Many of the most important discoveries in the study of rare books are the results of fruitful collaborations. In this case, we were confronted by an anomaly: Princeton’s copy of the first printed Latin-Spanish dictionary, Alfonso Fernández de Palencia’s Universal vocabulario en latín y en romance, vol. I (Seville: Paulus de Colonia, 1490), which lacks its title page and introductory ‘argumentum’, begins and ends with single printed leaves from an entirely different book – a Spanish-Latin dictionary printed with a slightly larger fifteenth-century typeface:

Universal vocabulario, 1490 (video)

Whereas these stray leaves seem to owe their survival to having been recycled as binding waste that served as protective endleaves for the Universal vocabulario of 1490, there is some question as to how they became available to the eighteenth-century binder, and whether they may have been selected for their lexicographical content. However, a more central mystery remained to be answered: what exactly was the dictionary that provided these long-forgotten fragments?

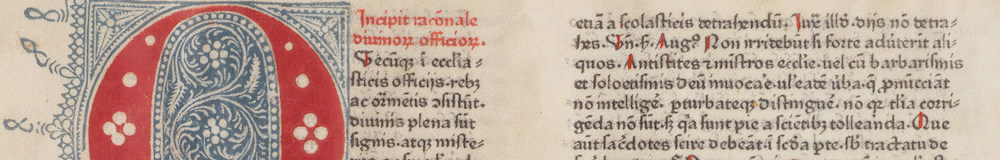

The first fragment, blank on its recto, consists of a short ‘Prologo’ in parallel Spanish and Latin, dedicating a new dictionary to Queen Isabella of Castille and Leon, Aragon, Sicily, and Granada. The second clearly belongs to that dictionary: it contains the Spanish terms Apuesta–Arcaz on the recto and Arco–Arreboçar on the verso (77 terms in total), each with brief Latin definitions that occasionally cite passages in the works of Virgil; the heading ‘dela letra A’ appears in the upper margins. After inconclusive consultations with several experts, the first breakthrough came from Oliver Duntze at the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke in Berlin, the leading research center for the cataloging of fifteenth-century European printing. Duntze was able to provide an almost certain identification of the printers: the types precisely matched those of the Seville press of Meinhard Ungut und Stanislaus Polonus, specifically the state of their types used in 1492.

The date ‘ca. 1492’ was a good match for the status of the royal dedicatee, Queen Isabella (1451–1504), who took the specified title of ‘Reina de Granada’ only after the capture of that territory in January of that year. However, the text contained in these leaves, including the royal dedication, did not match up with any known Spanish dictionary printed during the fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries. None of the bibliographical tools at our disposal or the book historians we consulted could provide an identification of the edition that was the source of these stray leaves; we began to suspect, as had Frederick Vinton, the librarian who oversaw the acquisition of the volume in 1873, that they represented a previously untraced edition – and a potentially important discovery.1

A turning point came in February 2018, when Dr Cinthia María Hamlin, a specialist in medieval literature from Secrit-CONICET (Argentina’s National Scientific Research Council) and the Universidad de Buenos Aires, visited Princeton University Library’s new Special Collections Reading Room and requested to see several early Spanish books. During her visit I inquired whether it would be a distraction to ask her opinion of the mysterious leaves in the Universal vocabulario of 1490. She quickly became fascinated by them, knowing that one does not encounter pages from an unidentified fifteenth-century Spanish dictionary every day. We agreed that the problem deserved much further research, both for the benefit of European printing history and Spanish linguistic history.

Working from digital images upon her return to Buenos Aires, Hamlin investigated the mysterious dictionary, eliminating all of the candidate texts by Antonio de Nebrija and Fernández de Santaella and analyzing the linguistic characteristics of the limited sample of word definitions that the fragments provided. Within a little over a month she made a startling breakthrough. Following up on a suggestion offered by her colleague Juan Héctor Fuentes, she discovered that an anonymous fifteenth-century Spanish-Latin Vocabulario, known only from a manuscript at the Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial (MS f-II-10), matched Princeton’s printed fragments nearly word for word.2

Colecciones Reales. Patrimonio Nacional. Real Biblioteca del Monasterio del Escorial, f.II.10 (f. 17v).

Princeton fragment 2, verso: Arco–Arreboçar (with Latin definitions similar to those of the Escorial MS).

Thus, Hamlin and Fuentes hypothesized that the long-lost Vocabulario represented by the fragments, datable to 1492-93, was the first Spanish-to-Latin (not vice-versa) vocabulary ever printed, preceding Nebrija’s first Salamanca edition (variously dated between 1492 and 1495, but most likely 1494-95). The two scholars’ discovery has been introduced in the co-authored ‘Folios de un incunable desconocido y su identificación con el anónimo Vocabulario en romance y en latín del Escorial (F-II-10).’ Romance Philology 74/1 (Spring 2020), 93-122, and will be developed further by Hamlin in ‘Alfonso de Palencia: autor del primer vocabulario romance-latin que llego a la imprenta?’ in Boletín de la Real Academia Española (forthcoming in 2021).

After further research, Hamlin concluded that the anonymous author of the Escorial Vocabulario, and, therefore, that of the previously unknown printed edition preserved in Princeton’s binding fragments, was none other than Alfonso Fernández de Palencia (1423–1492), the author of the very same Universal vocabulario of 1490 into which the mysterious Princeton leaves had been bound. As Hamlin notes, Palencia’s Universal vocabulario has many of the the same ‘authority’ quotations, highly similar definitions (especially for toponyms), and several of the terms have the same grammatical explanation and thus almost certainly are the works of the same author. This important discovery, too, will be explored in greater detail in Hamlin’s forthcoming article.

Fifteenth-century Spanish printing of any kind is difficult to come by in libraries outside of Spain. It is even more remarkable to have located traces of a previously unknown Spanish edition of that period. Moreover, it is a signal accomplishment to have been able to resurrect an unknown printing of a previously anonymous work of such importance, in vernacular Spanish, and then to augment our knowledge of that text with both a long-lost royal dedication and a convincing identification of its author, one of the most influential Spanish humanists of the fifteenth century. The fields of printing history and Spanish linguistic history have profited mightily from the collaboration that solved this bibliographical mystery.

More about Princeton’s Universal vocabulario of 1490 (EXI Oversize 2530.693q):

The book consists of vol. 1 only, covering letters A-N. Its gilt red-dyed goatskin binding is probably 18th-century Spanish. The earliest known owner was Richard Heber (1773–1833), the English bibliomaniac; this copy was offered in part 2 of the Heber sales, Sotheby’s (London), June 1834, as lot 4689. In 1873 it was purchased by the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) along with an important collection of old books and Reformation pamphlets owned by Dr. Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg (1802–1872), a noted philosopher and philologist at the University of Berlin and father of a famous surgeon. It is possible that Trendelenburg bought the Vocabulario at the Heber sale of 1834, but there may have been unknown owners between 1833 and 1873.

********************

1 Frederick Vinton, the Librarian of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), inscribed the second fragment “This is a great curiosity. It is part of a Spanish Vocabulary entirely unknown to Bibliographers and must have been printed about the same time as this of Palentia in which the Latin precedes the Spanish.”

2 Gerald J. MacDonald, Diccionario español-latino del siglo XV: an edition of anonymous manuscript f.II.10 of the Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo de El Escorial. Transcription, study, and index (New York: Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies, 2007).

This owner’s limited itinerary and the strictly local interest of the Cöthen law book both suggest that the bindery of this book – and likewise the lost Gutenberg Bible – should be localized to Saxony-Anhalt, northwest of Leipzig, during the last decades of seventeenth century.

This owner’s limited itinerary and the strictly local interest of the Cöthen law book both suggest that the bindery of this book – and likewise the lost Gutenberg Bible – should be localized to Saxony-Anhalt, northwest of Leipzig, during the last decades of seventeenth century.

You must be logged in to post a comment.