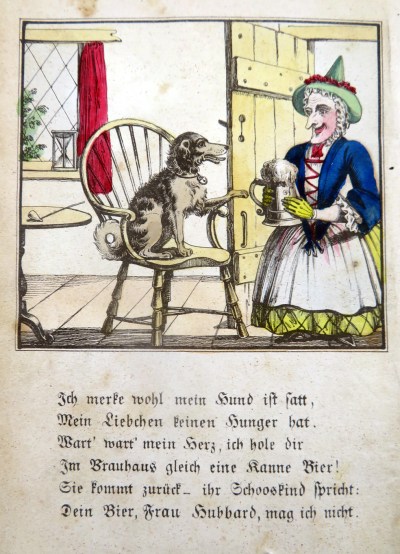

The third plate illustrating one of the less familiar rhymes in Songs for the Nursery. London: Printed for Tabart and Co., [1808]. (Cotsen 130)

Who was responsible for it? A comment in Charles Lamb’s letter to Dorothy Wordsworth of June 2 1804 offers evidence that Songs was compiled by Eliza Fenwick, a aspiring novelist in the 1790s, who was struggling to support her family in the 1880s by writing children’s books and taking on literary piece work. Fenwick’s biographer Lissa Paul believes that she solicited examples from her literary friends and Dorothy Wordsworth obliged by sending “Arthur O’Brower” and some other “scraps.” It’s also very likely that the work’s subtitle “Collected from the Works of the most Renowned Poets” was a tongue-in-cheek elevation of the old nurses who sang them, a joke that the editors of the Songs’ predecessors Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song-book (1744) and Mother Goose’s Melodies (1772) had indulged in.

Bewick’s cut for “Bah, bah, black sheep.” Mother Goose’s Melody. London: Printed for T. Carnan, [1784]. (Cotsen 62899)

The illustrator of Songs was not identified on the title page, as was usually the case during this period. Marjorie Moon, the collector/bibliographer of Tabart’s children’s books, did not venture a guess as to the creator of the excellent designs. It turns out to have been a well-known, versatile, well-connected artist, William Marshall Craig (d.1827). The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that Craig was considered one of the most distinguished designers of woodblocks from 1800 until his death. “Charming but not individual” was the verdict of Houfe’s Dictionary of 19th Century Illustrators of Craig as an illustrator.” No other reference sources mention that Craig produced children’s book illustrations, perhaps because it seemed an unlikely way for the drawing master for Princess Charlotte, daughter of the Prince of Wales, miniature painter to the Duke and Duchess of York, and painter in watercolors to Queen Charlotte to supplement his income.

Detail from the engraved frontispiece of The Juvenile Preceptor. Ludlow: George Nicholson, 1800. (Cotsen 5110)

Nevertheless, that is exactly what Craig did for a time. Some of his work 1800-1806 features a highly recognizable type of child. This detail from Craig’s frontispiece design (signed in the lower left) from The Juvenile Preceptor (Ludlow: George Nicholson, 1800) has the earliest example I have found. The boy in the fashionable skeleton suit reading to his mother is sturdy and chubby lad with a round face and a cap of wavy hair.

This drawing book by Craig, which I had the pleasure of seeing in the fabulous collection of Rosie and David Temperley is filled with pictures of boys who bear a family resemblance to the one in The Juvenile Preceptor. .

From Craig’s Complete Instructor in Drawing Figures. Collection of Rosie and David Temperley, Edinburgh.

We know that Tabart employed Craig because Marjorie Moon discovered advertisements for Tabart’s six-penny series, “Tales for the Nursery,” that credited the artist with the designs for the illustrations. Some of the plates in the early editions as well as the ones recycled in Tabart’s Collection of Popular Stories for the Nursery, were signed with Craig’s name as the “inventor.” In the detail of the frontispiece for the Dick Whittington to the right, the hero holding the stripy tomcat may be wearing a cloak and tights instead of a skeleton suit, but he has the tell-tale bowl hair cut.

Some years ago Mr. Cotsen acquired an original pen and ink drawing for the plate of “Little Boy Blue” in Songs. The dealer attributed by the dealer to William Marshall Craig, I was never sure if it were wishful thinking because there wasn’t a citation to a reference book or scholarly monograph on Craig. After lining up all these other little boys in other works whose attributions to Craig are secure, there can’t be much doubt that he did Songs for the Nursery as well. The plate for Little Jack Horner follows, for those who aren’t entirely convinced. .

.  On the strength of this evidence, I feel pretty confident that a handful of other Tabart classics also were illustrated by Craig: Fenwick’s Life of Carlo (1804); Mince Pies for Christmas (1805); The Book of Games (1805), and M. Pelham’s Jingles; or Original Rhymes for Children (1806), which is pictured below. In a review of The Book of Games, Mrs. Trimmer, herself the daughter of an engraver, noted that while the quality of the engraving was not always good, it did not obscure the excellence of the designs.

On the strength of this evidence, I feel pretty confident that a handful of other Tabart classics also were illustrated by Craig: Fenwick’s Life of Carlo (1804); Mince Pies for Christmas (1805); The Book of Games (1805), and M. Pelham’s Jingles; or Original Rhymes for Children (1806), which is pictured below. In a review of The Book of Games, Mrs. Trimmer, herself the daughter of an engraver, noted that while the quality of the engraving was not always good, it did not obscure the excellence of the designs.  Last but not least, an extra dollop of frosting on the cake. While working on this post, I discovered that my colleague Julie Mellby, the curator of Graphic Arts, has a second drawing from Songs pasted into an album of Marshall Craig drawings she described in a 2010 post. It’s the fifth illustration she reproduced and it is for “Cushy cow bonny.” Could one or two more of the drawings for Songs be among the unidentfied Craig drawings in the Victoria & Albert archive?

Last but not least, an extra dollop of frosting on the cake. While working on this post, I discovered that my colleague Julie Mellby, the curator of Graphic Arts, has a second drawing from Songs pasted into an album of Marshall Craig drawings she described in a 2010 post. It’s the fifth illustration she reproduced and it is for “Cushy cow bonny.” Could one or two more of the drawings for Songs be among the unidentfied Craig drawings in the Victoria & Albert archive?