Question: What could be better for the study of early printed books than examining a copy of a rare 15th-century edition?

Answer: Examining two copies of a rare 15th-century edition.

Thanks to several formerly independent channels of 20th-century collecting, now united, Princeton University Library’s Special Collections owns multiple copies of more than thirty 15th-century editions. We do not consider them ‘duplicates’, as that would imply that they are absolutely identical, and that nothing is to be learned from the ‘second’ copy. Nothing could be further from the truth. Even if every letter of every word printed on every page were virtually identical (with printing shop corrections and other improvements, this is often not the case), the individual copies would still reflect entirely different histories of readership and survival, preserving unique material evidence that may be crucial to the attentive researcher, or of worthwhile interest to the casual student of book history.

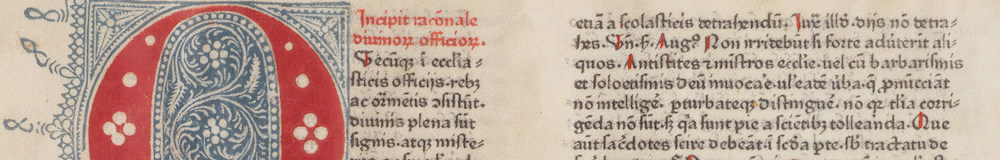

Illustrated below are four examples of 15th-century editions represented by two copies. In each case, one of the copies was owned by Grenville Kane (1854–1943) of Tuxedo Park, New York, whose fine library of early books and Americana was purchased by the Trustees of Princeton University in 1946, while another copy is in the incomparable Scheide Library, long on deposit in Firestone Library but bequeathed to Princeton University in 2015 by the late William H. Scheide (1914–2014), Class of 1936. The first things that strikes most present-day viewers are the differences in their hand-decoration, and in their various bindings – copy-specific features that were added only after the individual sets of printed sheets were sold to their first owners. Moreover, three of the selected pairs also exhibit distinctive typographic variations, belying the notion that they are ‘duplicates’. Here we offer only the briefest introductions to these pairs of books, which call out for further study and comparison:

Cicero, De Officiis. [Mainz:] Johann Fust & Peter Schoeffer, 4 February 1466.

Scheide 31.17

These two small folios, both printed on vellum, are from the second edition of Cicero’s treatise on the honorable fulfillment of moral duties, one of the first Classical works to be published. The Scheide copy, richly illuminated in Franco-Flemish style, is among the most beautiful of the roughly 50 copies that survive. It emerged from the collection of Ralph Willett (1719–1795), whose library at Merly was sold by Sotheby’s in 1813, and later was owned by Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex (1773–1843), and Robert Stayner Holford (1808–1892), of Gloucestershire, respectively. In 1925 Holford’s son sold the book to the Philadelphia bookseller A.S.W. Rosenbach, from whom Gertrude Scheide Caldwell purchased it as a Christmas gift for her brother John H. Scheide in December, 1927.

EXKA Incunabula 1466

Princeton’s other copy, decorated in German style, has been traced back to 1572, when ‘David Weisius’ was recorded as its donor to the town library of Augsburg. This individual was probably David Weiss (1531–1593), Augsburg patrician and town benefactor. It remained in Augsburg until 1798, after which it passed through three important private collections in Moscow.1 In 1931 the Soviet government sold it through Maggs Brothers, London, to Grenville Kane, whose collection came to Princeton University Library in 1946.

Recent research has led to the important discovery that the pair of painted coats-of-arms on the first page of Princeton’s Cicero refers to the German noble families of Truchseß zu Wetzhausen (left) and Wilhelmsdorf (right). To date, the only known union between these families was the mid-15th-century marriage of Jakob Truchseß zu Wetzhausen of Dachsbach and Susanna von Wilhelmsdorf.2 Their son, Dr Thomas Truchseß zu Wetzhausen (ca. 1460–1523), Dean of Speyer Cathedral, one-time student and later defender of Johannes Reuchlin, and correspondent and host of Erasmus of Rotterdam, was almost certainly the owner of Princeton’s 1466 Cicero.

Comparison of the Princeton and Scheide copies also reveals several typographic variants, including the presence in the Scheide copy of a four-line Latin incipit, printed in red on the first page, but omitted from the Princeton copy, in which a shorter titulus was written in by hand; numerous instances of each of these contingencies survive. Another striking difference is found on f. 14 verso, where the Scheide copy has the heading printed as usual in red type, while in the Princeton copy, the entire heading was printed upside down – an isolated accident that resulted from one of the many complications of printing with two colors.

St Augustine, De Civitate Dei. Rome: Conradus Sweynheym & Arnoldus Pannartz, in domo Petri de Maximo, 1468.

EXKA Incunabula 1468

This Royal folio is either the second or the third edition of this foundational text of Western Christendom, following the Subiaco edition of 1467 and possibly the Strasbourg edition, datable not after 1468. The first page of the text in the Princeton copy was illuminated in colorful Italian ‘bianchi girari’ style. Interestingly, for the gilt initial G that introduces the words ‘Gloriosissimam civitatem dei’, a woodcut stamp, not printed in other copies, provided black outlines for the illuminator’s work, which continued free-hand into the margin. Several pages bear extensive contemporary annotations. The volume was bound in the 1790s for the British bibliophile Michael Wodhull (1740–1816), and was acquired by Princeton in 1946 with the Kane collection.

Scheide 59.5

By contrast, the copy purchased by John Scheide in 1940, which emerged from the Syston Park Library in 1884 and was rebound in London by Douglas Cockerell in 1903, never received its requisite initials or decoration by hand; indeed, the book reveals virtually no evidence of use by early readers. The copy is nevertheless of considerable interest, as its introductory leaf bears a beautifully written and historically significant gift inscription (below), which records that Nicolò Sandonino (1422–1499), Bishop of Lucca beginning in 1479, presented this book to the Carmelites of San Pietro Cigoli in Lucca in 1491. It is curious that these friars, who disposed of numerous important books during the early 18th century, seem to have had no use for the bishop’s gift.

The Bishop of Lucca’s gift inscription, 1491.

Leonardo Bruni, De bello Italico adversus Gothos. Foligno: Emiliano Orfini & Johann Neumeister, 1470.

EXKA Incunabula 1470 Bruni

The first book printed in the small Italian town of Foligno was this history of the 5th-century Goth invasion of the Italian peninsula, compiled in 1441 by Leonardo Bruni. It was published in 1470 by Johannes Neumeister, a peripatetic printer from Mainz who made a career of enticing investors into supporting unsustainable printing ventures. It is bound with another rare Chancery folio, the only copy held in America of Bernardus Justinianus, Oratio habita apud Sixtum IV contra Turcos. [Rome]: Johannes Philippus de Lignamine, [after 2 Dec. 1471]. The rubrication throughout is French, and the bottom margin of the first leaf bears the inscription ‘Jacques le Chandelier, 1550’. This owner is probably to be identified with the contemporary Royal Secretary in Paris by that name. The volume later wandered through a series of distinguished European private libraries and came to Princeton University with the Kane collection in 1946.3

Scheide 40.1

The Scheide copy, illuminated in the Italian ‘bianchi girari’ (white vine) style, is probably the one offered by the Ulrico Hoepli firm in Milan in 1935. It subsequently entered the library of Giannalisa Feltrinelli (1903–1981), an Italian heiress and bibliophile who had homes in Rome, Milan, Geneva, and Stanbridge East, Canada. The book was auctioned at Christie’s in New York on 7 October 1997, lot 19, to H. P. Kraus. When his firm’s inventory was auctioned by Sotheby’s in New York in December 2003, the book remained available and was bought after the sale by William H. Scheide.

In addition to featuring contrasting French and Italian hand-decoration, the two copies are differentiated by variant typesetting in their colophons, which include different spellings of the surname and hometown of Neumeister’s patron, the master of the papal mint in Foligno, Emilianus de Orfinis. Whereas the colophon in Princeton’s copy reads ‘Ursinis Eulginas’, that of the Scheide copy has been corrected to ‘Orfinis Fulginas’ (below).

Ptolemy, Cosmographia. Ulm: Lienhart Holle, 16 July 1482.

The Super-Royal folio ‘Ulm Ptolemy’ of 1482 is famous for its 32 large woodcut maps, including the great double-page ‘World Map’ carved by Johannes Schnitzer of Arnsheim, 26 regional maps based on Ptolemy’s 2nd-century CE descriptions, and five new maps of Italy, France Spain, Scandinavia, and the Holy Land, based on manuscript projections by the editor of the work, Nicolaus Germanus, a Benedictine monk from the diocese of Breslau who lived and worked in Florence.

EXKA Ptolemy 1482

The Princeton copy, sold by the Rappaport firm in Rome toward the beginning of the last century, came with the Grenville Kane collection in 1946. The Scheide copy, richly hand-colored throughout, was inscribed in 1509 by Johannes Protzer (d. 1528), a scholar and bibliophile of Nördlingen, Germany. It emerged in the collection of Sir Thomas Phillipps in the 19th century and was acquired by John H. Scheide from A.S.W. Rosenbach in 1924.

Scheide 58.6

Although bibliographers sometimes discuss two 1482 Ulm ‘editions’ of this book, in fact there was only one edition, albeit one with many of its maps accompanied by textual descriptions that can appear in one of two or more alternate settings. For example, in the Princeton copy (below, left), the ninth map for Asia is accompanied by text that was composed into columns of 27 lines within a somewhat cramped square-shaped woodcut frame. By contrast, in the Scheide copy (below, right), the same page was composed more spaciously into 30 lines, fitting less tightly into a taller rectangular frame. To date, there has been no conclusive analysis of all the variant pages. Only a systematic comparison of multiple copies will provide a clearer understanding of the production of the 1482 Ulm Ptolemy.

What Could be Better?

Whereas traditional rare book librarianship tended to look upon the acquisition of ‘duplicates’ as undesirable or wasteful, given that precious funds could go toward adding texts that were not already represented in the collection, it is worth considering the special pedagogical and research value of comparing two copies from the same edition side by side. Experienced scholars as well as first-time students can appreciate that the two copies present distinct multiples of the original creation, each one preserving its own archeological record of survival and human intervention. Rubrication, illumination, binding, annotation, censorship, damage, repair, and other reflections of ownership and use offer fascinating traces of their disparate trajectories through history, revealing the many ways in which old books, as Milton observed, ‘are not absolutely dead things, but doe contain a potencie of life in them’.

Addendum:

Readers may be interested in the Morgan Library’s virtual tour by John McQuillen, “Why Three Gutenberg Bibles?”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cIteWBHSa00&fbclid=IwAR2615uiqBWL15HGX8kAnOykQfWUBshMmNUIv1CRI6fBlQ8IvZ6jzz-jbjk

Notes:

1 Count Aleksei Golowkin (d. 1811) of Moscow, whose gilt coat of arms appears on the front cover of the red-dyed goatskin binding; Alexandre Vlassoff (d. 1825), Imperial chamberlain in Moscow; Prince Michael Galitzin / Golitsyn (1804–1860), also in Moscow, with whose family it remained into the 20th century.

2 Johann Gottfried Biedermann, Geschlechtsregister der Reichsfrey unmittelbaren Ritterschaft Landes zu Franken Löblichen Orts Baunach (Bayreuth: Dietzel, 1747), table 197.

3 Early owners included Paul Girardot de Préfond (during the 1760s) in Paris; Pietro Antonio Bolongaro Crevenna (1735–1792) in Amsterdam; Michael Wodhull (1740–1816) in London; and William Horatio Crawford (1815–1888) at Lakelands in Cork, Ireland. In 1897 it was offered by the Quaritch firm (Catalogue 166, no. 770).

You must be logged in to post a comment.