By Catherine Zandonella, Office of the Dean for Research

A study published today in the journal Science found that government biofuel policies rely on reductions in food consumption to generate greenhouse gas savings.

A study published today in the journal Science found that government biofuel policies rely on reductions in food consumption to generate greenhouse gas savings.

Shrinking the amount of food that people and livestock eat decreases the amount of carbon dioxide that they breathe out or excrete as waste. The reduction in food available for consumption, rather than any inherent fuel efficiency, drives the decline in carbon dioxide emissions in government models, the researchers found.

“Without reduced food consumption, each of the models would estimate that biofuels generate more emissions than gasoline,” said Timothy Searchinger, first author on the paper and a research scholar at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and the Program in Science, Technology, and Environmental Policy.

Searchinger’s co-authors were Robert Edwards and Declan Mulligan of the Joint Research Center at the European Commission; Ralph Heimlich of the consulting practice Agricultural Conservation Economics; and Richard Plevin of the University of California-Davis.

The study looked at three models used by U.S. and European agencies, and found that all three estimate that some of the crops diverted from food to biofuels are not replaced by planting crops elsewhere. About 20 percent to 50 percent of the net calories diverted to make ethanol are not replaced through the planting of additional crops, the study found.

The result is that less food is available, and, according to the study, these missing calories are not simply extras enjoyed in resource-rich countries. Instead, when less food is available, prices go up. “The impacts on food consumption result not from a tailored tax on excess consumption but from broad global price increases that will disproportionately affect some of the world’s poor,” Searchinger said.

The emissions reductions from switching from gasoline to ethanol have been debated for several years. Automobiles that run on ethanol emit less carbon dioxide, but this is offset by the fact that making ethanol from corn or wheat requires energy that is usually derived from traditional greenhouse gas-emitting sources, such as natural gas.

Both the models used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the California Air Resources Board indicate that ethanol made from corn and wheat generates modestly fewer emissions than gasoline. The fact that these lowered emissions come from reductions in food production is buried in the methodology and not explicitly stated, the study found.

The European Commission’s model found an even greater reduction in emissions. It includes reductions in both quantity and overall food quality due to the replacement of oils and vegetables by corn and wheat, which are of lesser nutritional value. “Without these reductions in food quantity and quality, the [European] model would estimate that wheat ethanol generates 46% higher emissions than gasoline and corn ethanol 68% higher emissions,” Searching said.

The paper recommends that modelers try to show their results more transparently so that policymakers can decide if they wish to seek greenhouse gas reductions from food reductions. “The key lesson is the trade-offs implicit in the models,” Searchinger said.

The research was supported by The David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

T. Searchinger, R. Edwards, D. Mulligan, R. Heimlich, and R. Plevin. Do biofuel policies seek to cut emissions by cutting food? Science 27 March 2015: 1420-1422. DOI: 10.1126/science.1261221.

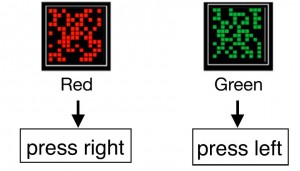

Sometimes being too focused on a task is not a good thing.

Sometimes being too focused on a task is not a good thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.