SECTION 3: IMPACT OF SURREALIST EXHIBITIONS OF MUSEUMS TODAY

The influence of the Surrealists in the art movements that came after them is widely recognized, but controversy exists concerning the nature of their legacy. In particular, while elements of the aesthetic innovations that Surrealists introduced to the gallery space are recognizable, the lasting impact of the political aspects of their work is more of an open questions. In many cases, it seems like the aesthetics of the Surrealists has been appropriated and recuperated by the institutions of the art world without the political implications that were critical to the work of the initial Surrealists. We looked at two exhibitions that we have personal experience with as test cases.

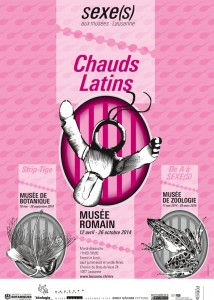

One example of a museum that has incorporated the surrealist aesthetic without necessarily bringing in the political dimension might be the Musee Romain Lausanne-Vidy in Lausanne, Switzerland. This museum transforms its space in order to put on temporary exhibitions.

In their most recent exhibition, entitled “Chauds Latin,” they converted the exhibition space into a womb. The space was set up as a pair of ovarian tubes, and lined with pink, spongy insulation material. The visitor could visit various displays, which were embedded in intimate nooks cut into the walls. To look at the material, the visitor had to push past gauzy curtains to sit in a little alcove, also covered in plush. There were often sonic components to the exhibition as well as visual ones, and adult users were given a phallus-shaped key, which they could insert into vArious locks in order to access more risque material–the exhibition focused on the sexual mores of Ancient Rome, after all.

In their most recent exhibition, entitled “Chauds Latin,” they converted the exhibition space into a womb. The space was set up as a pair of ovarian tubes, and lined with pink, spongy insulation material. The visitor could visit various displays, which were embedded in intimate nooks cut into the walls. To look at the material, the visitor had to push past gauzy curtains to sit in a little alcove, also covered in plush. There were often sonic components to the exhibition as well as visual ones, and adult users were given a phallus-shaped key, which they could insert into vArious locks in order to access more risque material–the exhibition focused on the sexual mores of Ancient Rome, after all.

Other exhibitions have been similarly immersive and interactive, incorporating all the sensory dimensions of the space into the exhibition, and encouraging visitors to touch and play. In “Mystere,” a 2012 exhibition, the entire exhibition space was remodeled to imitate the inside of a house–with a living room, kitchen, bedroom and bathroom. In each room, visitors were encouraged to interact with the space just as they might with a normal home– to open up books, turn on the tap or the television, flush the toilet, open the bathroom cabinet. Inside the cabinet, however, were various remedies from Roman times and today that were linked to superstition. Similarly, the program on the television traced various instances of superstition in popular media back to equivalent Roman superstition. In the kitchen, the superstitions addressed revolved around food.

In this way, the exhibition attempted to deliver messages about the link between superstitions and our daily practice of life, and to create a link between the past and the present.

Other exhibitions–a Minotaur maze, with epic challenges to be surmounted, or a board game exhibition, in which the visitor had to solve each room in order to move to the next–were similarly immersive and interactive.

This immersion and interactivity, however, was mostly harnessed to teach ideas about Ancient Rome, or to give the viewer pleasure and enjoyment. It is possible to read these exhibitions as statements about the role of the museum, but they do not make the viewer uncomfortable, or disturb them.

Yet some museums are creating exhibitions that are more potentially political. The Palais de Tokyo, a Parisian contemporary art center, offers immersive experiences in its seasonal exhibitions. Most recently, NOUVELLES VAGUES and INSIDE took over the entire 22 000 square meters of the exhibition space prompting audience participation in multimedia activities. Henrique Oliverira’s Baitogogo (Palais de Tokyo, Henrique Oliveira, Baitogogo), is an installation piece that uproots the boundaries between nature and infrastructure. The Portuguese artists’ invasive piece destroys the center’s internal architecture; he organically weaves wooden branches into the plaster columns, allowing nature to serve as structural foundation. Oliverira explores the connections between art and science, sculpting a landscape of natural outgrowths akin to tumors. Numen/For Use’s Tape installation creates a three-dimensional web of scotch tape, which can be explored by the Palais visitors. The art group designs a crawl space for the visitors, establishing a new “inside” for the Palais. Vision is blurred both on the inside and the outside of the web; the opaque layers of tape foster a mysterious understanding of environment whose dimensions cannot be seen, but can be touched. “The bravest have the possibility of penetrating into this protective matrix and the journey through it constitutes the first stage in the exploration of an inner space that is physical as much as it is mental” (Palais de Tokyo, “NUMEN/FOR USE”): this binary mission is not dissimilar to that of the Surrealists’ who sought to provide exhibition spaces that challenged the visitor’s sensory landscape, testing the limits of human perception and experience. The Palais de Tokyo and its exhibits are strongly influenced by the Surrealist movement, playing with the subversion of the everyday exhibition space to create a more dynamic and interactive environment for the audience.

Yet some museums are creating exhibitions that are more potentially political. The Palais de Tokyo, a Parisian contemporary art center, offers immersive experiences in its seasonal exhibitions. Most recently, NOUVELLES VAGUES and INSIDE took over the entire 22 000 square meters of the exhibition space prompting audience participation in multimedia activities. Henrique Oliverira’s Baitogogo (Palais de Tokyo, Henrique Oliveira, Baitogogo), is an installation piece that uproots the boundaries between nature and infrastructure. The Portuguese artists’ invasive piece destroys the center’s internal architecture; he organically weaves wooden branches into the plaster columns, allowing nature to serve as structural foundation. Oliverira explores the connections between art and science, sculpting a landscape of natural outgrowths akin to tumors. Numen/For Use’s Tape installation creates a three-dimensional web of scotch tape, which can be explored by the Palais visitors. The art group designs a crawl space for the visitors, establishing a new “inside” for the Palais. Vision is blurred both on the inside and the outside of the web; the opaque layers of tape foster a mysterious understanding of environment whose dimensions cannot be seen, but can be touched. “The bravest have the possibility of penetrating into this protective matrix and the journey through it constitutes the first stage in the exploration of an inner space that is physical as much as it is mental” (Palais de Tokyo, “NUMEN/FOR USE”): this binary mission is not dissimilar to that of the Surrealists’ who sought to provide exhibition spaces that challenged the visitor’s sensory landscape, testing the limits of human perception and experience. The Palais de Tokyo and its exhibits are strongly influenced by the Surrealist movement, playing with the subversion of the everyday exhibition space to create a more dynamic and interactive environment for the audience.

This exhibition does appear to challenge museum norms and to push boundaries, and as such might be read as at least partially political.