By Raphael Rosen, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Rotation is key to the performance of salad spinners, toy tops, and centrifuges, but recent research suggests a way to harness rotation for the future of mankind’s energy supply. In papers published in Physics of Plasmas in May and Physical Review Letters this month, Timothy Stoltzfus-Dueck, a physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), demonstrated a novel method that scientists can use to manipulate the intrinsic – or self-generated – rotation of hot, charged plasma gas within fusion facilities called tokamaks. This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Such a method could prove important for future facilities like ITER, the huge international tokamak under construction in France that will demonstrate the feasibility of fusion as a source of energy for generating electricity. ITER’s massive size will make it difficult for the facility to provide sufficient rotation through external means.

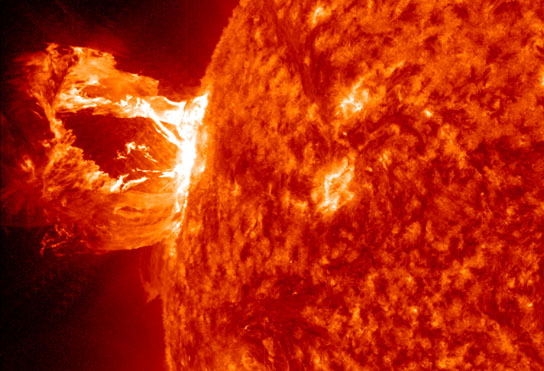

Rotation is essential to the performance of all tokamaks. Rotation can stabilize instabilities in plasma, and sheared rotation – the difference in velocities between two bands of rotating plasma – can suppress plasma turbulence, making it possible to maintain the gas’s high temperature with less power and reduced operating costs.

Today’s tokamaks produce rotation mainly by heating the plasma with neutral beams, which cause it to spin. In intrinsic rotation, however, rotating particles that leak from the edge of the plasma accelerate the plasma in the opposite direction, just as the expulsion of propellant drives a rocket forward.

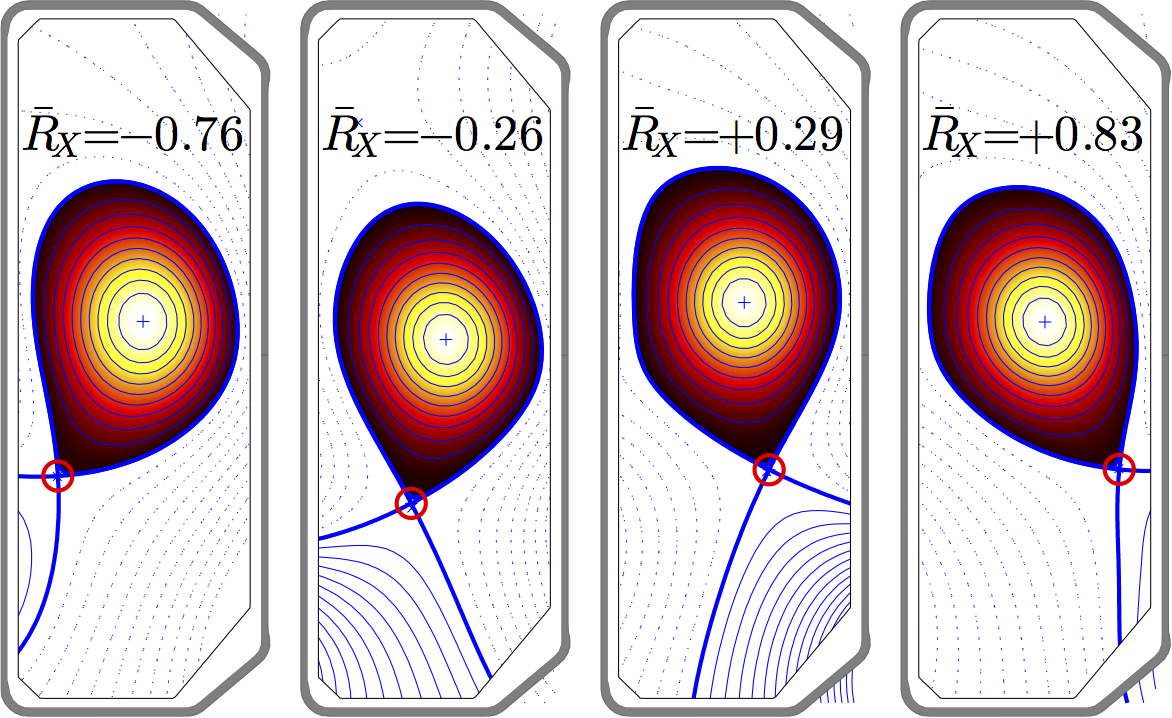

Stoltzfus-Dueck and his team influenced intrinsic rotation by moving the so-called X-point – the dividing point between magnetically confined plasma and plasma that has leaked from confinement – on the Tokamak à Configuration Variable (TCV) in Lausanne, Switzerland. The experiments marked the first time that researchers had moved the X-point horizontally to study plasma rotation. The results confirmed calculations that Stoltzfus-Dueck had published in a 2012 paper showing that moving the X-point would cause the confined plasma to either halt its intrinsic rotation or begin rotating in the opposite direction. “The edge rotation behaved just as the theory predicted,” said Stoltzfus-Dueck.

A surprise also lay in store: Moving the X-point not only altered the edge rotation, but modified rotation within the superhot core of the plasma where fusion reactions occur. The results indicate that scientists can use the X-point as a “control knob” to adjust the inner workings of fusion plasmas, much like changing the settings on iTunes or a stereo lets one explore the behavior of music. This discovery gives fusion researchers a tool to access different intrinsic rotation profiles and learn more about intrinsic rotation itself and its effect on confinement.

The overall findings provided a “perfect example of a success story for theory-experiment collaboration,” said Olivier Sauter, senior scientist at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and co-author of the paper.

Along with the practical applications of his research, Stoltzfus-Dueck enjoys the purely intellectual aspect of his work. “It’s just interesting,” he said. “Why do plasmas rotate in the way they do? It’s a puzzle.”

PPPL, on Princeton University’s Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas — ultra-hot, charged gases — and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. Results of PPPL research have ranged from a portable nuclear materials detector for anti-terrorist use to universally employed computer codes for analyzing and predicting the outcome of fusion experiments. The Laboratory is managed by the University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the largest single supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Stoltzfus-Dueck, A. N. Karpushov, O. Sauter, B. P. Duval, B. Labit, H. Reimerdes, W. A. J. Vijvers, the TCV Team, and Y. Camenen. “X-Point-Position-Dependent Intrinsic Toroidal Rotation in the Edge of the TCV Tokamak.” Physical Review Letters 114, 245001 – Published 17 June 2015.

![Schematic for cobalt-catalyzed [2pi+2pi] reaction.](https://blogs.princeton.edu/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/56/2015/06/2015_06_09_Chirik.png)

You must be logged in to post a comment.