Group Number: 18

Names:

Mario Alvarez ’14, Valya Barboy ’15, Bonnie Eisenman ’14, Erica Portnoy ’15.

Problem and Solution Overview:

Organizing books, finding them, and remembering where specific books are can be difficult. It becomes exceedingly difficult as the number of books grows, and as people begin using books both for work and pleasure. Moreover, people who have multiple locations that contain books (multiple rooms, home and office, etc.) have trouble remembering which books are where, and continually end up needing a book that is inaccessible. Our solution is a bookshelf that has an RFID scanner on it. Each book on the shelf has an RFID tag placed on it. The shelf knows which books it contains, and can inform the user that a book is on it when a user queries a software system. An important aspect of our system is that it doesn’t require the user to make lasting modifications to their books, which was a concern of most of the potential users we interviewed.

Descriptions of Users Observed:

The target user group we ended up interviewing were researchers who own a lot of books. The idea behind this target user group was to have people who use books in multiple ways, and could therefore have more specific organizational needs. Moreover, these users tended to have multiple locations for storing books — at home, in the office, study carrels — and tended to also have borrowed books, which would need to be returned. This makes it more problematic if they lose or misplace books. We ended up interviewing some graduate students, in mathematics and physics, and some professors of comparative literature, English, and computer science. We wanted to see how people in different disciplines use books. For example, we noticed that those in the arts tended to have significantly larger numbers of books (by orders of magnitude), and therefore were forced to already have established organizational systems. Additionally, users in technical fields favored e-books for pleasure reading, but avoided them for research due to impracticality; the users we interviewed in the arts and humanities expressed extreme dislike for e-books. Based on this, we realized that our system would be better for a target audience of people who own no more than a few hundred books.

CI Interview Descriptions:

We observed two mathematics graduate students in their respective offices. They both kept their math books in the office, and their pleasure reading at home. The first student had some problems remembering which of her books were at home and which were in her office. The second graduate student had everything perfectly organized — fiction was organized by what he had or hadn’t read and then by author; mathematics was organized by subject — and knew exactly where everything was. He generally can locate a book without a problem (and demonstrated this by finding any book we asked for), but sometimes forgets he has certain books and buys multiple copies. Both used e-books only when the material was otherwise inaccessible, or when traveling, but preferred to do their reading using physical copies. Both also kept their library books on a separate bookshelf, so as not to misplace them. Finally, both said that an organizational system would be nice to have, especially to remember which books are where, but that they do not want to take the time to scan or otherwise document every book they own.

We also observed a professor of Visual Arts who has thousands of books. He had them organized by topic, language, and time period. He could find any given book within seconds. He also had an expansive library at home, which he used for research and for pleasure. The books he kept in his office were those that could be relevant to the classes he teaches. A problem he acknowledged having was moving books from one location to another (i.e. from his house to his office), but he was very good at remembering where his books were. He also never borrows books, and keeps his library books separate from everything else. Next, we observed an English professor in his home, where he keeps his largest collection of books (he has several personal libraries across his residences and offices). He keeps his books using a loose, informal system of organization, with books roughly organized by topic, and books he is currently using stacked on or near his desk. His book collection is so important to him personally – and he spends so much time with it – that he is more or less able to keep track of where everything is. This is a feat, since he estimates he has a few thousand books in his home alone. This system appeared to work well for him: for instance, after he mentioned Turing in passing, we asked him if he could find a book about Turing for us, and he was immediately able to show us where the book had been, as well as recall that he had moved it to one of his offices some time ago. He feels that strict organizational schemes “demystify” the process of finding books, and that the serendipity of finding a book different from the one he was originally looking for is important to his research.

We also went to the Princeton Public Library and observed people trying to find books on the shelves. They would look up a book on a computer, look along the edges of the bookshelves to find the section, and walk along the aisle until they found the right first number, and then they would look more closely once they were nearby. In order to find the specific book, people looked very closely at the titles and numbers on the shelves. We then observed people shopping at CVS, and noted that they had a very similar tactic: they would look at the aisle sections to determine which aisle to go to, and then look more closely once there. One thing we noticed was that when people look for things they tend to physically run their fingers along the spines, shelves, or objects. If they don’t want to touch the objects, they’ll hover next to them, scanning physically as well as visually.

Answers to Eleven Task Analysis Questions:

1. Who is going to use the system?

Our system could be used by anyone with a personal collection of books. However, we envision it being most useful to people who use physical books for research in technical fields. There is very little chance that people who already have thousands of books will catalog all of them, so they would be less likely to use our system; our system will likely be more amenable to a medium-size collection (up to a few hundred books) than to an extremely large collection anyhow. Though we are designing the system with researchers in mind, it will likely be useful to those outside research fields as well.

2. What tasks do they now perform?

Our target group performs a few key tasks while interacting with their book collections. They search for books that they know are in their collection (though they may not know the books’ exact location). After they are done using a book, they need to be able to return it to their collection. They sometimes need to go through their collection to determine whether they own a particular book. Finally, they need to be able to add new books to their collection. All of these tasks generally operate within the frame of a particular organizational scheme; therefore, implicit in each action is that the user should be able to do it while maintaining the invariants necessary to keep their organizational scheme usable. If they do not do this, the tasks of finding books become difficult.

3. What tasks are desired?

Essentially, the users desire to perform the same set of tasks more efficiently. It can take a long time for a user to determine whether they already own a book, since, without a comprehensive catalog of their collection, they need to examine all their books to determine that they do not have a particular one. Additionally, users need to be able to find books consistently and efficiently; as mentioned above, this is not always the case. Finally, researchers tend to have their book collections spread across multiple locations (for example, their home and their office), so determining which books are in which locations is another important task (this was particularly true of the English professor we interviewed).

4. How are the tasks learned?

Currently users employ some combination of two complementary strategies in order to keep their books organized (i.e., learn and remember where books are). First, they can impose a formal system of organization, grouping books together based on commonalities (as the film professor we interviewed did). In an extreme case, they might use an industrial-strength system such as Dewey Decimal. Second, they can use spatial memory, connecting these groups of books to the parts of the space in which they are stored for more rapid retrieval. Both have drawbacks: maintaining a formal system requires discipline and an investment of time each time a book is stored or retrieved, while using spatial memory effectively requires an intimate familiarity with one’s collection and the space that collection occupies, which can take years to develop.

5. Where are the tasks performed?

Wherever the users keep their book collections – so the home and office, at a minimum; possibly other locations for users whose collections are spread across other locations.

6. What’s the relationship between user & data?

In this case, the data is the set of books the user owns, and where those books are. Users have an expectation of privacy for their book collections, as these can be highly personal in nature. Though sharing the full list of books users own will not be required, users may want to be able to share certain information about their collections with friends (for instance, if their friends want to borrow a book from their collection). Users should be able to access data about their own collections remotely – for example, if a user is at a bookstore, she should be able to look up whether she already owns a copy of a book before buying a new one.

7. What other tools does the user have?

The user currently has standard bookshelves. The user may also have software applications to aid in cataloging, such as BookCrawler, but as the film professor we interviewed mentioned, their utility is questionable because they are not tightly integrated with the physical locations of the books like our system is. Additionally, the user may use a traditional cataloging system (such as Dewey Decimal) in order to precisely specify the correct location for each book; however, this requires knowledge of the system and a large amount of effort to maintain, with the result that few actually use such systems.

8. How do users communicate with each other?

Users may borrow books from each other and lend books to each other. Additionally, they must negotiate with others who share their space to ensure that their system of organization is maintained properly. In the case of the home, this may be with other family members who share shelf space (and who may share the collection, making them users as well). In the case of the office, this may be with co-workers or colleagues (researchers in particular often have shared office space.) Communication tends to be informal, verbal, and in-person.

9. How often are the tasks performed?

This varies greatly from user to user and from collection to collection, depending on the user’s habits and the purpose of the collection (for instance, whether it serves as an archive of old, seldom-used material or an active repository for currently-relevant research). Generally, the tasks of storing and retrieving books already in the collection are performed more frequently (several times a day to a couple of times a week) than adding books or checking whether a book is in the collection (a couple of times a week to a few times a year).

10. What are the time constraints on the tasks?

There are no time constraints per se, but if it takes too long to find a book, the individual may give up (although some, like the English professor we interviewed, value the experience of finding a different book than one originally sought). Doing research efficiently depends on finding research materials quickly, so time is likely most important for professional researchers, who want to free up time to do actual research rather than looking for books.

11. What happens when things go wrong?

If the system is used and then stops working (or stops being used), the user’s book collection may become extremely disorganized. As a result the user may not be able to find her books any longer. This is not a catastrophic result, but may make it difficult for the user to do her job if she is a researcher. The user may also lose books if their organizational system loses track of them. This is a potential problem with our system: since it does not require a particular physical layout of books, if users rely on our system and no longer organize their book collection in conventional ways, their collections will be left in a state of disarray if our system stops working.

Description of Three Tasks:

1. Retrieving a book from the collection

The difficulty of this task currently depends on a number of factors, such as how many different places the user keeps books. None of the users we talked to used a strict organizational scheme, though many had their books roughly sorted based on whether or not they were for research, as well as by topic or by time period. With such a scheme, most users are able to find books with moderate difficulty.

Under our proposed system, the user would be able to simply query our system for the book, which would then indicate its physical location. Our system would therefore make it easy to perform this task.

2. Shelving a new book, or returning a book to the collection

Currently, the difficulty of this task is proportional to both the user’s number of books and the strictness of their organization system. If their system is lax and flexible it might be easy to file a book – but this will make retrieving books difficult. If their system is strictly organized, keeping it organized requires significant effort and planning on the user’s part. On average, this tends to be a moderately difficult task.

Our system would keep track of where each book is, so you can put them wherever you like – either maintaining a conventional organizational scheme on top of BiblioFile, or not. The task becomes easy.

3. Determining if you own a book, or if a borrowed book is in your possession

Currently, if you do own a book, determining that you do own it is as easy as retrieving it – that is, of moderate difficulty. However, if you don’t own the book, you have to go through your entire collection to make sure that it is not in your collection at all, as opposed to simply being present but out of place. In this case, the task becomes hard.

With our system, once a user has entered all her books into the system, she can know with confidence whether or not she already owns a book, simply by looking that book up using our interface. This task is now easy.

Interface Design:

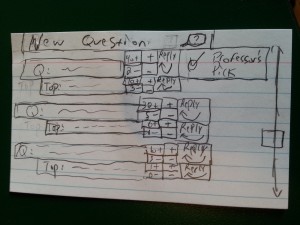

Provide a text description of the functionality of your system. What can a user do with it, and how?

Our system keeps track of a user’s books and their locations. A user can ask the system for the approximate location of a book, and the system will indicate where on the shelf it can be found. Additionally, a user could ask the system whether or not they own a particular book. We envision the user interacting with our system through a web application that lets them search for books as well as view all books in the collection. To add a book to the bookshelf system, we envision the user adding a physical “tag” to the book, which will then allow the book/tag combo to be automatically registered via our website.

2. What benefits does the application offer to the user? What is the scope of functions offered? How will your idea differ from existing systems or applications?

Our application allows the user to quickly find their books and determine what books they own without using rigid cataloging systems. Traditional organizational schemes are hard to maintain, and even harder to reconfigure. Our system allows users to place their books in any configuration within the special bookshelf, which gives the users more flexibility. Existing systems require the user to either adhere strictly to an organizational scheme such as Dewey Decimal, or to perform some specific action each time a book is moved (such as scanning a barcode).

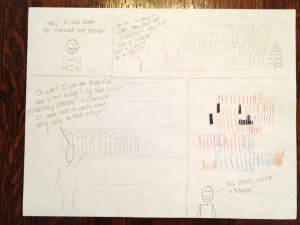

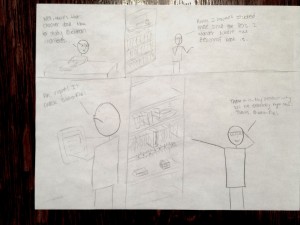

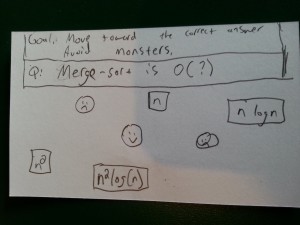

3. Provide 3 storyboards. Each one should show how someone would use your system to accomplish one of the three tasks you chose above. Show motivation for using the system, as well as steps the users will go through to accomplish the task.

Thanks to his Biblio-File system, this user is easily able to find and return his friend’s copy of Ender’s Game.

Freed from the constraints of a rigid organizational system, this user lets his imagination run wild!

Using his Biblio-File system, this scholar is able to quickly find the esoteric works he needs to conduct his research productively.

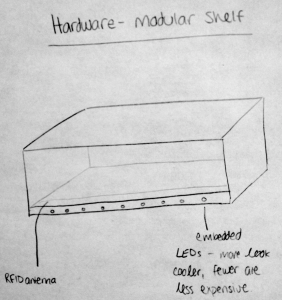

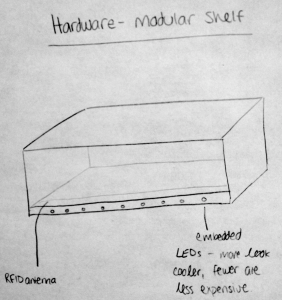

4. Provide a few sketches of the system itself. What might it look like? How might a user interact with it?

Hardware – Shelving: Our system will consist of one or more stacked modular shelves. Each shelf will contain an RFID sensor that will detect books contained within in, and transmit that information to the central server. It will also contain LED lights that will light up when a user selects a book in the software.

A modular shelving unit for BiblioFile

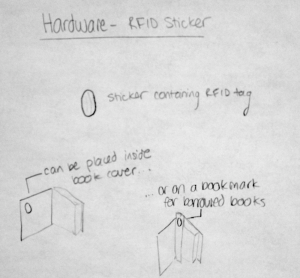

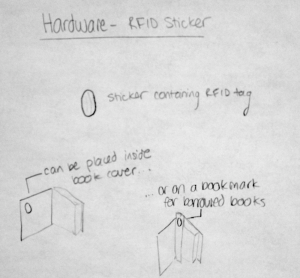

Hardware – RFID Stickers: The books’ presence will be sensed via RFID stickers that can be placed either inside a book (if the user owns the book) or on a bookmark that is placed inside the book (if the user does not own the book). These RFID tags can be disassociated with books after they are permanently removed from the collection and reused with other books.

Usage of the RFID stickers

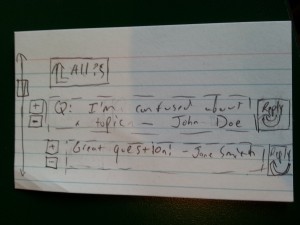

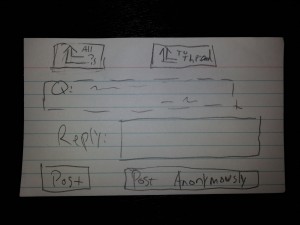

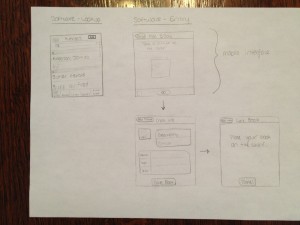

Software – Lookup: Using an interface similar to that of Music on iOS, users will be able to search the collection or browse by any of several types of metadata that the system tracks for each book. When they find the book they want, they tap its title, and its shelf will light up underneath its approximate location. To edit the collection (delete books), users tap the edit button.

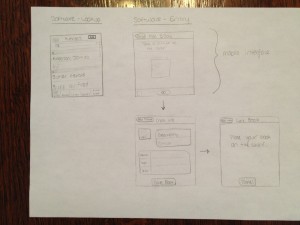

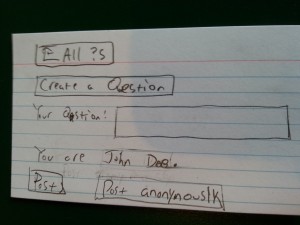

Software – Adding a Book: The system will initially try to use OCR to get the book’s information from the cover, after which the user will have the opportunity to edit or add information. The user then places the book on the shelf, so that the system knows which book is associated with which tag.

Interface mockup for looking up a book and for adding a new book to the collection

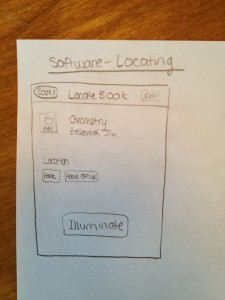

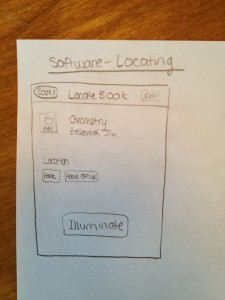

Software – Locating a Book: When a user taps on the book from the Lookup screen, she will be taken to a page containing the book’s information and tags associated with the location of the shelf that it is currently on. If the user desires, she may tap the illuminate button to have the shelf light up.

Interface mockup for locating a book in the collection