(This is our ninth and final post about the films of diplomat John Van Antwerp MacMurray. See the first post for more background.)

“A typical group of Korean women gossiping on the road near Onseiri.” Postcard to Henrietta V.A. MacMurray, printed from a photograph by MacMurray (Box 26, December 4, 1928)

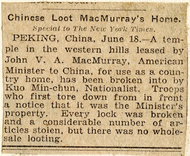

This is the last post featuring the films that diplomat John Van Antwerp MacMurray made while serving as Minister to China from 1925-1929. The film “The Diamond Mountains, 1928,” which captures a family vacation in Korea in the summer of 1928, may be a fitting end: in the three preceding years MacMurray had seen the country that he loved come under the control of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party, a development that he had watched with caution, as did many of his colleagues in the diplomatic corps. His thoughts about how to deal with the Nationalists differed from those of his superiors in Washington, which made his position increasingly difficult. On August 5, 1928, two months after the Nationalists took control of Peking, he wrote his mother about how much he and his wife were looking forward to the vacation in Korea. “Lois and I are feeling very “fed up” and stale and anxious to be away from things for long enough to take a fresh start.” The differences of opinion between MacMurray and his superiors, however, ultimately led to MacMurray’s resignation from his post in October 1929.

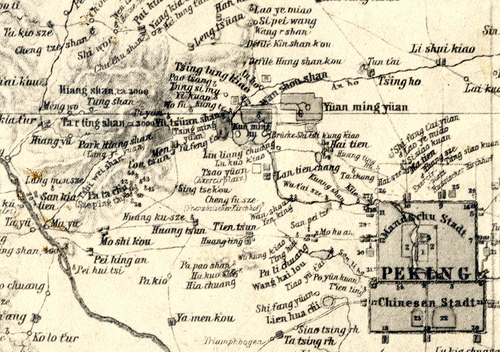

The family spent their vacation at one of the pools in the Diamond Mountains (Mount Geumgang, now North Korea), where they stayed in a hotel in the village of Onseiri in the Outer Kongo between August 17 and September 18, 1928. The film opens with family swimming, fishing, and mountain scenes, followed at 6:35 by brief footage of women on a street near Onseiri, also shown on the postcard above. The footage that follows of villagers and monks is assumed to be shot in the Choanji (Changansa) Monastery, which had the largest collection of temples in the Inner Kongo. MacMurray and his wife spent a few days there on their own, while their children were looked after at the hotel.

- MacMurray’s films of China, 1925-1929 (including “Kalgan”)

- Trip to attend the reinterment of Sun Yat-sen, 1929

- A diplomat’s trip along the Yangtze River, 1928

- Renting a temple in the Western Hills

- Marines and Chinese armies in Peking

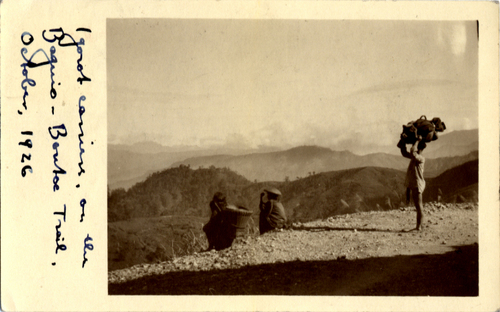

- Trips to the South and the Philippines, 1926 and 1929

- Vacation with the Navy, Friends with the Marines

- Peking friends and family scenes

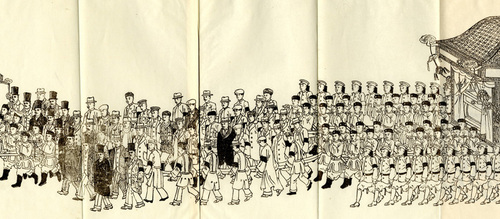

MacMurray, whose caricature is shown on the left, sent a copy to his chief Stanley Hornbeck, with the comment that Gallostra had a “genius for caricature and an irrepressible spirit of mockery” (19 July, 1929). In the film featured here, Gallostra, who is impersonating different characters, seems to be mimicking the prescribed behavior of the diplomatic representatives when paying their last respects to Sun Yat-sen. During a ceremony on May 31, prior to the reinterment, each minister placed a wreath at the foot of the dais at the headquarters of the Nationalist Party, where the embalmed body lay in state. The three bows while moving forward and backward can be found in descriptions of the ceremony. (Our thanks to Shuwen Cao, East Asian Library, Princeton University for clarifying this).

MacMurray, whose caricature is shown on the left, sent a copy to his chief Stanley Hornbeck, with the comment that Gallostra had a “genius for caricature and an irrepressible spirit of mockery” (19 July, 1929). In the film featured here, Gallostra, who is impersonating different characters, seems to be mimicking the prescribed behavior of the diplomatic representatives when paying their last respects to Sun Yat-sen. During a ceremony on May 31, prior to the reinterment, each minister placed a wreath at the foot of the dais at the headquarters of the Nationalist Party, where the embalmed body lay in state. The three bows while moving forward and backward can be found in descriptions of the ceremony. (Our thanks to Shuwen Cao, East Asian Library, Princeton University for clarifying this).