by Tien Nguyen, Department of Chemistry

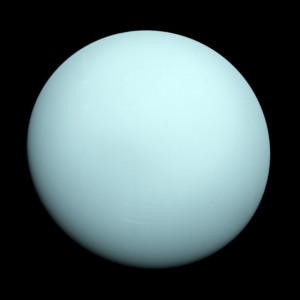

Scientists have predicted a new phase of superionic ice, a special form of ice that could exist on Uranus and Neptune, in a theoretical study performed by a team of researchers at Princeton University.

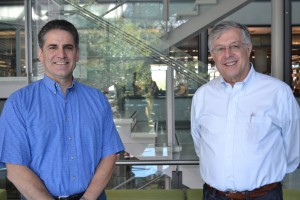

“Superionic ice is this in-between state of matter that we can’t really relate to anything we know of — that’s why it’s interesting,” Salvatore Torquato, a Professor of Chemistry who jointly led the work with Roberto Car, the Ralph W. ‘31 Dornte Professor in Chemistry. Unlike water or regular ice, superionic ice is made up of water molecules that have dissociated into charged atoms called ions, with the oxygen ions locked in a solid lattice and the hydrogen ions moving like the molecules in a liquid.

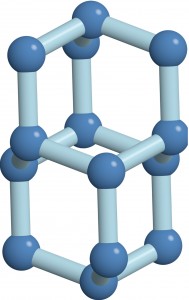

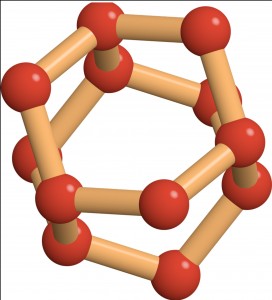

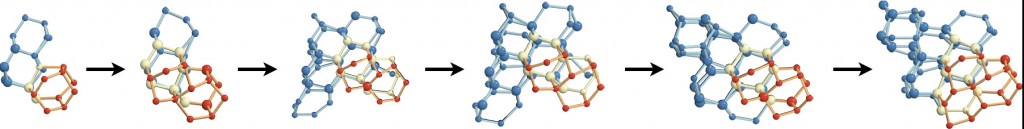

Published on August 28 in Nature Communications, the research revealed an entirely new type of superionic ice that the investigators call the P21/c-SI phase, which occurs at pressures even higher than those found in the interior of the giant ice planets of our solar system. Two other phases of superionic ice thought to exist on the planets are body-centered cubic superionic ice (BCC-SI) and close-packed superionic ice (CP-SI).

Each phase has a unique arrangement of oxygen ions that gives rise to distinct properties. For example, each of the phases allows hydrogen ions to flow in a characteristic way. The effects of this ionic conductivity may someday be observed by planetary scientists in search of superionic ice. “These unique properties could essentially be used as signatures of superionic ice,” said Torquato. “Now that you know what to look for, you have a better chance of finding it.”

Unlike Earth, which has two magnetic poles (north and south), ice giants can have many local magnetic poles, which leading theories suggest may be due to superionic ice and ionic water in the mantle of these planets. In ionic water both oxygen and hydrogen ions show liquid-like behavior. Scientists have proposed that heat emanating outward from the planet’s core may pass through an inner layer of superionic ice, and through convection, create vortices on the outer layer of ionic water that give rise to local magnetic fields.

By using theoretical simulations, the researchers were able to model states of superionic ice that would be difficult to study experimentally. They simulated pressures that were beyond the highest possible pressures attainable in the laboratory with instruments called diamond anvil cells. Extreme pressure can be achieved through shockwave experiments but these rely on creating an explosion and are difficult to interpret, Professor Car explained.

The researchers calculated the ionic conductivity of each phase of superionic ice and found unusual behavior at the transition where the low temperature crystal, in which both oxygen and hydrogen ions are locked together, transforms into superionic ice. In known superionic materials, generally the conductivity can change either abruptly (type I) or gradually (type II), but the type of change will be specific to the material. However, superionic ice breaks from convention, as the conductivity changes abruptly with temperature across the crystal to close-packed superionic transition, and continuously at the crystal to P21/c-SI transition.

As a foundational study, the research team investigated superionic ice treating the ions as if they were classical particles, but in future studies they plan to take quantum effects into account to further understand the properties of the material.

Read the article here:

Sun, J.; Clark, B. K.; Torquato, S.; Car, R. “The phase diagram of high pressure superionic ice.” Nature Communications, Published online August 28, 2015.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (DMS-1065894) and the US Department of Energy (DE-SC0008626 and DE-SC0005180).

You must be logged in to post a comment.