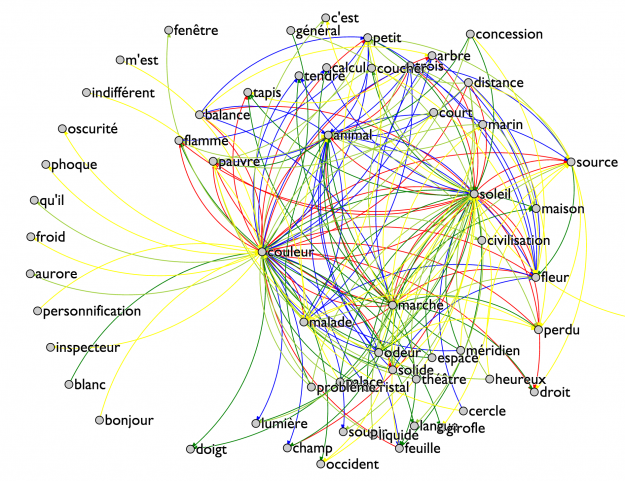

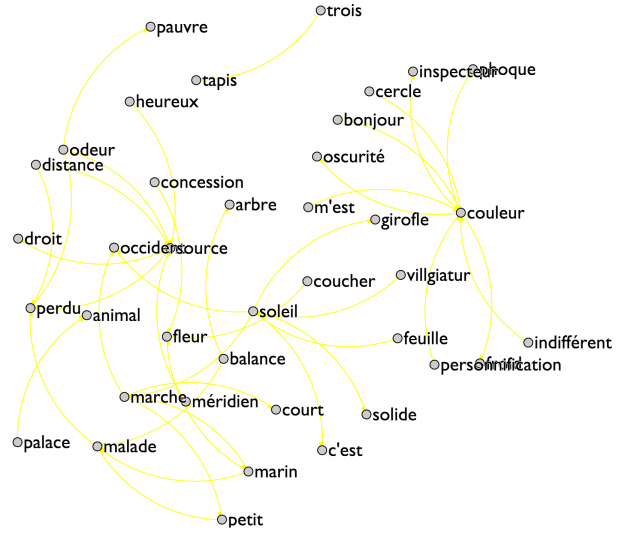

Figure 1: All often encountered connections within Les Champs Magnétiques by Andre Breton and Philippe Soupault. The different colored Red, Blue, Green, Olive and Yellow lines show how often pairs of words are encountered, red indicating the most encountered pairs and yellow indicating the least encountered pairs. Explore the interactive version.

Introduction

When the industrial revolution rapidly took form in Western Europe at the beginning of a new century, the term “automatism” suffered a semantic shift in psychology, as David Lomas argued in The Haunted Self. It initially expressed a mechanistic undercurrent, relying on the Freudian idea of reflexive, basic mental faculties overtaking higher level cognition processes, but “automatism” became a description of the spontaneous, undirected thought process – whether that be of words or of mental images. It is this kind of thought process that the Surrealists attempted to bring forth, as a trace of the unconscious, an unexplored part of the human mind to which they assigned equal importance as the conscious side.

By performing a statistical analysis of the Surrealists’ automatic texts, we endeavored to capture and interpret the state of mind represented in the automatic texts. Specifically, by unveiling hidden connections within automatic texts, we performed an analysis that combined Freudian and Surrealist elements which revealed patterns within the unconscious side of the authors’ minds. By detecting such patterns, we also attempted to liberate the automatic text of its grammatical restrictions that, for the Surrealists, would have been ideally dispensed of to truly free the mind. The illustrations we created to reveal the hidden connections within automatic writing can be seen as artistic works by themselves, in which we separate and liberate the unconscious thoughts of the authors from their grammatical limitations.

Freud

In order to analyze the Surrealists’ understanding of the mind in a holistic way, we referred to the earliest theory of psychoanalysis developed by Sigmund Freud, which had a significant influence on the surrealist concept of self-exploration. As the surrealist movement began, the Surrealists were heavily influenced by Sigmund Freud’s work on dreams and psychoanalysis, and its relation to the unconscious. In his works, The Interpretation of Dreams and On Dreams, Freud asserts the importance of the dream as an instrument to access glimpses of the inner human psyche. Recognizing traces of psychological conditions such as phobia and dread embedded in dreams, Freud created the theory of psychoanalysis, differentiating between the conscious and the unconscious mind, where repressed experiences reside, pulsating through slices of dreams in attempts to reach consciousness. Furthermore, he divides general unconscious thoughts into two subsets: “preconscious” ideas, which are latent, but may emerge into the conscious side, and “unconscious” ideas, which are repressed and cannot surface to the rational thought without the help of psychoanalysis. These concepts are also explored in The Ego and the Id, where he splits the human mind into the inner id, super ego, and ego. The id is the unorganized part of our mind that includes our most basic, instinctual drives. The super ego is the internalization of society’s cultural rules and thus plays the moralizing role in the mind. Lastly, the ego is the realistic, mediating principle, which strives to please the id’s drive, but in appropriate and pragmatic ways. Moreover, he believes productive human societal existence is only feasible with the renunciation of the id. Management of the id is essential in the development of man’s higher mental activities in order to obtain intellectual, scientific, and aesthetic achievements. Interpreting dreams was essential to Freud’s research of the human psyche. Consequently, he utilized his interpretation and psychoanalytic models of dreaming in order to gain understanding of the quelled unconscious of individuals. Through such findings, he believed he could clarify the origins of individuals’ “neuroses” and develop cures.

Freud describes his new method, psychoanalysis, in On Dreams. The patient would first concentrate on an idea or a dread. Then, he or she would verbalize any rising impression from focusing on the idea and allow these new rising thoughts to spill out of the mind by verbalizing them. Freud concedes that the impressions may seem nonsensical at first, but this flow of thought will ultimately lead to a discovery of the source of the dread. Interestingly, Freud then notes that this method can be practiced alone, which would be most effectively accomplished by writing down every thought on paper, which doubtlessly reminds us of the Surrealists’ automatic writing.

Freud used this psychoanalytical method on dreams in a similar way. He would divide the dream into various parts, then instruct his patients to concentrate separately on each part, so that they could experience each section independently of the others. Upon experiencing each independently, the patient could then express their various impressions and associations. Moreover, connections between the patient’s conscious life and the dream state would be uncovered. Thus, Freud concluded that there was a clear logic behind dreams, which by itself seemed “passionless, disconnected, and unintelligible,” but was made meaningful through psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis revealed that dreams weren’t all that nonsensical, but rather simply needed to be deciphered in relation to the conscious life, revealing deeper desires that are typically stifled.

As Breton encountered short excerpts of Freud’s work, he began to express interest in Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, which he then shared with other members of the surrealist movement. His major ideas were highly influential in the development of surrealism, widely applied later on in the study of the unconscious. Breton was so fascinated by Freud’s work, that he actually visited Freud in Vienna in 1921 in hopes of developing Freud’s concepts–particularly those in The Interpretation of Dreams–through surrealism; however, the meeting ended with little success, as Freud appeared detached and relatively uninterested. Breton’s continual efforts to interact with Freud–to no avail–suggest he was seeking approval of his actions, and of the surrealist movement in general. Breton never truly received this approval nor gained any positive reinforcement from Freud as evident from what Freud says in his letter to Breton: “Although I have received many testimonies of the interest that you and your friends show in my research… I am not able to clarify for myself what Surrealism is and what it wants… perhaps I am not destined to understand it, I who am so distant from art.” Thus, by the end of their interactions and discussions, it became clear that although the Surrealists and Freud shared an interest in exploring the depths of the human psyche, their views differed in their application of this information.

Although the Surrealists appropriated certain Freudian concepts, particularly that of the id, they differed in their interpretation of his findings. In his first Surrealist Manifesto, Breton states that the goal of Surrealism is to “solve the problems of the world,” which was actually rather similar to Freud’s goal of enabling humans to live efficiently as Freud believes the liberation of the id poses a “problem of the world.” This was where their interpretations differ: what Freud saw as the problem, the Surrealists believed to be the solution. Surrealists took an opposite approach to Freud because rather than seeking to quell the instinctual desires of the unconscious, they looked towards it to unlock the secrets of the material world. The Surrealists strived for authenticity, which they primarily thought could be discovered via the unconscious. They believed that the unconscious activity (which could be accessed through dreams) represented the space between authentic materiality and the soul’s essence. Thus they appropriated Freud’s theory of the id, ego, and superego, but rather than using this information to discover cures to “neuroses,” they examined his work through a philosophical lens.

According to David Lomas, the rather new approach to the unconscious that Surrealists attempted through automatic writing held “the promise of a certain plenitude which is foreign to a Freudian conception of the unconscious.” Lomas suggests here that automatic writing has the ability to access the unconscious to a degree beyond what Freud sees as attainable. The Surrealists defined the unconscious state as a reachable state, while Max Ernst believed it to be a latent or hidden consciousness. In contrast, Freud claims that the unconscious should not be confused with or pictured as a second consciousness, but instead has unique, specific properties, irreducible to those of conscious thought, being unknowable in itself. These different ideas of the unconscious made us wonder whether the Surrealists actually defined the “unconscious” as an intermediary state of mind, accessible in a semi-conscious state, but exhibiting a type of randomness and novel associations foreign to consciousness. This is one of the questions we explored in our project, by finding the most common associations of words in Les Champs Magnétiques and interpreting the nature of the associations, comparing them to other common associations that use the same or similar words.

To this end, we analyzed one of the Surrealists’ first and foremost methods of automatism to reach the unconscious in an attempt to change the way they perceive the world. Automatism directly relates to Freud’s methods of interpreting dreams because they both seek to reach an understanding of the unconscious. Breton’s first definition of “surrealism” in Manifeste du Surréalisme was actually “psychic automatism in its pure state.” Automatism is described as a process in which one completely clears his mind and puts oneself in a trance-like state, letting out, verbally or through writing, whatever emerges in the mind, so that no thought is stifled or censored. The mind becomes liberated in its purest form without the barriers that have been built by society’s indoctrinations. Therefore, each individual involved simply becomes the objective recording device of the mind. One of the most famous examples of the Surrealists’ attempts at automatic writing is André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s Les Champs Magnétiques (1920), which we used as data for our experiments and explorations.

Our specific purpose in this project was to analyze the Surrealists’ usage of automatic writing as a means to obtaining a more genuine human experience. Through our findings, we drew parallels between the surrealist practices and various theories of the mind, while also analyzing surrealist practices of automatism from a quantitative point of view. We thus made inferences regarding the surrealists practices themselves and questioned how automatic writing influenced the minds of the Surrealists employing the exercise.

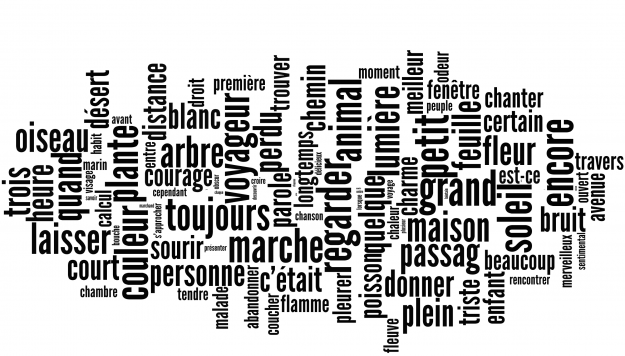

Figure 2: Most frequent words encountered within “Les Champs Magnétiques” by Andre Breton and Philippe Soupault. The greater the size of the word, the more times it has been encountered.

Experiment

We came up with an experiment, which offers insight in patterns of thought that automatic writing creates, in an attempt to characterize and interpret the states of mind emerging from automatic writing. Using the original automatic texts written by Breton and Soupault, we found the most frequent meaningful words (not including articles, prepositions, exclamations, etc.) and the most frequent associations of words within a sentence. Our digital analysis thus reveals hidden patterns within automatic writing, which gave us access to a new interpretation of the mental state of the surrealist writers. Such a large-scale digital analysis created a unique opportunity to compare patterns within automatic writing with characteristics of the unconscious, which Freud describes in The Interpretation Of Dreams. Through text analysis, we empirically interpreted the mental state that the Surrealists experienced during the automatic process, with the help of a Freudian analysis that encapsulates his methods from psychoanalysis of interpreting the glimpses of the unconscious. Although our experiment and analysis mirrors certain Freudian procedures and methodologies, our analysis was also nuanced by specific surrealist beliefs, such as the surrealist image, meaning the collision of two seemingly opposite concepts (or words) that create completely new meanings. We combined two seemingly different beliefs and practices (of Freud and the Surrealists) in order to create our own interpretation of the tension between their different ideas, just as Breton developed the surrealistic idea of the creative potential of the juxtaposition of two different realities (conscious and unconscious).

Methods

We used the scanned PDF version of Les Champs Magnétiques by Andre Breton and Philippe Soupault, and transformed it into a simple editable text by using the ABBYY Fine Reader program from the digital humanities library. This was necessary because the programs that are available so far for processing text must be able to access the words inside a document, a process invalid with a PDF document. We used the original version of the document, in French, in order to preserve the authenticity of words and expressions. Then, with the help of the digital humanities staff, we wrote a program in Python, using the Natural Language Toolkit, which first reduced each word to its root (so that “cat” and “cats”, for example, would refer to the same object), then eliminated the words that contained less than four letters in order to remove the prepositions and meaningless words that would appear many times in the text in order to facilitate its grammatical and syntactical correctness. At this point, we counted the most frequent words and associations of words in the text. We created two images that help visualize the most frequent words, in order to understand the category that most of these words belong to, and their meaning in relation to the scope of Les Champs Magnétiques.

This idea of word associations stems from Freud’s method of analyzing the thought process, “we obtain matter enough for the resolution of every morbid idea if we especially direct our attention to the unbidden associations which disturb our thoughts – those which are otherwise put aside by the critic as worthless refuse”. We were also influenced by Breton’s statement in his Manifeste du Surréalisme: “… from the fortuitous juxtaposition of the two terms that a particular light has sprung, the light of the image, to which we are infinitely sensitive”. In this quotation, Breton discusses the importance of juxtaposing two terms in order to analyze the tension that exists between them. By observing which words appear most frequently and the associations between them, we were able to interpret, as Breton and Surrealists alike did, the tension that is created between the various words and concepts. We decided to associate the words that appear together in the same sentence, rather than in the same paragraph, since there is great variation in topics within each paragraph. In the interactive visualization, we took the first two hundred most frequent pairs of words, and split them into five categories: the first one includes the first fifty most frequent word associations, the second one contains the next fifty most frequent words associations, and so on. Thus, we accorded hierarchical importance to groups of associations with close frequency, rather than just differentiating between frequencies, as it may not matter whether an association is the most frequent or the second most frequent, as long as it is in the top. We analyzed the results by looking at the type of associations found, their randomness, the category of words (semantic and as a part of speech), and their relation to the most frequent words found in the previous simulation.

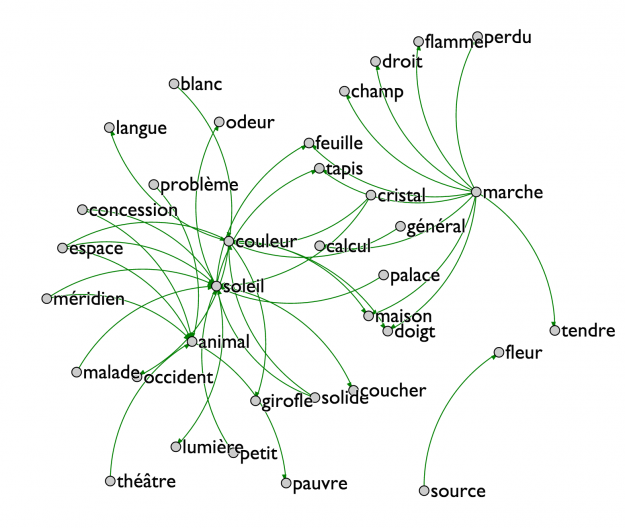

Figure 3: Most often encountered pairs of words in “Les Champs Magnétiques”. Explore the interactive version.

Interpretation

Further on, we attempted to build an interpretation by analyzing different words associations and most frequent words in not only a Freudian, but also surrealist manner, as we explained before. After discovering different patterns, we began to analyze the inner self as exhibited in the unconscious and the individual’s inner emotions and expressions. Thus, within the automatic, surrealist text of Les Champs Magnétiques, we have discovered certain surrealist tendencies, encapsulated by three main categories of words: nature, abstract concepts, and human actions and creations. In our opinion, these words are used unconsciously to build an abstract representation of the self, departing from rationality and from the increasingly mechanistic and repressive urban life, towards a setting juxtaposed with nature. This is particularly interesting, since the surrealist movement had an intrinsically urban component, as observed in Brassaï’s photographies, in Louis Aragon’s Le Paysan de Paris, in Andre Breton’s Nadja, and many other surrealist creations. To this end, we may nuance our interpretation of the duality between the urban setting and nature, relating the mechanistic setting to the development of science that led to an overwhelming intrusion of technology in the French society of the 19th century. We can infer a tension between the technical advances that take over the everyday life (such as the mass-produced objects), and the natural world, as an escape towards a more individualized, meaningful way of living. Accordingly, we observed characteristics of the inner self exhibited in the unconscious: repression due to the industrialization of society, desire to escape towards an opposite world, identified with the world of nature, and frustration due to the constraints of the language to express fully the Surrealists’ states of mind and revelations.

Words found in association:

| Association | Words |

| Human | langue, tapis, marcher, malade, pauvre, trois, marin |

| Nature | soleil, animal, flamme, arbre, champ, coucher, fleur, espace, froid, lumière, feuille, aurore, |

| Abstract concepts | couleur, lumière, distance, langue, cercle, champ, problème, obscurité |

The inner self plays a very important part in surrealist endeavors, as the process of introspection is viewed as one of self-development, a path to a better life, as in Le Paysan de Paris, by Louis Aragon. In this automatic text, we argue that the glimpses of the unconscious exhibited through automatic writing build towards an abstract representation of the inner self.

One category that we have recognized is the common occurrence of words associated with human life and activity. These words include langue, tapis, marcher, malade, pauvre, trois, and marin. Marcher has dual meanings, either the human action of walking, or the more mechanistic definition, to function, but in the text, it is used only to mean walking. The words that it is connected to are varied, from nature words such as soleil (sun) and animal to more negatively connoted words such as malade (sick/disease) and perdu (lost). The connections to nature can emphasize the move to nature. The more negative associations, in addition to another commonly occurring human state of being that we found, pauvre (poor) possibly connote more negative ideas of current society and hint at the idea of a repressed human state of being. Tapis is used in the text in different forms, tapis (carpet), tapisserie (tapestry), and tapissier (upholsterer). Tapis and tapisserie are both human constructs that tend to be elaborately made, and in the context that these words are found in, these are often in association with nature images such as this: “les tapisseries du ciel de Juin et des hautes mers,” translating to “the tapestries of June skies and high seas” (Eclipses). The usage of an elaborate human construction to describe something natural isn’t uncommon in literature, but is still worth noting in the surrealist context.

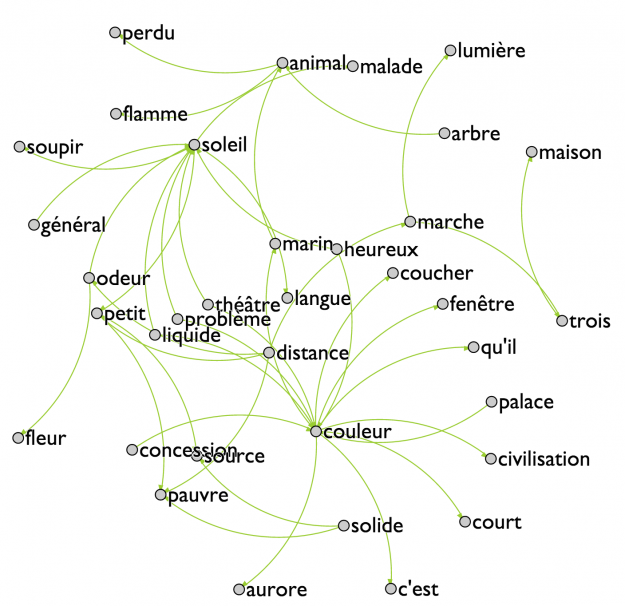

Figure 4: Second most encountered set of pairs of words in “Les Champs Magnétiques”. Explore the interactive version.

The Surrealists had a tendency to place typical human constructs (tapestries) in completely natural contexts (skies and seas), as seen in many paintings by Salvador Dali, and in some of their movies, such as Un Chien Andalou, by Louis Buñuel. Furthermore, tapis can also be recognized as a textile that is woven; perhaps, “textile” is a stand-in for “texte.” This could reflect the nature of all the unconscious written down in text, revealing the interwoven complicated meanings and undertones. In the text, tapissier is used along with another commonly used word, marin (sailor), and both are notably seen as feeling nostalgic. A tapissier has dual meanings, one simply meaning upholsterer, which can create bourgeois and materialistic connotations since his/her job is to decorate homes, but either Soupault or Breton (whoever wrote the section titled Ne Bougeons Plus) placed it in a hopeless and even seemingly dystopian context, where “the nocturnes of dead musicians lull the cities sunk in endless slumber”, possibly adding to their general rejection of bourgeois and romanticized ideas (Ne Bougeons Plus). The second meaning of tapissier is writer, which can be interpreted so that the automatic writer is unconsciously reflexive of the actual action of automatic writing, while simultaneously, projecting an abstract representation of itself through the unconscious. Marin also shows up very often in the text. A marin is one who travels the world, often in search of something, perhaps hinting at the surrealist goal to attempt to try to find meaning in life and make their lives more interesting. Trois (three) is a number that appears remarkably often in the text, which is interesting because it is also often a special number in other contexts such as religion and mythology, causing us to consider the inherent connections between surrealism and other prevalent forms of thought. We can also interpret trois in another way, directly relevant to the text in that the most common words in the text belong to three categories: human characteristics or creations, abstract concepts, and nature elements. From this, it is possible to infer that the unconscious might exhibit an understanding of the types of concepts it expresses, and conveyed through the repetition of the number three throughout the text.

Figure 5: Third most encountered set of pairs of words in “Les Champs Magnétiques”. Explore the interactive version.

Another category of words found in most frequent association is abstract concepts, such as couleur, distance, perdu, and champ(s). We classify them as such due to the fact that they represent abstract qualities of objects, defined by humans, but that do not have their own representations in the real world. These are connected in our text to human (or animal) characteristics or creations, such as marcher and malade – connections that reduce characteristics of the self to abstract concepts, weaving a representation of the self in the unconscious mind.

Through analysis of the common words and word associations, we believe the subconscious of the Surrealists’ express an interest in the tension that arises from the interaction of nature with the scientific world of the machine (and automatism). The Surrealists hoped to further immerse themselves in nature, both in practice (through liberating themselves from societal rules and regulations) and in space – while simultaneously juxtaposing this experience with their scientific concepts. The words related to nature that appear over and over again in Les Champs Magnétiques are: animal, flamme, fleur, champ, feuille, soleil, and arbre. These words are not only often associated with nature elements (such as animal and soleil, arbre and fleur), but also connected to humans and science. For example, the association of calcul with soleil and pauvre with animal. We also noticed various areas where certain words typically associated with nature actually had dual meanings, which juxtaposed the connection between nature and humans. One example is the word champ, meaning field in English. The word champ conjures up various concepts: a scientific meaning, where the field is meant to represent the forces of nature, a mathematical meaning, in which the field organizes logical sets and opposing this, a very rational and organized field of crops disrupting the natural growth of plants. The Surrealists clearly had an impassioned interest in duality and contradictions within concepts and words. Their interest realistically stems from a desire to place themselves in an inbetween state of surreality, which is defined as between two different realities: our conscious and unconscious existence. In the example above, the Surrealists utilize the word champ in a way where they get to experience both the rational and irrational side of it. Another word embedded with duality commonly used in Les Champs Magnétiques is feuille, which can mean either leaf, but also a sheet of paper, which is a human invention, used as a medium for writing. Here, again the Surrealists seem to be fascinated by the duality of language and attempt to utilize the word in both its natural setting, but also in the setting we, as humans, have created for it. In doing so, the Surrealists achieve for themselves a state of surreality where both can exist side by side, creating a spark from their tensions that Breton describes in Manifeste du Surréalisme.

In this journey towards nature we found other associations of words that speak to central surrealist conceptions. For example, the connection between soleil (an element of nature), and malade, which in this context refers to the human ailments of the mind show the Surrealists’ praising of different ways of perceiving the world that were disregarded by society as malfunctions. This viewed can be argued by looking at L’Immaculée Conception, where Breton and Eluard simulate different mental ailments, attempting to extend the possibilities of mental perception. Mental illnesses were a key concept in the surrealist era, as we argued before, since the Surrealists artists viewed them as gateways to novel, revelatory states of mind, which break the limits of the human thought process that had been constrained by artificial definitions of normality in a rational society. To this end, the Surrealists explored and even imitated different mental conditions in an attempt to reach superior states of mind and to access more genuine ways of living. On the other hand, soleil (sun), may be related to the idea of light (which is also a frequently occurring word in the text), which is a key metaphor in Manifeste du Surrealisme. Breton speaks of the “spark” that is created when two images of different nature come together, as a metaphor for the revelatory potential that unconventional perceptions of the world may have. The “spark”, closely related to the physical construction of a circuit that emulates the human thought process, comes as a new purpose to be achieved in order to attain a more genuine way of thinking and of living. “Sun” comes in close connection with “light” and “spark”, and may represent the superior state of mind that the Surrealists associated with different mental illnesses. It is interesting to have found exactly this association exhibited by a non-conscious state of mind in which the automatic texts were written, re-confirming an unconscious desire to depart from normality and to find salvation in a new lifestyle.

Figure 6: Fourth most encountered set of pairs of words in “Les Champs Magnétiques”. Explore the interactive version.

Conclusion and future directions

This new meaning of Breton’s automatic writing becomes visible only in the absence of the grammatical rules which constrained him from fully capturing his unconscious state. What can be seen throughout Figure 1-7 is a new form of art that emerges from Les Champs Magnétiques which, we believe, captures the essence of Breton and Soupault’s mental state and reveals the primal desire of the Surrealists to juxtapose nature with its opposite counterparts, the mechanic and industrial society. We may interpret the nature-related elements as a representation of a liberated state of mind, free from the mechanical constrictions that their surroundings impose them. Such a duality may be considered a form of resistance to the fast-paced industrialization process from the beginning of the twentieth century. While our analysis provides insights into Breton and Soupault’s individual mental states, what remains to be done is to understand the collective unconscious hidden within all automatic texts. By analyzing whole collections of automatic texts we thus hope to dive deeper into the Surrealists’ collective automatic psyche and understand what drove not only Breton and Soupault towards the natural world, but also the whole surrealist movement.

Figure 7: Fifth most encountered set of pairs of words in “Les Champs Magnétiques”. Explore the interactive version.

Bibliography

[1] Lomas, David. The Haunted Self. Yale University Press. 2001.

[2] Breton, Andre. Maniféste du Surrealisme. Figaro. 1924.

[3] Freud, Sigmund. On Dreams. 1901.

[4] Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Franz Deuticke. 1899.

[5] Freud, Sigmund. The Ego and the Id. Internationaler Psycho- analytischer Verlag (Vienna), W. W. Norton & Company. 1923.

[6] Aragon, Louis. Paris Peasant. Translation from French by Simon Watson Taylor. Exact Change. 2004.

[7] Breton, Andre and Eluard, Paul. L’Immaculée Conception. Serpent’s Tail. 1992.

[8] Breton, Andre. Communicating Vessels. 1932.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Proffesor Rentzou for all her guidance during the semester and for providing great insights in the surrealist world. We also really appreciate the patience that Lindsey during all our invaluable discussions.

Last, but not least, we owe many thanks to Cliff and Natasha, who helped us with the realization of the experiment, guiding us in using computer tools from the Digital Humanities Center.