For its second session of the fall term, the Rare Book Working Group (RBWG) at Princeton University Library asked the question shared by generations of booksellers and readers: “Why pay more?” Its survey of “cheap books” through the ages opened with examples of economizing Virgilian ventures from the early hand-press period, compared the Shakespeare First Folio of 1632 to shilling editions released during the Victorian era, crossed the Atlantic for an introduction to the evangelical pamphlets of Lorenzo Dow, and investigated signs of book ownership in productions of the popular press. Professor Seth Perry (Religion) and RBSC experts, Eric White and Gabriel Swift, highlighted material evidence of cost-effectiveness in American and continental European publications, respectively, while student assistants Miranda Marraccini and Jessica Terekhov spoke to the nineteenth-century reading revolution. A sampling of “inexpensive” rare books was on hand for the interactive portion of the session, during which participants shared observations into the economics of readership as captured in marketing strategies, popular genres, and publishing innovations.

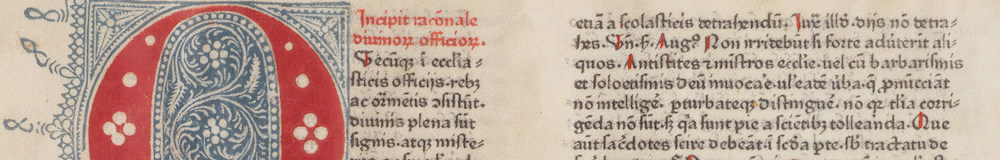

The earliest book introduced was a 1469 folio collection of Virgil’s complete works, followed by a 1510 octavo edition, four times as small. The group related the size reduction to lower production costs and speculated that a 1511 publication of the Aeneid alone, although in quarto format, may have suited tighter budgets by economizing on content.

The juxtaposition between other early modern staples, the first appearance of Shakespeare’s collected works and the first quarto edition of any of his plays (Love’s Labour’s Lost), and a selection of popular anthologies from the nineteenth century was similarly revealing. Leading the race to the bottom in the 1800s were Ward, Lock and Co., whose six-penny Complete Works outstripped and underpriced competitors in 1890. Princeton owns neither this edition (yet), nor Dicks’ shilling Shakespeare of 1866, which sold 700,000 copies within two years of its release upon the 250th anniversary of the bard’s death.

The Works of William Shakespeare, ed. by William George Clark and William Aldis Wright (London: Macmillan and Co., 1884).

Of special note among the anthologies displayed was the Globe Shakespeare published by Macmillan in 1884, two decades after their first Globe venture. Princeton’s copy is unique for its indications – and illustrations – of prior ownership. The book is inscribed on the half-title page by Francis Turner Palgrave, perhaps most famous for editing The Golden Treasury of English Songs and Lyrics (1861) in collaboration with Alfred Tennyson, to his daughter, “Margaret I. Palgrave, with best love from her Father, June 1894.” Turning past Margaret Palgrave’s bookplate on the inside front cover reveals a curious combination opposite the half-title: a magazine clipping of two kittens above a pin commemorating the Shakespeare Festival of Mercy in 1915.

Flower petals are interleaved throughout the book, having been left in long enough to have stained certain pages, and a pasted-down illustration of a hound in profile completes the picture on the back free endpaper. The RBWG agreed that such colorful evidence of ownership provides insight into earlier reading practices and clues to one book’s career through different libraries through the centuries.

With Professor Perry at the helm, the group journeyed abroad and toured the eastern seaboard with Lorenzo Dow, an evangelical preacher known for his eccentric style and far-flung presence. Professor Perry discussed Dow’s early nineteenth-century tracts, several of them brittle pamphlets with creases where they were presumably reduced to pocket size, in relationship to Dow’s appropriation of Thomas Paine as well as his marketing techniques, which included selling publications on a subscription basis and distributing copies through newspaper offices. The highlight of the crop was the fifth printing of the Progress of Light and Liberty, sown and uncut as issued in Troy, NY, in 1824. Perry explained that the value of the text as a physical artifact consisted in its having been spared material accretions by later book dealers, owners, or holding institutions, who would have interfered with the original condition of the 36-page pamphlet. Perry later commented:

The final portion of the session was devoted to a roundtable showcase of “cheap books” over the centuries, from a 1558 medical handbook with censored passages to a number of late Victorian railway reads, called yellowbacks given the typical color of their paperboard covers (see, for instance, Wanted! A Detective’s Strange Adventures). Late eighteenth-century moral tracts, published under the direction of Hannah More (Cheap Repository Tracts), almanacs (Ames’s Almanack Revived and Improved), primers (The New-England Primer Improved), and school prizes (ironically, Colonel Jack: The History of a Boy that Never Went to School) rounded out the survey of affordability, a category in flux almost since the very beginning of Western printing.I think cheap books give us a window onto intimate, portable, active aspects of print culture. Cheap books go places and do things that fancy books typically don’t. Early-American itinerant preacher Lorenzo Dow (the subject of my second book) published a lot of cheap print – pamphlets and broadsides that he carried around with him to sell and to post – and he was routinely worried about them getting soaked in his saddle bags when he traveled in the rain. Seeing that always makes me think what a different approach to print culture his texts represent from, you know, fancy gilded books that would never have found themselves in a wet saddlebag. Cheapness is not always just about class and access to print, but also about print imaginaries – cheapness opens up different ways for producers and consumers to imagine what print can do, and where, and for whom.

The RBWG invites students and faculty in any discipline with interests in book and printing history to its spring sequence, which will feature a program on “East and West” and a tentative visit to off-campus collections. Please contact Jessica at terekhov@princeton.edu to join the RBWG listserv for future updates.

You must be logged in to post a comment.