors over time. Some are transformed at the requests of changing patrons; others are simply waystations for books that served bygone needs.

There are pockets of books around Princeton that run the gamut of miscellaneous libraries, from the little-known and the even less asked about, to the reinvented and the recently installed. Most reflect the commitments to scholarship of private individuals whose legacy endures in traces of ownership such as bookplates and inscriptions, even if their collecting habits lose their legibility over the years. All invite a poke through the shelves – however dusty – and a peek between the covers – however delicate – with something of the confidence of Morris L. Parrish himself, that a book “loses its purpose of existence” if it cannot be read.[2]

~~~

The Van Dyke Library sits inconspicuously on the ground floor of the Old Graduate College, at the end of a sunken stone corridor removed from the main courtyard. Card access is restricted to residents of the GC, moreover, though perhaps in keeping with the dedication of the library in 1934 to the specific needs of graduate students. The library was organized in the memory of Paul van Dyke, Class of 1881 and subsequently professor of history at Princeton, by a committee of GC residents who selected “current books of biography, history, science and philosophy, but no fiction” for the stacks.[3] The original collection, assembled from contributions by university affiliates and purchases by the committee, still stands, although more recent additions have accumulated in the study space.

The Hinds Library also takes its name from Princeton faculty. It serves as an English seminar room in McCosh Hall and contains the collection of Asher Estey Hinds (1894-1943), whose books on literature and literary criticism have blended generously with additions from later donors. Hinds’ books have section and shelf locations penciled in on their inside back covers and often display an unassuming bookplate in the front; an inventive Hinds Library monogram also appears in white at the feet of their spines.  Newer publications often have no indications of previous ownership, but others contain inscriptions or even bookplates of their own. One such example is a book signed by Willard Thorp, who served as Holmes Professor of Belles Lettres and co-founded what is now the American Studies Program in 1942.

Newer publications often have no indications of previous ownership, but others contain inscriptions or even bookplates of their own. One such example is a book signed by Willard Thorp, who served as Holmes Professor of Belles Lettres and co-founded what is now the American Studies Program in 1942.

Hinds’ contemporary in the English Department gave his name to another library space in McCosh, almost directly upstairs from B14. Although the Thorp Library, dedicated in 1991, does not reflect Thorp’s own collection and serves instead as the departmental lounge, it recently welcomed perhaps the newest minor library at Princeton.[4] In fall of 2017, the Bain-Swiggett Library of Contemporary Poetry was installed in 22 McCosh through support from the Bain-Swiggett Fund and committee. As its name implies, the library makes a rotating, circulating collection of contemporary English-language poetry available to the university community, any member of which may borrow a book for up to two weeks and suggest new acquisitions. Updates to the inventory are reflected quarterly in the Bain-Swiggett Poetry Collection newsletter.

The Julian Street Library was established by Graham D. Mattison, Class of 1926, in memory of friend and author, Julian Street. Still housed in Wilson College, Wilcox Hall, it opened in 1961 with a selection of 5,000 books “most frequently in demand by students for broad supplementary reading” and curricular development, growing to 10,000 holdings by the 1970s.[5] Today’s academic demands probably divert attention from the remaining books themselves, which open to the Street Library bookplate and still carry loan cards in back, to the J Street Media Center, which offers access to multimedia software, a recording studio, and an equipment lending program to all undergraduates.

The Julian Street Library was established by Graham D. Mattison, Class of 1926, in memory of friend and author, Julian Street. Still housed in Wilson College, Wilcox Hall, it opened in 1961 with a selection of 5,000 books “most frequently in demand by students for broad supplementary reading” and curricular development, growing to 10,000 holdings by the 1970s.[5] Today’s academic demands probably divert attention from the remaining books themselves, which open to the Street Library bookplate and still carry loan cards in back, to the J Street Media Center, which offers access to multimedia software, a recording studio, and an equipment lending program to all undergraduates.

Princeton’s other undergraduate colleges have resident collections of their own, and libraries are fixtures in eating clubs as well. Campus Club, which was turned over to the university following its closure in 2005 after 105 years of activity, still stocks a number of books donated by club members, deaccessioned from the PUL, and removed from Lowrie House, to name just a few provenance highlights.[6] The Campus Club Library sits on the second floor of the building, although books also line the walls of the Prospect Room one floor down.

Princeton’s other undergraduate colleges have resident collections of their own, and libraries are fixtures in eating clubs as well. Campus Club, which was turned over to the university following its closure in 2005 after 105 years of activity, still stocks a number of books donated by club members, deaccessioned from the PUL, and removed from Lowrie House, to name just a few provenance highlights.[6] The Campus Club Library sits on the second floor of the building, although books also line the walls of the Prospect Room one floor down.

Books from the Walter Lowrie House found their way to the library in Prospect House as well – perhaps somewhat ironically, given the president’s opposite relocation in 1968.[7] The Prospect House Library resembles other minor collections around campus: its holdings, shelved floor to ceiling in a ground-floor room of the faculty club, are an assortment of recruits from the PUL, the Princeton Club of New York, private individuals, anonymous donors, and even the Julian Street Library, mentioned above.

Probably the largest “miscellany” of non-PUL books at Princeton, with perhaps the widest range of publications, occupies the two-tiered study area in the Chancellor Green Rotunda. The present iteration of the space opened in 2004, after a renovation that restored and upgraded Chancellor Green and East Pyne Hall, and the shelves were apparently rumored to remain empty.[8] A variety of books and journals, old and new, some inscribed or containing bookplates, has since relocated into the area from faculty offices and other local bookcases.  One record indicates a donation by the Princeton University Archives and the Princetoniana Committee of the Alumni Council, but the books in question have by and large mingled with foreign language journal runs – mainly French and German – and worn paperbacks of classic texts. Curiously, Chancellor Green and East Pyne together served as Princeton’s university library from 1897, when the collection outgrew the former building, until 1948, when its 1.2 million volumes found ampler residence in the brand new Harvey S. Firestone Memorial Library.[9]

One record indicates a donation by the Princeton University Archives and the Princetoniana Committee of the Alumni Council, but the books in question have by and large mingled with foreign language journal runs – mainly French and German – and worn paperbacks of classic texts. Curiously, Chancellor Green and East Pyne together served as Princeton’s university library from 1897, when the collection outgrew the former building, until 1948, when its 1.2 million volumes found ampler residence in the brand new Harvey S. Firestone Memorial Library.[9]

Please comment on any prospective additions to this survey of inconspicuous book deposits in the box below. Special thanks for their valuable research assistance to John Logan, Literature Bibliographer, and Stephen Ferguson, Associate University Librarian for External Engagement.

[1] Carter, John. Taste and Technique in Book-Collecting: A Study of Recent Developments in Britain and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1948, p. 5.

[2] Wainwright, Alexander. “The Morris L. Parrish Collection of Victorian Novelists.” Princeton University Library Chronicle, Volume LXII, Number 3, Spring 2001, p. 366. http://libweb2.princeton.edu/rbsc2/libraryhistory/195-_ADW_on_Parrish.pdf

[3] “Organize New Library As Van Dyke Memorial: Friends of Late Historian Seek to Endow Non-Fiction Collection for Graduate College.” Daily Princetonian, Volume 58, Number 174, 26 January 1934. http://papersofprinceton.princeton.edu/princetonperiodicals/?a=d&d=Princetonian19340126-01.2.8&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-Friends+of+Late+Historian+Seek+to+Endow+Non%252DFiction+Collection+for+Graduate+College——

[4] “McCosh Warming.” Princeton Weekly Bulletin, Volume 81, Number 7, 21 October 1991. http://papersofprinceton.princeton.edu/princetonperiodicals/?a=d&d=WeeklyBulletin19911021-01.2.5&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22mccosh+warming%22——

[5] “Foreword.” The Julian Street Library: A Preliminary List of Titles, compiled by Warren B. Kuhn. New York and London: R. R. Bowker Co., 1966.

[6] “Renovated Campus Club to become new gathering place for students.” 14 September 2006. https://www.princeton.edu/news/2006/09/14/renovated-campus-club-become-new-gathering-place-students

[7] “Goheen To Move From Prospect House.” Daily Princetonian, Volume 91, Number 145, 17 January 1968. http://papersofprinceton.princeton.edu/princetonperiodicals/?a=d&d=Princetonian19680117-01.2.2&srpos=14&e=——196-en-20–1–txt-txIN-walter+lowrie+house——

[8] “Chancellor Green Offer [sic] New Study Space.” Daily Princetonian, Volume 128, Number 45, 8 April 2004. http://papersofprinceton.princeton.edu/princetonperiodicals/?a=d&d=Princetonian20040408-01.2.3&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-Chancellor+Green+Offer+New+Study+Space——.

[9] Read about the history of the Princeton University Library and see Chancellor Green as it looked in 1873 here: http://library.princeton.edu/about/history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.