By Staff

An international team of researchers has predicted the existence of a new type of particle called the type-II Weyl fermion in metallic materials. When subjected to a magnetic field, the materials containing the particle act as insulators for current applied in some directions and as conductors for current applied in other directions. This behavior suggests a range of potential applications, from low-energy devices to efficient transistors.

The researchers theorize that the particle exists in a material known as tungsten ditelluride (WTe2), which the researchers liken to a “material universe” because it contains several particles, some of which exist under normal conditions in our universe and others that may exist only in these specialized types of crystals. The research appeared in the journal Nature this week.

The new particle is a cousin of the Weyl fermion, one of the particles in standard quantum field theory. However, the type-II particle exhibits very different responses to electromagnetic fields, being a near perfect conductor in some directions of the field and an insulator in others.

The research was led by Princeton University Associate Professor of Physics B. Andrei Bernevig, as well as Matthias Troyer and Alexey Soluyanov of ETH Zurich, and Xi Dai of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Physics. The team included Postdoctoral Research Associates Zhijun Wang at Princeton and QuanSheng Wu at ETH Zurich, and graduate student Dominik Gresch at ETH Zurich.

The particle’s existence was missed by physicist Hermann Weyl during the initial development of quantum theory 85 years ago, say the researchers, because it violated a fundamental rule, called Lorentz symmetry, that does not apply in the materials where the new type of fermion arises.

Particles in our universe are described by relativistic quantum field theory, which combines quantum mechanics with Einstein’s theory of relativity. Under this theory, solids are formed of atoms that consist of a nuclei surrounded by electrons. Because of the sheer number of electrons interacting with each other, it is not possible to solve exactly the problem of many-electron motion in solids using quantum mechanical theory.

Instead, our current knowledge of materials is derived from a simplified perspective where electrons in solids are described in terms of special non-interacting particles, called quasiparticles, that move in the effective field created by charged entities called ions and electrons. These quasiparticles, dubbed Bloch electrons, are also fermions.

Just as electrons are elementary particles in our universe, Bloch electrons can be considered the elementary particles of a solid. In other words, the crystal itself becomes a “universe,” with its own elementary particles.

In recent years, researchers have discovered that such a “material universe” can host all other particles of relativistic quantum field theory. Three of these quasiparticles, the Dirac, Majorana, and Weyl fermions, were discovered in such materials, despite the fact that the latter two had long been elusive in experiments, opening the path to simulate certain predictions of quantum field theory in relatively inexpensive and small-scale experiments carried out in these “condensed matter” crystals.

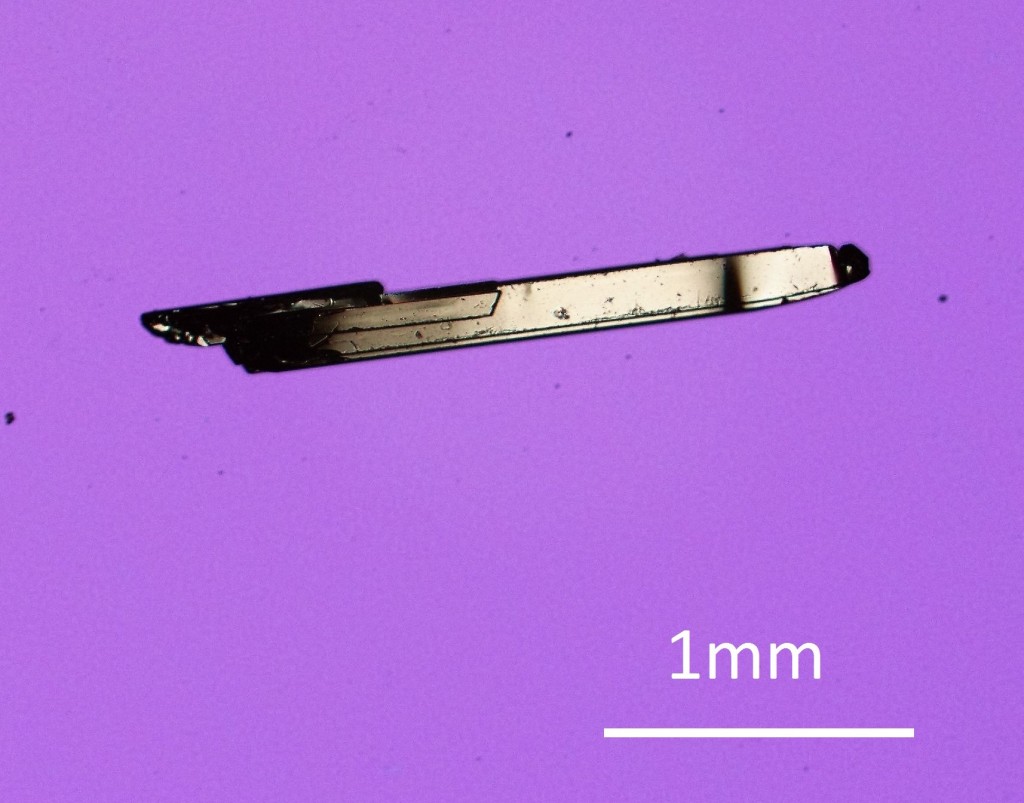

These crystals can be grown in the laboratory, so experiments can be done to look for the newly predicted fermion in WTe2 and another candidate material, molybdenum ditelluride (MoTe2).

“One’s imagination can go further and wonder whether particles that are unknown to relativistic quantum field theory can arise in condensed matter,” said Bernevig. There is reason to believe they can, according to the researchers.

The universe described by quantum field theory is subject to the stringent constraint of a certain rule-set, or symmetry, known as Lorentz symmetry, which is characteristic of high-energy particles. However, Lorentz symmetry does not apply in condensed matter because typical electron velocities in solids are very small compared to the speed of light, making condensed matter physics an inherently low-energy theory.

“One may wonder,” Soluyanov said, “if it is possible that some material universes host non-relativistic ‘elementary’ particles that are not Lorentz-symmetric?”

This question was answered positively by the work of the international collaboration. The work started when Soluyanov and Dai were visiting Bernevig in Princeton in November 2014 and the discussion turned to strange unexpected behavior of certain metals in magnetic fields (Nature 514, 205-208, 2014, doi:10.1038/nature13763). This behavior had already been observed by experimentalists in some materials, but more work is needed to confirm it is linked to the new particle.

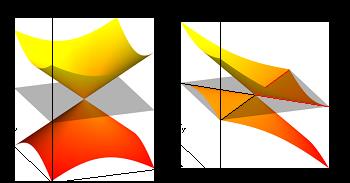

The researchers found that while relativistic theory only allows a single species of Weyl fermions to exist, in condensed matter solids two physically distinct Weyl fermions are possible. The standard type-I Weyl fermion has only two possible states in which it can reside at zero energy, similar to the states of an electron which can be either spin-up or spin-down. As such, the density of states at zero energy is zero, and the fermion is immune to many interesting thermodynamic effects. This Weyl fermion exists in relativistic field theory, and is the only one allowed if Lorentz invariance is preserved.

The newly predicted type-2 Weyl fermion has a thermodynamic number of states in which it can reside at zero energy – it has what is called a Fermi surface. Its Fermi surface is exotic, in that it appears along with touching points between electron and hole pockets. This endows the new fermion with a scale, a finite density of states, which breaks Lorentz symmetry.

Right: The newly discovered type-II Weyl fermion. At zero energy, a large number of allowed states are still available. This allows for the presence of superconductivity, magnetism, and pair-density wave phenomena.

Credit

B. Andrei Bernevig et al.

The discovery opens many new directions. Most normal metals exhibit an increase in resistivity when subject to magnetic fields, a known effect used in many current technologies. The recent prediction and experimental realization of standard type-I Weyl fermions in semimetals by two groups in Princeton and one group in IOP Beijing showed that the resistivity can actually decrease if the electric field is applied in the same direction as the magnetic field, an effect called negative longitudinal magnetoresistance. The new work shows that materials hosting a type-II Weyl fermion have mixed behavior: While for some directions of magnetic fields the resistivity increases just like in normal metals, for other directions of the fields, the resistivity can decrease like in the Weyl semimetals, offering possible technological applications.

“Even more intriguing is the perspective of finding more ‘elementary’ particles in other condensed matter systems,” the researchers say. “What kind of other particles can be hidden in the infinite variety of material universes? The large variety of emergent fermions in these materials has only begun to be unraveled.”

Researchers at Princeton University were supported by the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Office of Naval Research, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the W.M. Keck Foundation. Researchers at ETH Zurich were supported by Microsoft Research, the Swiss National Science Foundation and the European Research Council. Xi Dai was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the 973 program of China and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The article, “Type II Weyl Semimetals,” by Alexey A. Soluyanov, Dominik Gresch, Zhijun Wang, QuanSheng Wu, Matthias Troyer, Xi Dai, and B. Andrei Bernevig was published in the journal Nature on November 26, 2015.

You must be logged in to post a comment.