By: Tien Nguyen, Department of Chemistry

Theoretical chemists at Princeton University have pioneered a strategy for modeling quantum friction, or how a particle’s environment drags on it, a vexing problem in quantum mechanics since the birth of the field. The study was published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

“It was truly a most challenging research project in terms of technical details and the need to draw upon new ideas,” said Denys Bondar, a research scholar in the Rabitz lab and corresponding author on the work.

Quantum friction may operate at the smallest scale, but its consequences can be observed in everyday life. For example, when fluorescent molecules are excited by light, it’s because of quantum friction that the atoms are returned to rest, releasing photons that we see as fluorescence. Realistically modeling this phenomenon has stumped scientists for almost a century and recently has gained even more attention due to its relevance to quantum computing.

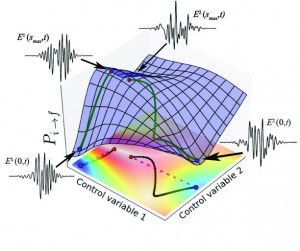

“The reason why this problem couldn’t be solved is that everyone was looking at it through a certain lens,” Bondar said. Previous models attempted to describe quantum friction by considering the quantum system as interacting with a surrounding, larger system. This larger system presents an impossible amount of calculations, so in order to simplify the equations to the pertinent interactions, scientists introduced numerous approximations.

These approximations led to numerous different models that could each only satisfy one or the other of two critical requirements. In particular, they could either produce useful observations about the system, or they could obey the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which states that there is a fundamental limit to the precision with which a particle’s position and momentum can be simultaneous measured. Even famed physicist Werner Heisenberg’s attempt to derive an equation for quantum friction was incompatible with his own uncertainty principle.

The researchers’ approach, called operational dynamic modeling (ODM) and introduced in 2012 by the Rabitz group, led to the first model for quantum friction to satisfy both demands. “To succeed with the problem, we had to literally rethink the physics involved, not merely mathematically but conceptually,” Bondar said.

Bondar and his colleagues focused on the two ultimate requirements for their model – that it should obey the Heisenberg principle and produce real observations – and worked backwards to create the proper model.

“Rather than starting with approximations, Denys and the team built in the proper physics in the beginning,” said Herschel Rabitz, the Charles Phelps Smyth ’16 *17 Professor of Chemistry and co-author on the paper. “The model is built on physical and mathematical truisms that must hold. This distinct approach creates a new rigorous and practical formulation for quantum friction,” he said.

The research team included research scholar Renan Cabrera and Ph.D. student Andre Campos as well as Shaul Mukamel, professor of chemistry at the University of California, Irvine.

Their model opens a way forward to understand not only quantum friction but other dissipative phenomena as well. The researchers are interested in exploring the means to manipulate these forces to their advantage. Other theorists are rapidly taking up the new paradigm of operational dynamic modeling, Rabitz said.

Reflecting on how they arrived at such a novel approach, Bondar recalled the unique circumstances under which he first started working on this problem. After he received the offer to work at Princeton, Bondar spent four months awaiting a US work visa (he is a citizen of the Ukraine) and pondering fundamental physics questions. It was during this time that he first thought of this strategy. “The idea was born out of bureaucracy, but it seems to be holding up,” Bondar said.

Read the full article here:

Bondar, D. I.; Cabrera, R.; Campos, A.; Mukamel, S.; Rabitz, H. A. “Wigner-Lindblad Equations for Quantum Friction.” J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1632.

This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation CHE 1058644, the US Department of Energy DE-FG02-02ER-15344, and ARO-MURI W911NF-11-1-0268.

![[2Fe–2S] cluster in front of a leaf. (Image by C. Todd Reichart)](https://blogs.princeton.edu/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/56/2014/11/2014_11_21_Chan-625x468.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.