Political Attitudes

The Dayton Agreement established a system in which ethnic interests were formalized into the political system. The Serbs interests came from the subnational Republika Srpska, while Croat and Bosniak interests would transmit through the analogous Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This regimented, “top-down” approach to ethnicity has transformed Bosnia’s three constituent groups from expressions of identification to pseudo-racial deterministic designations (Farrand, 3).

Attitudes about race and ethnicity in Bosnia have likewise solidified along political lines. Each constituent group has an institutional vehicle to advance its own self-interests. Any push for political change outside of the racial framework puts the advocating constituent group at risk of losing ground. This environment has led political parties to form and persist along racial boundaries (Bose, 119). Furthermore, the necessity of relying on race-based parties has polarized the countries more diverse regions. Mostar, the historic capital of Herzegovina, is the site of a particularly vehement Bosniak-Croat rivalry (Bose, 145).

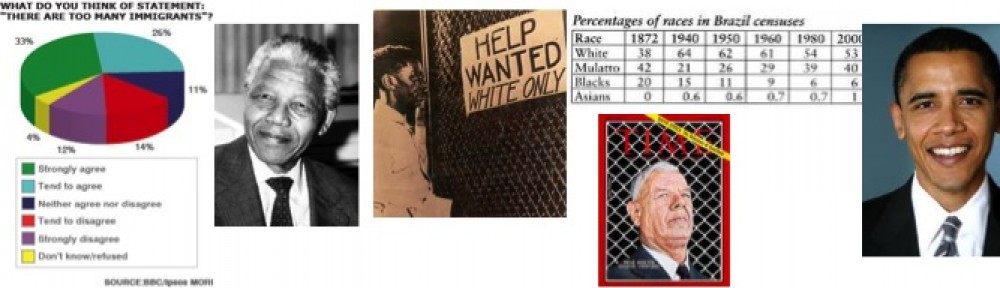

Group size and geography has affected each constituent group’s attitude towards Bosnia.The Bosniaks push for new style of government that would carry give the central government more power than it has in the Dayton system. Bosnia’s demographics justify this strategy. Although no one group holds a majority in Bosnia, the Bosniaks are close, at 48% of the population (CIA World Factbook). If Bosnia were to have a strong centralized government, then Bosniaks would hold the most cards. Croats, being the smallest group at 14%, are against increased centralization, and even want further autonomy from the other constituent groups. A 2011 survey of Mostar and Novi Travnik (a city with a split Bosniak-Croat population) showed that the political aims of Bosniaks and Croats were wildly different when concerning political integration.

The mechanisms of the Dayton system have prevented the Bosniaks’ initiatives from finding success (See Institutions and Preference Policies for an overview of the Dayton system). The Serbs hold a strong majority in the Republika Srpska, and without the approval of the RS no central government reform can pass. Because the Dayton Agreement magnified the Serbs’ voice through the RS, it is in the group’s best interest to keep the status quo or secede entirely (Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, 9).

The status quo, it appears, is not enough for the Republika Srpska. By thwarting any attempts at centralization, the RS has bought time to autonomize its own subnational agencies. Although the consolidation of Federation and RS militaries struck a blow to this scheme, the policies of the Republika have, in general, made Bosnia’s subnational entities more independent of each other, not less. Strategic alliances with Croat parties have assisted in keeping centralization reform at bay, and adoption of pro-EU measures has left the aggressive Serb entity in good standing with pro-reform observers (Centre for Eastern Studies 12(109), 3).

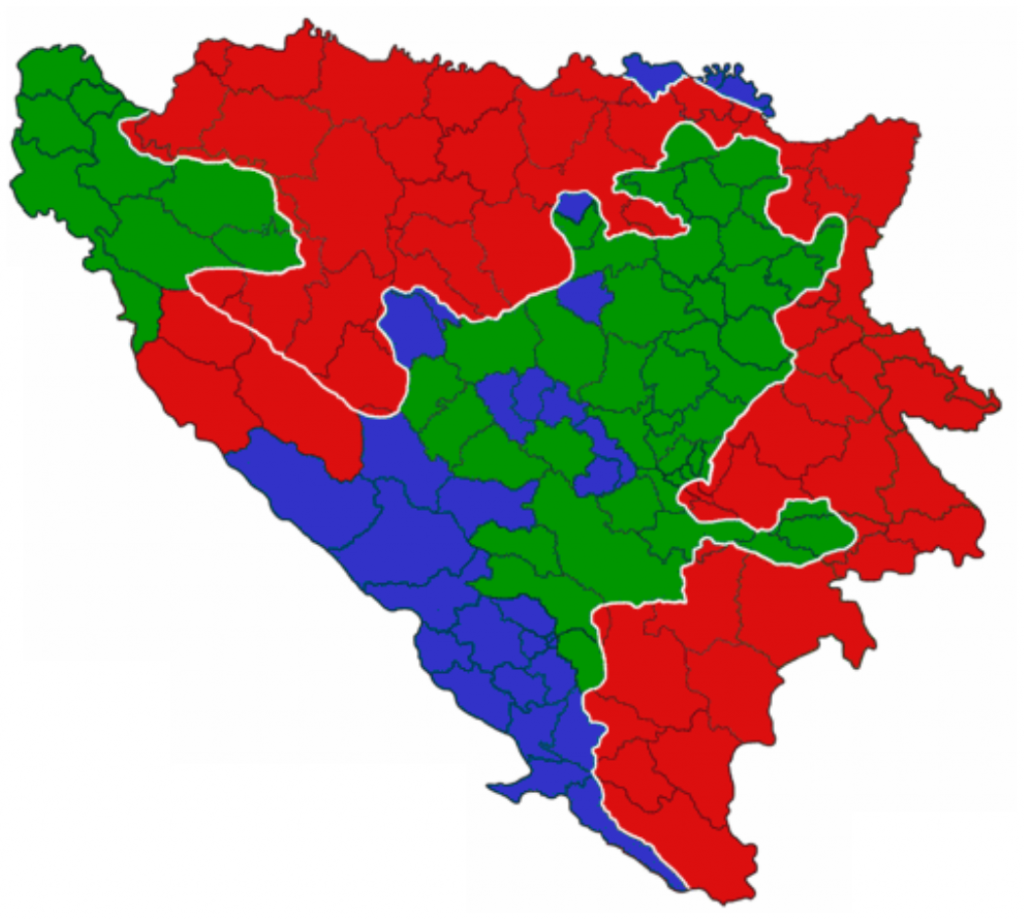

The Serbs have been able to co-opt Croat political capital because the stipulations of the Dayton Agreement left the latter – always the smallest Bosnian group – subservient to the Federation’s Bosniak majority. Croats understandably feel that, by being a minority in “their” subnational entity, they have been paralyzed from enacting political change. Many Croats long for their own autonomous entity (Bose, 128) and Bosnian Serbs, eager to whittle away Bosniak influence, have embraced this proposa with open arms (Centre for Eastern Studies 12(109), 3). However, an examination of Bosnia’s current ethnic map exhibits why a “Croat Republic” would be difficult to parse out.

Estimated ethnic map of Bosnia, circa 2005. Notice not only the discontinuity of Croat territory, but also the sizable enclave of Bosniaks in the country's west.

The result is a political situation where the plurality of pro-unity Bosniaks is vetoed by Serbs fearing Bosniak dominance and Croats longing for enhanced political interests. Nearly 20 years after the Dayton Agreement first attempted to quell ethnic tensions, Bosniak, Croat, and Serb political interests have only become more entrenched. Nobody can say whether the outcome will be a preserved status quo, tri-state agreement, or even a politically independent Republika Srpska, but most parties can agree that centralization is not along the path of least resistance.

Social Attitudes

The most befuddling part of racial attitude is Bosnia is the disconnect between political and social views. A 2005 study by Kristin Bakke of Leiden University concluded that these was no significant social distance between Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs in Bosnia. At least in the social sphere, the constituent groups trusted eachother and did not promote segregation in their every day life (Bakke, 237).

So why the disconnect? It is my suspicion that the Dayton system has allowed political separation to exist because racial parties are the only way a Bosnian can hope to have his or her voice heard. The separation of political office by race forces Bosnians to think in racial terms when entering the voting booth. They may be well-integrated in their social lives, but when it comes to political matters victories are won and lost for “Bosniaks” or “Croats,” not the left or right wing. In other words, hostile political attitudes exist because the Dayton system pits groups against each other for power.

Attitudes in Bosnia and Herzegovina – A Comparative Perspective

Socially, inter-group trust in Bosnia is surprisingly high for a country with its past. Although its hard to make pairwise comparisons, it appears that Bosnia’s groups trust each other more than those in Canada (Chen, Attitudes). Bosnia fairs far better than Turkey, which exhibits a high level of suspicion between groups (Baptiste, Attitudes). It is difficult to make a fair comparison with the Dominican Republic’s pigmentocracy because Bosnia’s modern pseudo-racial groups were established by religious as opposed to phenotypical differences. France also presents a difficult comparison, as prejudice in France is largely directed towards immigrants (Renfro, Attitudes). Bosnia, on the other hand, has only experiences a small amount of immigration in recent years, mostly from returning refugees (International Organization for Migration, 13).

Bosnia sets itself apart from the other countries in this study because racial attitudes have a political dimension in addition to a social one. This reality forces Bosnians to play a political game in which political polarization translates to racial polarization in government. This system does not exist in the other countries, so it is difficult to make an accurate comparison.

Unfortunately, comparison of up-to-date World Value Survey information is unavailable because Bosnia has declined to participate since the 2001 cycle.