By Tien Nguyen, Department of Chemistry

A new method for labeling molecules with radioactive elements could let chemists more easily track how drugs under development are metabolized in the body.

Chemists consider thousands of compounds in the search for a new drug, and a candidate’s metabolism is a key factor that must be evaluated carefully and quickly. Researchers at Princeton University and pharmaceutical company Merck & Co., Inc. report in the journal Nature that scientists can selectively replace hydrogen atoms in molecules with tritium atoms — a radioactive form of hydrogen that possesses two extra neutrons — to “radiolabel” compounds. This technique can be done in a single step while preserving the biological properties of the parent compound.

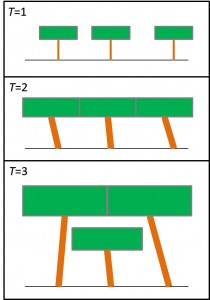

While current state-of-the-art techniques are quite reliable, they only work when dissolved in specific solvents, ones that aren’t always capable of dissolving the drug compound of interest. The researchers’ method, however, used an iron-based catalyst that is tolerant to a wider variety of solvents, and it labels the molecules at the opposite positions as compared to existing methods.

“The fact that you can access other positions is what makes this reaction really special,” said corresponding author Paul Chirik, the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Chemistry at Princeton. Previous methods only incorporate radioactive tritium atoms into the molecule directly next to an atom or a group of atoms called a directing group. The new iron-catalyzed method does not require a directing group, and instead places tritium at whatever positions in the molecules are the least crowded.

“Radiolabeled compounds help medicinal chemists get a better picture of what actually happens to the drug by showing how the drug is metabolized and cleared,” said David Hesk, a collaborator at Merck and co-author on the work. By rapidly assessing the compounds’ metabolism early on, scientists can shorten the time it takes to develop and bring a drug to market. “Having another labeling reaction is very powerful because it gives radiochemists another tool in the toolbox,” he said.

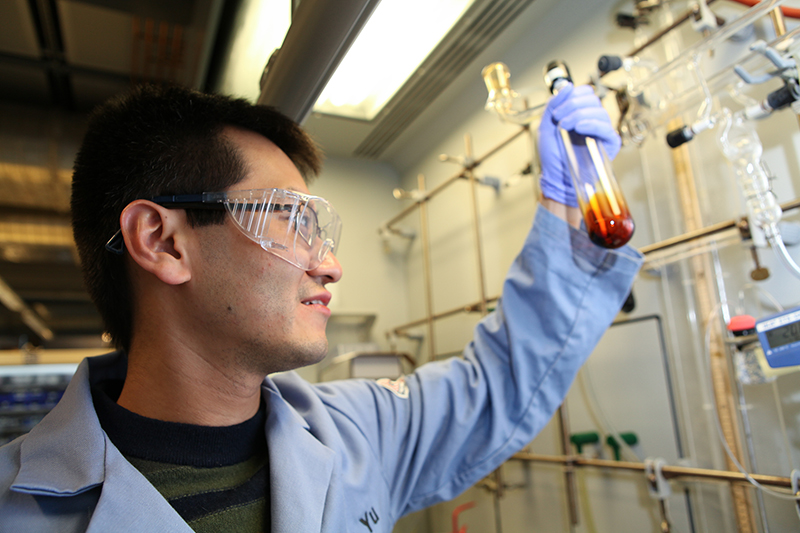

This unique reactivity was actually discovered unexpectedly. Renyuan Pony Yu, a graduate student in the Chirik lab, had originally set out to use their iron catalyst for a different reaction that they were collaborating on with Merck. To study the iron catalyst’s capabilities, Yu subjected it to a technique called proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), which allows chemists to deduce the positions of hydrogen atoms in molecules.

“We started seeing this beautiful, very systematic pattern of signals in the NMR, but we didn’t really know what they were,” said Yu, who is first author on the new study. Particularly puzzling was the fact that the pattern of signals would disappear over time.

The researchers turned to Istvan Pelczer, Director of the NMR Facility at Princeton chemistry and co-author on the work, who developed a special technique that helped them analyze the signals with much greater confidence. Using this method, they realized that the iron catalyst was reacting with the liquid solvent used to dissolve the NMR sample. The solvent’s deuterium atoms, another form of hydrogen that has one extra neutron and is not radioactive, were replacing the hydrogen atoms.

It wasn’t until Yu presented his findings to Matt Tudge, the Princeton authors’ collaborator at Merck, that the catalyst’s potential to introduce tritium atoms into radiolabeled molecules was recognized. “This is a classic example where you really need both partners,” Chirik said. “We were the catalyst experts, but they were the applications experts.”

Though tritium-labeled compounds are used mostly in metabolism studies, they can also be helpful at the very outset of a drug-discovery project to identify a biological target that the potential drugs can be tested against. The biological target could be an enzyme or protein associated with a certain disease. For example, statins are a well-known class of cholesterol-lowering drugs that target a specific enzyme in the body called HMG-CoA reductase.

To explore the scope of the reaction, Yu first optimized the reaction to incorporate deuterium atoms, which is commonly accepted as a model system for tritium. He found that the iron catalyst was surprisingly robust and successfully labeled many different types of compounds, including some from Merck’s library of past drug candidates.

“It was a very exciting project for me because I got to work with real drugs that are fully functionalized and useful,” Yu said. One of their test substrates was Claritin, which Yu bought from a local store; he extracted its active ingredient back in the lab.

Finally, Yu traveled to Merck’s campus in Rahway, where he received radioactivity training — Chirik’s laboratory isn’t equipped to handle radioactivity — and performed the reactions using tritium gas. The reactions were run in a special apparatus that looks like a steel-lined box and releases radioactive tritium gas. The apparatus can capture any unspent gas to limit the amount of radioactive waste produced.

Chemists take care to handle radioactive compounds and waste very carefully, but tritium’s radioactivity is so weak that the particles it emits cannot penetrate simple glassware. For this reason, tritium-labeled compounds can’t be used in any human imaging studies such as PET scans, which require radiolabeled compounds that emit high-energy particles.

This past summer, Yu presented the preliminary results of the iron-catalyzed reaction at the 2015 International Isotope Society Symposia to researchers in the radiolabeling and pharmaceutical community. They were very excited about the research and eager to use the catalyst in their own studies, Yu said.

But the major challenge for the researchers is that the iron catalyst is extremely air and moisture sensitive, and it can only be handled inside a glovebox, a special chamber in which oxygen and water vapor have been excluded. The Chirik group is working to develop a more stable catalyst that can be made commercially available, and have recently entered into a partnership with Green Center Canada, a company that helps bring academic research to market.

In the meantime, the Chirik group has found that the iron catalyst can replace hydrogen atoms with other groups besides deuterium and tritium atoms and is extending this chemistry into many other projects in the lab.

“This project is always going to be a special one for me because it’s kind of a pivot point for the type of chemistry that our group can do,” Chirik said, “and there’s this really cool application.”

Yu, R. P.; Hesk, D.; Rivera, N.; Pelczer, I.; Chirik, P. J. “Iron-Catalyzed Tritiation of Pharmaceuticals.” Nature, 2016, DOI: 10.1038/nature16464.

This work was supported by Merck & Co. and Princeton University’s Intellectual Property Accelerator Fund.

You must be logged in to post a comment.