Princeton’s reunions are almost as old as Princeton University itself, going back to the days when the university was still known as the "College of New Jersey." In today’s blog, posted during the Reunions weekend of 2011, we are showing you the oldest reunion footage in the University Archives: an annotated film of the Class of 1895’s 20th and 30th Reunions in 1915 and 1925, followed by footage of the Class of 1915’s 40th Reunion in 1955, and the Class of 1944’s 65th Reunion in 2009, the most recent reunion footage in the University Archives. The films may be compared with reunion footage featured in previous blogs, including the Reunion of the Class of 1921 in 1923 and 1926, and the Reunions and P-rade of 1928, of 1960 and 1961, and of 1986. A compilation of this footage to welcome returning alumni in 2011 can be found here.

The Class of 1895’s 20th reunion footage is the first of its kind, and would well have been the very oldest film in the University Archives, if not for the newsreel footage of the inauguration of President John Grier Hibben in 1912. The film was made by the Connecticut Film Company, which had two men follow the class around campus on Reunions Saturday, then return the following Monday to show the film at the Class Dinner. As Class Secretary Andrew Imbrie put it in a letter to classmates in advance of Reunions, this would be “a stunt never before attempted at any Princeton reunion.”

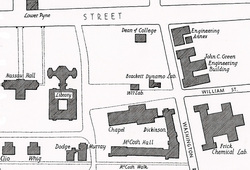

Back at headquarters at the Bachelor’s Club, we see a crowd of men and children gathered around class member Howard Colby’s “‘sarsaparilla automobile,’ built, decorated and provisioned with thoughtful consideration for the small army of sons and daughters” of class members (2:23). As the film winds down, the camera pans over the 136 class members who returned for 1895’s 20th along with their sons (3:53). The D.Q. Brown Long Distance Cup is presented by Dickinson Brown to his classmate Henry “Spider” McNulty, who traveled the farthest, from China, to attend the reunion.