By Morgan Kelly, Office of Communications

The good news for any passionate supporter of climate-change science is that negative media reports seem to have only a passing effect on public opinion, according to Princeton University and University of Oxford researchers. The bad news is that positive stories don’t appear to possess much staying power, either. This dynamic suggests that climate scientists should reexamine how to effectively and more regularly engage the public, the researchers write.

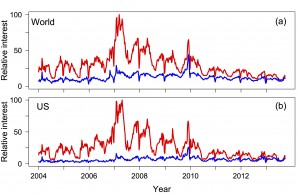

Measured by how often people worldwide scour the Internet for information related to climate change, overall public interest in the topic has steadily waned since 2007, according to a report in the journal Environmental Research Letters. Yet, the downturn in public interest does not seem tied to any particular negative publicity regarding climate-change science, which is what the researchers primarily wanted to gauge.

First author William Anderegg, a postdoctoral research associate in the Princeton Environmental Institute who studies communication and climate change, and Gregory Goldsmith, a postdoctoral researcher at Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, specifically looked into the effect on public interest and opinion of two widely reported, almost simultaneous events.

The first involved the November 2009 hacking of emails from the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, which has been a preeminent source of data confirming human-driven climate change. Known as “climategate,” this event was initially trumpeted as proving that dissenting scientific views related to climate change have been maliciously quashed. Thorough investigations later declared that no misconduct took place.

The second event was the revelation in late 2009 that an error in the 2007 Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — an organization under the auspices of the United Nations that periodically evaluates the science and impacts of climate change — overestimated how quickly glaciers in the Himalayas would melt.

To first get a general sense of public interest in climate change, Anderegg and Goldsmith combed the freely available database Google Trends for “global warming,” “climate change” and all related terms that people around the world searched for between 2004 and 2013. The researchers documented search trends in English, Chinese and Spanish, which are the top three languages on the Internet. Google Trends receives more than 80 percent of the world’s Internet search-engine activity, and it is increasingly called upon for research in economics, political science and public health.

Internet searches related to climate change began to climb following the 2006 release of the documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” starring former vice president Al Gore, and continued its ascent with the release of the IPCC’s fourth report, the researchers found.

Anderegg and Goldsmith specifically viewed searches for “climategate” between Nov. 1 and Dec. 31, 2009. They found that the search trend had a six-day “half-life,” meaning that search frequency dropped by 50 percent every six days. After 22 days, the number of searches for climategate was a mere 10 percent of its peak. Information about climategate was most sought in the United States, Canada and Australia, while the cities with the most searchers were Toronto, London and Washington, D.C.

The researchers tracked the popularity of the term “global warming hoax” to gauge the overall negative effect of climategate and the IPCC error on how the public perceives climate change. They found that searches for the term were actually higher the year before the events than during the year afterward.

“The search volume quickly returns to the same level as before the incident,” Goldsmith said. “This suggests no long-term change in the level of climate-change skepticism.

We found that intense media coverage of an event such as ‘climategate’ was followed by bursts of public interest, but these bursts were short-lived.”

All of this is to say that moments of great consternation for climate scientists seem to barely register in the public consciousness, Anderegg said. The study notes that independent polling data also indicate that these events had very little effect on American public opinion. “There’s a lot of handwringing among scientists, and a belief that these events permanently damaged public trust. What these results suggest is that that’s just not true,” Anderegg said.

While that’s good in a sense, Anderegg said, his and Goldsmith’s results also suggest that climate change as a whole does not top the list of gripping public topics. For instance, he said, climategate had the same Internet half-life as the public fallout from pro-golfer Tiger Woods’ extramarital affair, which happened around the same time (but received far more searches).

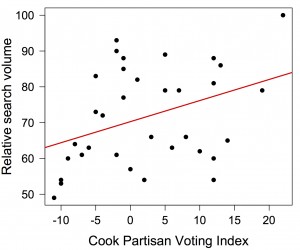

A public with little interest in climate change is unlikely to push for policies that actually address the problem, Anderegg said. He and Goldsmith suggest communicating in terms familiar to the public rather than to scientists. For example, their findings suggest that most people still identify with the term “global warming” instead of “climate change,” though the shift toward embracing the more scientific term is clear.

“If public interest in climate change is falling, it may be more difficult to muster public concern to address climate change,” Anderegg said. “This long-term trend of declining interest is worrying and something I hope we can address soon.”

One outcome of the research might be to shift scientists’ focus away from battling short-lived, so-called scandals, said Michael Oppenheimer, Princeton’s Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs. The study should remind climate scientists that every little misstep or controversy does not make or break the public’s confidence in their work, he said. Oppenheimer, who was not involved in the study, is a long-time participant in the IPCC and an author of the Fifth Assessment Report being released this year in sections.

“This is an important study because it puts scientists’ concerns about climate skepticism in perspective,” Oppenheimer said. “While scientists should maintain the aspirational goal of their work being error-free, they should be less distracted by concerns that a few missteps will seriously influence attitudes in the general public, which by-and-large has never heard of these episodes.”

Anderegg, William R. L., Gregory R. Goldsmith. 2014. Public interest in climate change over the past decade and the effects of the ‘climategate’ media event. Environmental Research Letters 9 054005. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/9/5/054005 Article published online May 20, 2014.

You must be logged in to post a comment.