To successfully infect its host, the rabies virus must move from the nerve ending to the nerve cell body where it can replicate. In a study published July 20 in the journal PLoS Pathogens, researchers from Princeton University reveal that the rabies virus moves differently compared to other neuron-invading viruses and that its journey can be blocked by a drug commonly used to treat amoebic dysentery.

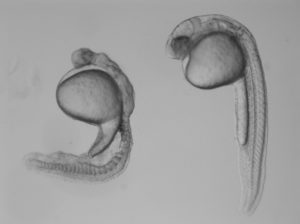

Most viruses only infect the nervous system accidentally when the immune system is compromised. But some “neurotropic” viruses have evolved to target neurons as part of their normal infectious cycle. The rabies virus, for example, is transmitted when an infected animal bites into a host’s muscle. It then spreads into the end terminals of motor neurons innervating the muscle and travels along the neurons’ long axon fibers to the neuronal cell bodies. From there, the virus can spread throughout the central nervous system and into the salivary glands, where it can be readily transmitted to other hosts. Though rabies infections in humans are rare in the United States, the virus kills nearly 60,000 people annually.

Alpha herpesviruses, such as herpes simplex viruses, also enter peripheral nerve terminals and move along axons to the neuronal cell body, where they can lie dormant for the life of the host.

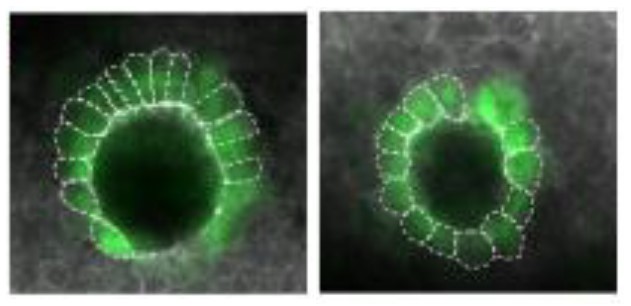

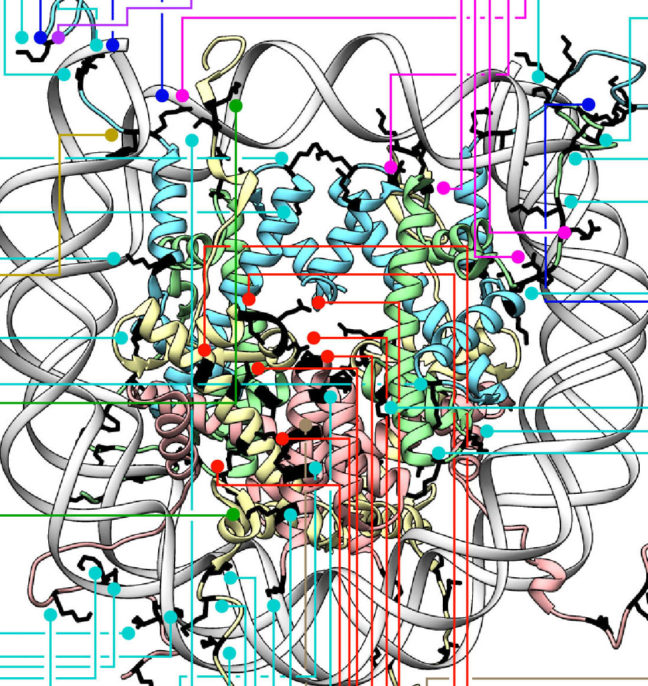

“Transport to the neuronal cell body is not a passive process, but an active one relying on the neuron’s own motor proteins and microtubule tracks,” said Lynn Enquist, Princeton’s Henry L. Hillman Professor in Molecular Biology, a professor of molecular biology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, and the study’s senior author. “Virus particles must engage this machinery for efficient transport in axons, otherwise infection cannot start.”

Enquist and colleagues previously found that alpha herpesviruses engage the neuronal transport machinery by stimulating protein synthesis at infected nerve terminals. Viral transport to the cell body can therefore be blocked by drugs that inhibit protein synthesis, as well as by cellular antiviral proteins called interferons.

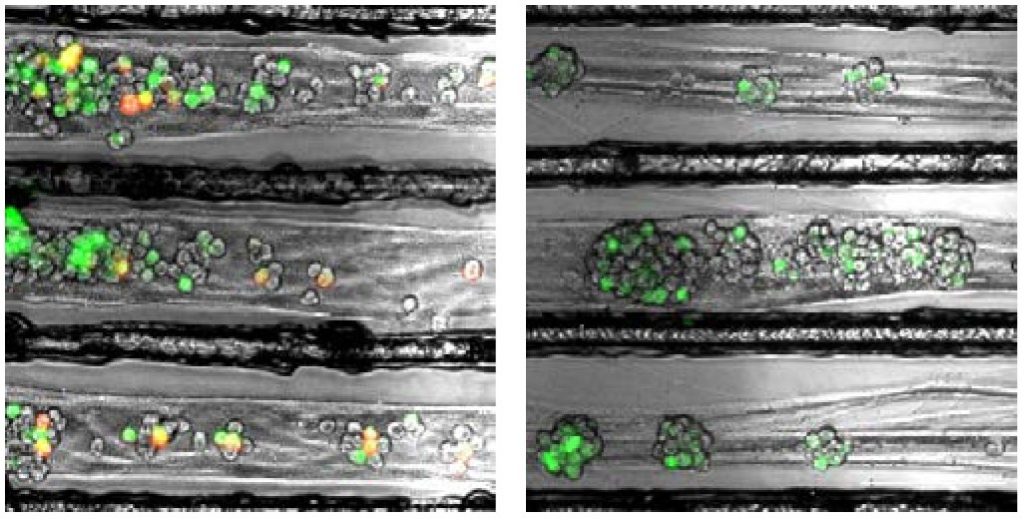

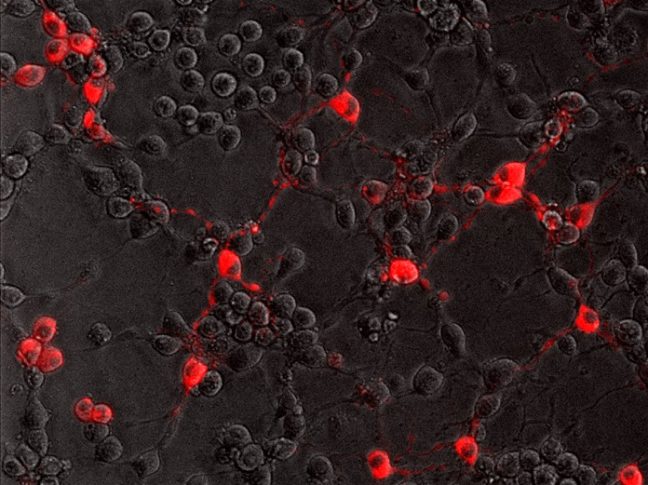

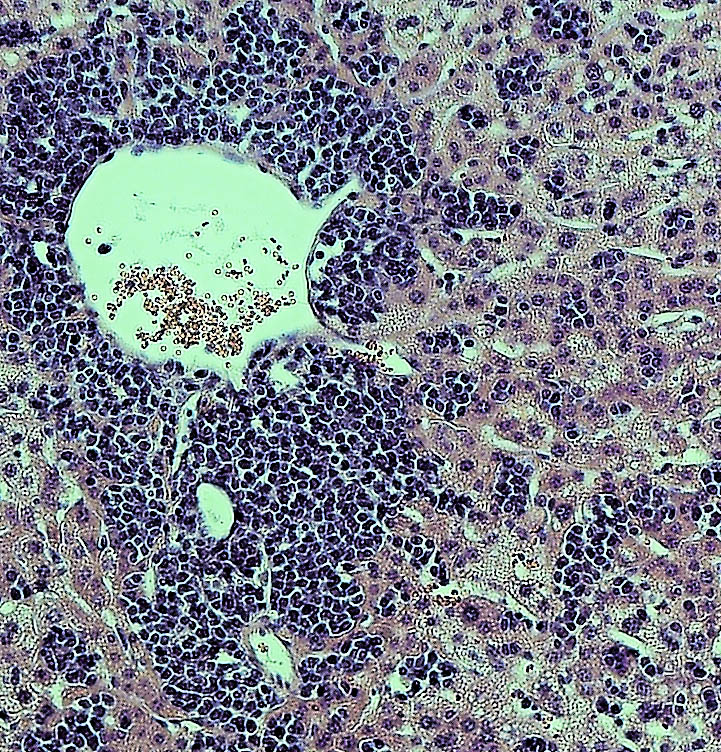

In the current study, Enquist and colleagues investigated how the rabies virus engages the neuronal transport machinery. The researchers infected neurons with a virulent strain of the virus tagged with a red fluorescent protein, allowing the researchers to observe viral transport in real time by live-cell fluorescence microscopy.

The study was led by Margaret MacGibeny, who earned her Ph.D. in 2018, and associate research scholar Orkide Koyuncu, at Princeton, with contributions from research associate Christoph Wirblich and Matthias Schnell, professor and chair of microbiology and immunology at Thomas Jefferson University.

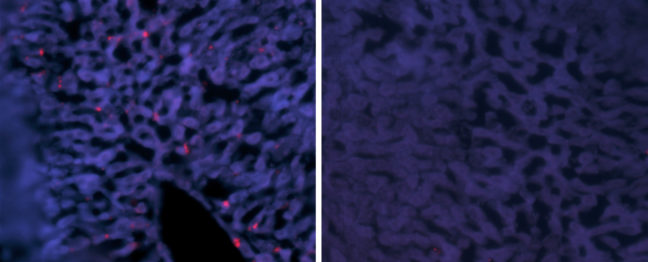

In contrast to alpha herpesvirus infections, the team found that interferons had no effect on rabies virus transport, perhaps because, until it reaches the neuronal cell body, the rabies virus hides out inside cellular structures called endosomes.

“We also couldn’t detect increased protein synthesis in axons upon rabies virus infection,” MacGibeny said. “But, to our surprise, we saw that a protein synthesis inhibitor called emetine efficiently blocked rabies virus transport to the cell body.”

Emetine had no effect on the transport of endosomes devoid of the rabies virus. But endosomes carrying the virus were either completely immobilized, or were only able to move short distances at slower-than-normal speeds.

Other protein synthesis inhibitors did not block rabies virus transport, however, suggesting that emetine works by inhibiting a different process in infected neurons.

“Emetine has been used to treat amoebic dysentery,” Koyuncu said. “In the laboratory it is widely used to inhibit protein synthesis but there are recent reports indicating that emetine has anti-viral effects that are independent of protein synthesis inhibition. Our study shows that this drug can inhibit rabies virus invasion of the nervous system through a novel mechanism that hasn’t been reported before.”

“The manuscript by MacGibeny et al. both advances and complicates our understanding of how neurotropic viruses make their way from the axon terminus to the cell body,” said Professor Glenn Rall, an expert in neurotropic virus infections at Fox Chase Cancer Center, who was not involved in the study. “Revealing variations in the axonal transport of neurotropic viruses, coupled with intriguing insights into new roles for well-known drugs, has both mechanistic and clinical implications for these life-threatening infections.

“Our next step is to figure out how emetine disrupts rabies virus transport in axons,” Enquist says. “Does it inhibit cell signaling pathways after rabies virus entry, or does it directly block the recruitment of motor proteins to virus-carrying endosomes?”

This study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (grants P40 OD010996, RO1 NS33506, and F30 NS090640).

The study, Retrograde axonal transport of rabies virus is unaffected by interferon treatment but blocked by emetine locally in axons, by Margaret A. MacGibeny, Orkide O. Koyuncu, Christoph Wirblich, Matthias J. Schnell, and Lynn W. Enquist was published in PLoS Pathogens. 2018. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007188

Text courtesy of the Department of Molecular Biology

You must be logged in to post a comment.