By Morgan Kelly, Office of Communications

An increase in human-made carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could initiate a chain reaction between plants and microorganisms that would unsettle one of the largest carbon reservoirs on the planet — soil.

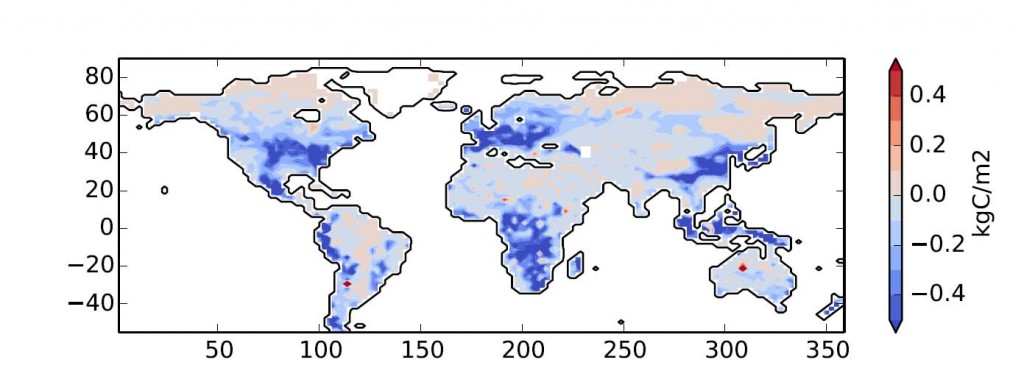

Researchers based at Princeton University report in the journal Nature Climate Change that the carbon in soil — which contains twice the amount of carbon in all plants and Earth’s atmosphere combined — could become increasingly volatile as people add more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, largely because of increased plant growth. The researchers developed the first computer model to show at a global scale the complex interaction between carbon, plants and soil, which includes numerous bacteria, fungi, minerals and carbon compounds that respond in complex ways to temperature, moisture and the carbon that plants contribute to soil.

Although a greenhouse gas and pollutant, carbon dioxide also supports plant growth. As trees and other vegetation flourish in a carbon dioxide-rich future, their roots could stimulate microbial activity in soil that in turn accelerates the decomposition of soil carbon and its release into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, the researchers found.

This effect counters current key projections regarding Earth’s future carbon cycle, particularly that greater plant growth could offset carbon dioxide emissions as flora take up more of the gas, said first author Benjamin Sulman, who conducted the modeling work as a postdoctoral researcher at the Princeton Environmental Institute.

“You should not count on getting more carbon storage in the soil just because tree growth is increasing,” said Sulman, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Indiana University.

On the other hand, microbial activity initiated by root growth could lock carbon onto mineral particles and protect it from decomposition, which would increase long-term storage of carbon in soils, the researchers report.

Whether carbon emissions from soil rise or fall, the researchers’ model depicts an intricate soil-carbon system that contrasts starkly with existing models that portray soil as a simple carbon repository, Sulman said. An oversimplified perception of the soil carbon cycle has left scientists with a glaring uncertainty as to whether soil would help mitigate future carbon dioxide levels — or make them worse, Sulman said.

“The goal was to take that very simple model and add some of the most important missing processes,” Sulman said. “The main interactions between roots and soil are important and shouldn’t be ignored. Root growth and activity are such important drivers of what goes on in the soil, and knowing what the roots are doing could be an important part of understanding what the soil will be doing.”

The researchers’ soil-carbon cycle model has been integrated into the global land model used for climate simulations by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) located on Princeton’s Forrestal Campus.

Benjamin N. Sulman, Richard P. Phillips, A. Christopher Oishi, Elena Shevliakova, and Stephen W. Pacala. 2014. Microbe-driven turnover offsets mineral-mediated storage of soil carbon under elevated CO2. Nature Climate Change. Article published in December 2014 print edition. DOI: 10.1038/nclimate2436

The work was supported by grants from NOAA (grant no. NA08OAR4320752); the U.S. Department of Agriculture (grant no. 2011-67003-30373); and Princeton’s Carbon Mitigation Initiative sponsored by BP.

You must be logged in to post a comment.