By Catherine Zandonella, Office of the Dean for Research

Researchers at Princeton University have observed a bizarre behavior in a strange new crystal that could hold the key for future electronic technologies. Unlike most materials in which electrons travel on the surface, in these new materials the electrons sink into the depths of the crystal through special conductive channels.

“It is like these electrons go down a rabbit hole and show up on the opposite surface,” said Ali Yazdani, the Class of 1909 Professor of Physics. “You don’t find anything else like this in other materials.”

The research was published in the journal Science.

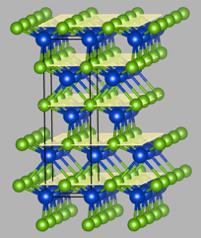

Yazdani and his colleagues discovered the odd behavior while studying electrons in a crystal made of layers of tantalum and arsenic. The material, called a Weyl semi-metal, behaves both like a metal, which conducts electrons, and an insulator, which blocks them. A better understanding of these and other “topological” materials someday could lead to new, faster electronic devices.

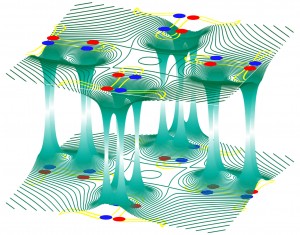

The team’s experimental results suggest that the surface electrons plunge into the crystal only when traveling at a certain speed and direction of travel called the Weyl momentum, said Yazdani. “It is as if you have an electron on one surface, and it is cruising along, and when it hits some special value of momentum, it sinks into the crystal and appears on the opposite surface,” he said.

These special values of momentum, also called Weyl points, can be thought of as portals where the electrons can depart from the surface and be conducted to the opposing surface. The theory predicts that the points come in pairs, so that a departing electron will make the return trip through the partner point.

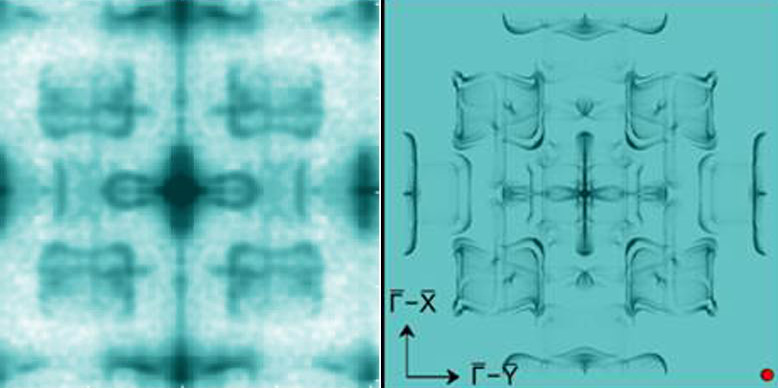

The team decided to explore the behavior of these electrons following research, published in Science last year by another Princeton team and separately by two independent groups, revealing that electrons in Weyl semi-metals are quite unusual. For example, their experiments implied that while most surface electrons create a wave pattern that resembles the spreading rings that ripple out when a stone is thrown into a pond, the surface electrons in the new materials should make only a half circle, earning them the name “Fermi arcs.”

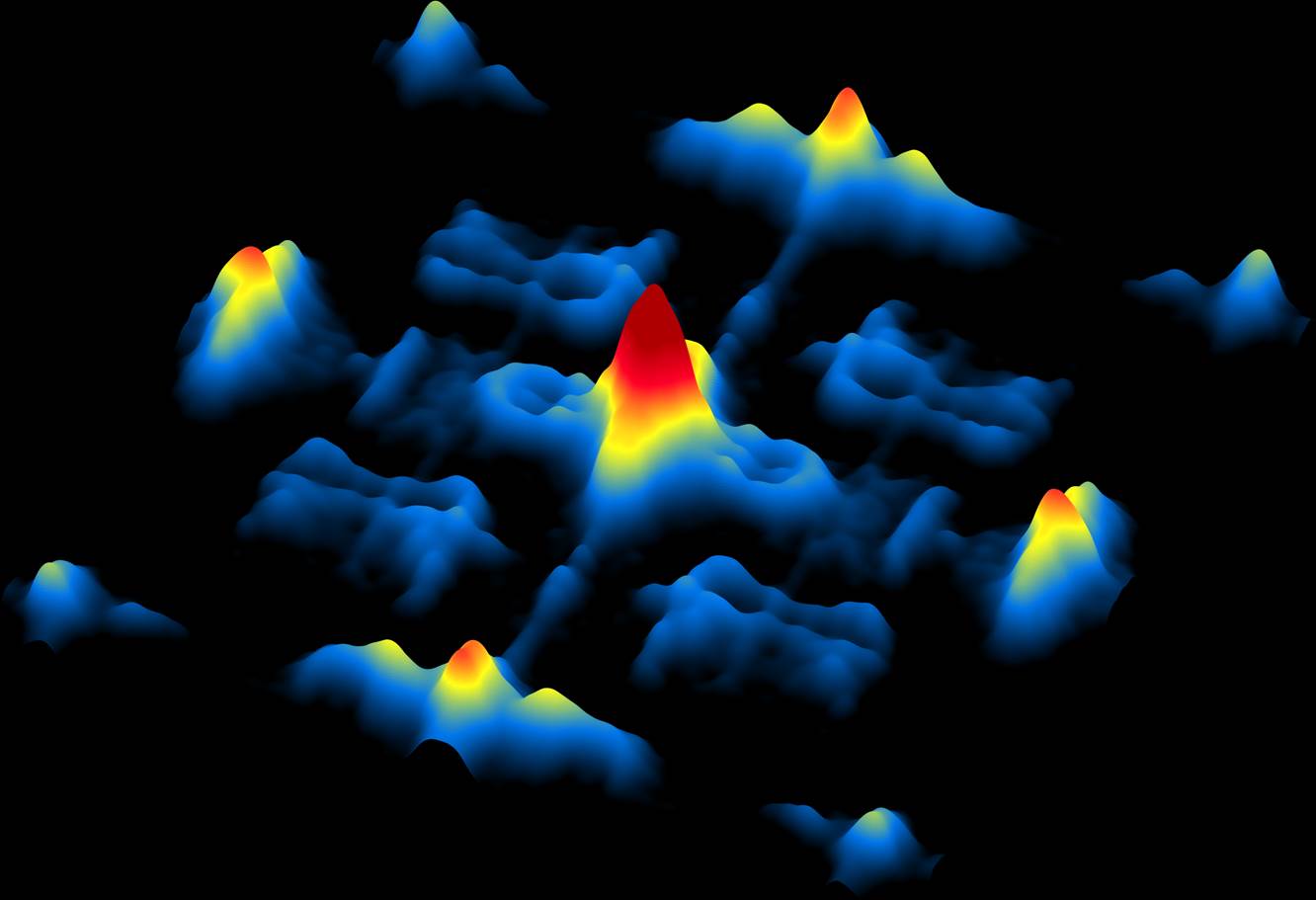

To get a more direct look at the patterns of electron flow in Weyl semi-metals, postdoctoral researcher Hiroyuki Inoue and graduate student András Gyenis in Yazdani’s lab, with help from graduate student Seong Woo Oh, used a highly sensitive instrument called a scanning tunneling microscope, one of the few tools that can observe electron waves on a crystal surface.

They obtained the tantalum arsenide crystals from graduate student Shan Jiang and assistant professor Ni Ni at the University of California-Los Angeles.

The results were puzzling. “Some of the interference patterns that we expected to see were missing,” Yazdani said.

To help explain the phenomenon, Yazdani consulted B. Andrei Bernevig, associate professor of physics at Princeton, who has expertise in the theory of topological materials and whose group was involved in the first predictions of Weyl semi-metals in a 2015 paper published in Physical Review X.

Bernevig, with help from postdoctoral researchers Jian Li and Zhijun Wang, realized that the observed pattern made sense if the electrons in these unusual materials were sinking into the bulk of the crystal. “Nobody had predicted that there would be signals of this type of transport from a scanning tunneling microscope, so it came as a bit of a surprise,” said Bernevig.

The next step, said Bernevig, is to look for the behavior in other crystals.

The research at Princeton was supported by the Army Research Office Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative program (W911NF-12-1-0461), the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation as part of EPiQS initiative (GBMF4530), the National Science Foundation Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers programs through the Princeton Center for Complex Materials (DMR-1420541, NSF-DMR-1104612, NSF CAREER DMR-0952428), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the W. M. Keck Foundation. This project was also made possible through use of the facilities at Princeton Nanoscale Microscopy Laboratory (ARO-W911NF-1-0262, ONR-N00014-14-1-0330, ONR-N00014-13-10661), the U.S. Department of Energy Basic Energy Sciences (DOE-BES) Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the U.S. Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command Meso program (N6601-11-1-4110, LPS and ARO-W911NF-1-0606), and the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Transformative Technology Fund at Princeton. Work at University of California–Los Angeles was supported by the DOE-BES (DE-SC0011978).

The article, “Quasiparticle interference of the Fermi arcs and surface-bulk connectivity of a Weyl semimetal,” by Hiroyuki Inoue, András Gyenis, Zhijun Wang, Jian Li, Seong Woo Oh, Shan Jiang, Ni Ni, B. Andrei Bernevig,and Ali Yazdani, was published in the March 11, 2016 issue of the journal Science.

Further reading:

M. Weng, C. Fang, Z. Fang, B. A. Bernevig, X. Dai, Phys. Rev. X 5, 011029 (2015)

Q. Lv et al., Phys. Rev. X 5, 1–8 (2015)

X. Yang et al., Nat. Phys. 11, 728–732 (2015)

Y. Xu et al., Science 349, 613–617 (2015)

You must be logged in to post a comment.