By Diana Udel, University of Miami

Terrestrial rainfall in the subtropics — including the southeastern United States — may not decline in response to increased greenhouse gases as much as it could over oceans, according to a study from Princeton University and the University of Miami (UM). The study challenges previous projections of how dry subtropical regions could become in the future, and it suggests that the impact of decreased rainfall on people living in these regions could be less severe than initially thought.

“The lack of rainfall decline over subtropical land is caused by the fact that land will warm much faster than the ocean in the future — a mechanism that has been overlooked in previous studies about subtropical precipitation change,” said first author Jie He, a postdoctoral research associate in Princeton’s Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences who works at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory located on Princeton’s Forrestal Campus.

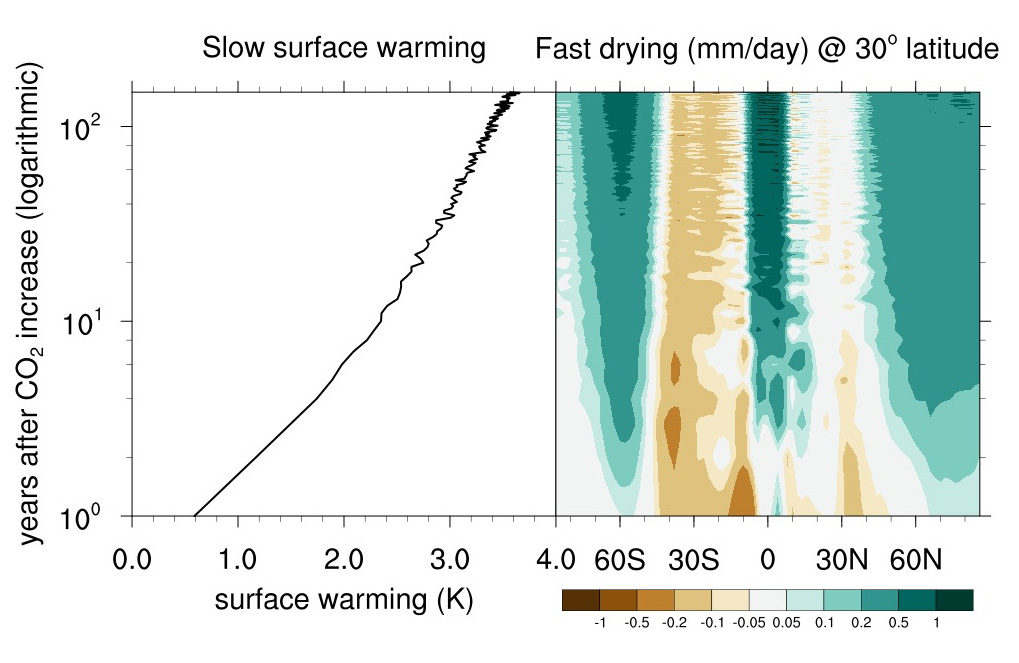

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, He and co-author Brian Soden, a UM professor of atmospheric sciences, used an ensemble of climate models to show that rainfall decreases occur faster than global warming, and therefore another mechanism must be at play. They found that direct heating from increasing greenhouse gases is causing the land to warm faster than the ocean. The associated changes in atmospheric circulation are thus driving rainfall decline over the oceans rather than land.

Subtropical rainfall changes have been previously attributed to two mechanisms related to global warming: greater moisture content in air that is transported away from the subtropics, and a pole-ward shift in air circulation. While both mechanisms are present, this study shows that neither one is responsible for a decline in rainfall.

“It has been long accepted that climate models project a large-scale rainfall decline in the future over the subtropics. Since most of the subtropical regions are already suffering from rainfall scarcity, the possibility of future rainfall decline is of great concern,” Soden said. “However, most of this decline occurs over subtropical oceans, not land, due to changes in the atmospheric circulation induced by the more rapid warming of land than ocean.”

Most of the reduction in subtropical rainfall occurs instantaneously with an increase of greenhouse gases, independent of the warming of the Earth’s surface, which occurs much more slowly. According to the authors, this indicates that emission reductions would immediately mitigate subtropical rainfall decline, even though the surface will continue to warm for a long time.

He is supported by the Visiting Scientist Program at the department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, Princeton University.

Read the abstract:

The study, “A re-examination of the projected subtropical precipitation decline,” was published in the Nov. 14 issue of the journal Nature Climate Change.

You must be logged in to post a comment.