La Coquille et le Clergyman (1928)

Germaine Dulac’s La Coquille et le Clergyman was the very first surrealist film, influencing many later productions, including Buñuel and Dali’s celebrated Un Chien Andalou. It explores the duality between the dream and the cinematic image, and thus draws a parallel between the latter and the exploration of the unconscious. In understanding the important elements behind the movie, it is imperative to consider her relationship with the original scriptwriter, Antonin Artaud. The notorious initial screening of the film, which almost erupted into conflict between the audience and Dulac, has played a great role in highlighting the differences between the visions of Dulac and Artaud in their understanding of visual language. An analysis of these differences requires reference to the dream aesthetic, especially in connection to the way that surrealist film in particular strove to represent its connections with the subconscious.

Germaine Dulac, director of La Coquille et le Clergyman

For Dulac, the film represented a chance to break free from the constraints of the traditional narrative found in film and literature. This can be observed in how the film’s scenario progresses based solely on visual cues, with a lack of on-screen dialogue contributing heavily to a dream-like construction. Indeed, the swift movement between scenes that ostensibly represent reality to ones that cannot but be imaginary greatly adds to this notion. For example, the scenes depicting the journey of the general and his wife in the streets of Paris, when the clergyman first sees her and is infatuated, clash harshly with scenes like that of the clergyman’s pursuit of the same woman through the woods, with his stiff zombie-like posture connoting that this scene could not possibly be real but is instead part of a dream sequence. Additionally, the continual use of cinematographic techniques, such as the sudden immolation of the seashell or the continual blurring of the protagonists’ faces demonstrates a direct desire on the part of the director to ‘reconstruct’ the clergyman’s dream. The periphery of many shots is also blurred at times, further indicating a dream-like nature. All of this is compounded by the heavy usage of point-of-view shots, which result in the audience observing the action through the eyes of the clergyman. This has a major effect on the film’s interpretation by the audience. Indeed, the point-of-view angle mirrors the way many people have dreams, focusing here in the experience of the clergyman and underscoring that the action is personalized to his experience.

However, Artaud’s script is also important for a robust interpretation of the film. More specifically, his contention that this “is not a reproduction of a dream” [3] alongside the notion that one cannot reproduce dreams, since reproduction would invariably alter them, go a long way in conflating Artaud’s ideal to Desnos’, who hoped that “film-makers record and reconstruct their dreams”[4] instead, drawing a distinction between reconstruction and reproduction. For Artaud, the main objective of his experimentation with film lay in the development of a medium of expression not based on language but which “would not only express, but also … be the very flesh and blood of his thought”.[5] This foray into the subconscious can be observed in the symbolism that can be attributed to the different characters, most notably the woman protagonist and the general. Indeed, the general’s power over the clergyman, epitomized almost instantaneously through his overtly shining sword and confirmed when he breaks the clergyman’s seashell, come to make the clergyman’s sexual interests in the general’s wife take on a different meaning. Although he is sexually interested in her, as observed in his lustful removal of her clothing, the fact that her breasts transform into the seashell which then burns violently brings forth a strong link between his emasculation by the general and his pursuit of her.

As the clergyman’s insanity progresses throughout the movie, his attempts at and fantasies of removing the general become more and more violent.

Furthermore, his complete lack of empathy for her further shows an obsession with his position of powerlessness, for she becomes but a symbolic object of desire rather than an individual. The fact that he feels inferior to the general urges the clergyman to take from him what he holds dearest, which is what fuels his desire for the woman throughout the movie. Indeed, his desire for the general’s wife can be underscored in his ever-growing boldness in trying to capture her, which culminates not in sexual climax but rather in him entrapping her in a glass vase. The fact that at the end of the movie she turns into the clergyman when the vase breaks demonstrates that it was the clergyman’s emasculation vis-a-vis the general and his subconscious that played a strong role in driving him this far into ever-growing insanity.The fact that the woman turns into the clergyman shows that he was not really after her – the root of his desire for her was in fact his obsession with the general’s power over him.

Finally, this inherent desire for a certain object, alongside the purposefully blurred boundaries between reality and fantasy, are signature elements of surrealism. Indeed, the “surrealist pursues objects … and seeks to form a whole with them”, [1] a notion faithfully observed in the clergyman’s relentless desire for the woman. The final scenes depicting the two together, where the woman first turns into the clergyman and then into liquid, underscore how the two become one, since the protagonist then drinks the liquid, finally satisfying his pursuit by ‘becoming one’ with the object of his desire.[2] This final scene is indicative of Dulac’s interest in making the audience experience the movie from the point of view of both the man and the woman, thus allowing the viewer to understand the rigidity of their gender roles.

[1] Michael Gould, Surrealism and the Cinema: (open-eyed screening) (Cranbury: A. S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1976) p. 21-2

[2] Sandy Flitterman-Lewis, “The Image and the Spark: Dulac and Artaud Reviewed,” Dada and Surrealist Film, Rudolf E. Kuenzli, Ed. (New York: Willis Locker and Owens, 1987)

[3] Alain and Odette Virmaux, Artaud/Dulac La Coquille et Le Clergyman: Essai D’Élucidation D’une Querelle Mythique, trans. Tami Williams (Paris: Éditions Paris Expérimental, 1999) p. 104

[4] Linda Williams, Figures of Desire: A Theory and Analysis of Surrealist Film. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981) p. 20

[5] Id.

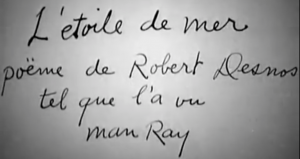

L’Etoile de mer (1928)

L’Etoile de mer: Poëme de Robert Desnos tel que l’a vu Man Ray (poem by Robert Desnos as interpreted by Man Ray) is a 15 minute movie made by a collaboration between Man Ray and Desnos in 1928. The film is inspired and structured by a poem of the same name by Desnos, which has been until recently considered lost. The poem’s text is inseparable from the film, and vice versa, earning the film the classification of ciné-poème. According to accounts by Man Ray, he heard the poem at a farewell dinner for Desnos, who was about to embark on a trip. Man Ray was so moved that by the time Desnos returned to France, the film was completed. More recent accounts, as well as reports by Desnos and found screenplays (see below) prove that Desnos had more of a hand in the creation of the film; although he was away for most of the filming, he was heavily involved in both the writing of the screenplay and in technical aspects of the filming.[1] In the end, both filmmakers were happy with the result, with Desnos stating Man Ray granted him “the most flattering and moving image of [himself] and of [his] dreams.”[2] This film is quite different from Man Ray’s previous films, which have nearly no narrative structure. In addition, his previous films belonged to the Dada tradition, in which there is an insurmountable distance between the viewer and the world created by the film. L’etoile de mer, as is the tradition with Surrealist artwork, actively invites the viewer to participate in the created surreality; the film starts with the literal opening of a window, and ends with it closing, returning the viewer to the real world.

The poem was inspired by an actual sea-star that Desnos owned as well as by his unrequited love for a woman, Yvonne George. The film’s protagonist, played by André de la Rivière, also faces the struggles of being in love with a woman (Kiki de Monparnasse). It opens with a scene of a woman and a man walking in a park, where we first notice the visual blur that characterises the film, made by a gelatinised lens that Man Ray used to shoot the film.

The film alternates between blurred and normal vision. We do not see the woman’s face or whole body in focus, only through the filter. What we do see

Blurry shots from the gelatinized lens.

clearly are small parts of her: a hand, a foot, a thigh. The filter, possibly originally intended to avoid censorship in the scene where the woman takes off her clothes, creates an erotic and dream-like feeling to the film. During the opening scenes in the bedroom, the protagonist sits there stoically, strangely indifferent to the very naked woman lying next to him. The viewer is inclined to strain the vision to see behind the filter. This is futile, though, since there is either nothing sexual to see or nothing that can be seen behind the filter, so the viewer is forced into the passive position of a dreamer. The erotic is treated in a humorous manner – these opening scenes lead us to expect sexuality, which would have been rather shocking and unexpected of cinema at the time, and instead we are very surprised to not find it.

From the first intertitle, “Les dents des femmes sont des objets si charmantes, qu’on ne devrait les voir qu’en rêve ou a l’instant de l’amour” the audience gets the impression that the woman is something to be approached with caution. It is only safe to see her when she is ‘powerless’ – either in a dream, or when she has succumbed to love. In fact, the only shot we see of the woman without the filter is of her sleeping, in her own dream, unable to harm. After the protagonist leaves the woman in the bedroom, we see the inter-title “Si belle! Cybele?”  The sound of this line recalls the repetition of sounds characteristic to Desnos’ poetry. Indeed, there are many instances where the inter-titles play with similar sounds and sentence structures. Most importantly, the woman, for her beauty, is associated with Cybele, the Phyrgian mother goddess. Cybele in turn is associated with castration (perhaps due to the threat of a woman’s teeth, as seen before), as all of her male attendants had to castrate themselves. For a man to to have a relationship with a woman, it seems he must suffer.

The sound of this line recalls the repetition of sounds characteristic to Desnos’ poetry. Indeed, there are many instances where the inter-titles play with similar sounds and sentence structures. Most importantly, the woman, for her beauty, is associated with Cybele, the Phyrgian mother goddess. Cybele in turn is associated with castration (perhaps due to the threat of a woman’s teeth, as seen before), as all of her male attendants had to castrate themselves. For a man to to have a relationship with a woman, it seems he must suffer.

Nearing the end of the film, the female protagonist is now explicitly menacing – she holds a knife, and her image is associated with fire (une fleur de feu, as the inter-title says). We then see her dressed in a robe and a Phrygien bonnet, again recalling Cybele and her threat to manhood, castration.

Despite all the animosity and fear she generates, there is still an attraction to her, a desire to understand and, most importantly, control the woman. This impossibility of possessing the feminine ideal is resolved by the introduction of the figure of the sea star. The woman is merely a means to an end of incorporating the feminine Surrealist sensibility into the man. As the film progresses, the importance of the starfish rises, while that of the woman lowers until she is eventually rejected.

The transition is first evident around the middle of the film, after the protagonist has acquired the sea star . We see a collage of shiny, spinning apparatuses and glass objects, including the sea star in a glass jar. The protagonist has started to replace his love for the woman with an obsession with the sea star. This scene is unfiltered; we get the impression that it is as easy for us to see the sea star as it is for the man to understand it, as opposed to the woman. An inter-title repeats (Si les fleurs etaient en verre), followed by a blurry shot of the woman. Already the man wishes for the woman, who is repeatedly described as a flower, to be as beautiful and transparent as crystal. The muddled, dreamy vision becomes completely associated with the woman, juxtaposed with the clarity of the shots of the sea star.

. We see a collage of shiny, spinning apparatuses and glass objects, including the sea star in a glass jar. The protagonist has started to replace his love for the woman with an obsession with the sea star. This scene is unfiltered; we get the impression that it is as easy for us to see the sea star as it is for the man to understand it, as opposed to the woman. An inter-title repeats (Si les fleurs etaient en verre), followed by a blurry shot of the woman. Already the man wishes for the woman, who is repeatedly described as a flower, to be as beautiful and transparent as crystal. The muddled, dreamy vision becomes completely associated with the woman, juxtaposed with the clarity of the shots of the sea star.

Glass becomes associated with the sea star.

The inter-title “Belle, belle, comme une fleur de verre” (beautiful like a glass flower – implying it is delicate, non-threatening and eternal) is followed by an image of the sea star, whilst the inter-title “Belle, belle, comme une fleur de chair” (beautiful like a lower made of flesh) is associated with an image of the woman, making her unappealing and, most importantly, ephemeral. The similarity of the lines of the poem, both in structure and in sound, serve both to make the sea star and the woman one being and to emphasise the preferability of the sea star. The perception of the ideal woman, which was in reality an illusion, as a woman is human and therefore ever-changing and complex, becomes tangible in the sea star. It is as though the protagonist has distilled all of the preferable aspects of a woman (such as beauty and delicateness) into the sea star, and has left to the woman those which posed a threat to him (like her changing whims or individual desires).

At the end of the film, the couple is seen walking in the park, where another man (played by Desnos himself) comes and takes the woman away. But the man does not despair – he still possesses the sea star. An inter-title reads “Qu’elle était belle” (she was beautiful), followed by a shot of the woman, while the following one parallels it, “Qu’elle est belle” (she is beautiful), followed by a shot of the sea star. The woman herself is abandoned, replaced by a permanent ideal object that will never disappoint or threaten the protagonist. The last scene of the film is quite a shock – we see the woman looking at herself in the mirror, but it seems almost as though she is behind a glass that reads belle, which then shatters. The woman, powerful and threatening, cannot be kept under glass like the sea star can.

In his work Dada and Surrealist film, Robert Kuenzli summaries the relationship between male Surrealists and women:

“The Surrealist quest must not be seen as the search for an ideal ‘other’ or yet another instance of the idealisation of the woman, but rather as the (admittedly narcissistic) goal of incorporating the womanly into the male persona”.

As in Breton’s Nadja, the Surrealist male is constantly in pursuit of what he perceives to be the ideal woman. To do so, though, will only lead to suffering and anxiety; the reality is that the ideal Surrealist woman would be like Leonora Carrington – probably insane. To remedy this, to further “incorporate the womanly” into their male persona, the woman must either be demystified and rejected, only to be revisited in dreams or memories, or else preserved in another way – by art, literature, poetry or in sea stars under glass.

[1] Rudolf E. Kuenzli, ed., Dada and Surrealist Film (New York: Willis, Locker & Owens, 1987), 208.

[2] Ibid.

Un Chien andalou (1928) and L’age d’or (1930)

Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L’Age D’Or (1930) are widely considered to be the staples of Surrealist film by most scholars of surrealism. Writer Linda Williams attributes this to the generation of young Surrealists living in the 1950s who attempted to “formulate a canon of the Surrealist and surrealistic film (200).” Thus those who considered themselves to be surrealists or scholars of surrealism became just as concerned, if not more concerned, with creating a working definition of what surrealism and surrealist film was as the founders of the movement like André Breton and the makers of the films themselves. Surrealist scholar Haim Finkelstein points out in his essay “Dali and Un Chien Andalou: The Nature of a Collaboration,” that Dalí and Buñuel’s collaboration on these two films was not as straightforward as it may appear. He argues that today, Buñuel is given most of the credit for the “positive values” of the films whilst Dalí is either underrepresented or blamed for more negative aspects of the film (128). The “positive values” that Finkelstein is referring to are most likely the depiction of what most would argue to be surrealist ideals and the surrealist worldview. Yet, before the making of Un Chien Andalou, neither Dalí nor Buñuel made much reference to Surrealism in their writings (129).

According to both of the filmmakers, the film was inspired by dreams Buñuel and Dalí had had which featured the cutting open of an eye and ants crawling out of the palm of a hand respectively (Adamowicz, 2). The two then collaborated on writing the script through automatic writing (Adamowicz, 2). Thus, the film was inspired by surrealism in its creation. The film was then shot in two weeks and final production and editing were rushed (Adamoqicz,13). It then premiered in Studio des Ursulines on June 6,1929 at an exhibition held by prominent Surrealist artist Man Ray (Adamoqicz, 16). Audiences were generally shocked by some of the violent imagery in the film, but reception to the film was not as hostile or scandalous as many would have thought. Film historian Elza Adamowicz argues that the film often associated with the scandalous reception of Buñuel’s later film L’Age D’Or (17). Despite what some may have called a hostile reception, it is the premiere of this film that truly established Buñuel and Dalí as part of the in-crowd of Surrealist with regular meetings thereafter with André Breton (Adamowicz, 18).

Finkelstein compares Un Chien Andalou to Artaud’s La Coquille et le Clergyman. Artaud seems to employ cinematic techniques so as to make rational and consistent transitions and to follow a more specific storyline. As Finklestein describes “there is no sense of dislocation or discontinuity, everything is fully resolved by the miracle of cinema (132).” In Un Chien Andalou, “dislocations and disruptions of space and of narrative continuity are matter-of-factly and naturally presented as if requiring no further validation (132).” Finkelstein provides many examples of how the film goes through the process of subverting the norms of mainstream cinema as with the seemingly random inter titles indicating time which usually provide continuity and narrative but instead further confuse and disrupt any semblance of a narrative. Un Chien Andalou as a whole features seemingly random images and sequences that, nonetheless, serve to convey the more prominent Surrealist themes of castration anxiety, sexual desire, religion, Freudian psychological concerns, and dreams. The most famous scene of the film which depicts the cutting of the eye of the lead female protagonist is argued by many scholars to in someway reflect the Surrealist preoccupation with all the themes previously mentioned (Finkelstein, 133).

Whereas Surrealist scholars tend to point out the many ways in which the narrative, plot structure, development of characters, relationship between time and space, and editing are particularly unusual, Buñuel’s and Dalí’s later film, L’Age D’Or, became his first foray into the realm of mainstream cinema whilst also infusing highly Surrealist themes into the film. Production of the film was difficult given budget and filming constraints, but L’Age D’Or is known more widely today for its quite hostile reception and the many scandals associated with its premiere (Gubern, 24). The film interestingly combines elements of speaking and silent films, and addresses the issues of sexual desire, the Church/religion, and the corrupt life of the bourgeoisie especially when compared to their treatment of the working class. The film, was seen as somewhat of a satire of the Italian government and of the Catholic Church, as such it was embroiled in multiple censorship controversies with the Parisian Ministry of State Education and Fine Arts and the right-wing Ligue des Patriotes (Gubern, 53). Viewers were shocked, and often appalled by the film’s depiction of the Catholic Church, sex, and the films many calls rather direct calls for revolution and it would not be commercially released until the 1980s (Gubern, 86).

Thus, both Un Chien Andalou and L’Age D’Or are regarded as the most authentic of surrealist films given the attention given to the surrealist ideals of dreams, illusion, reality, materiality, and the exposing of the corruption of the strong governing institutions of the time, in addition to the Surrealist affiliations that Buñuel and Dalí acquired over time.

Adamowicz, Elza. Chien Andalou : French Film Guide. London: I.B. Tauris, 2010.

Gubern, Román, and Hammond, Paul. Luis Buñuel: The Red Years. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

Willams, Linda. The Critical Grasp: Buñuelian Cinema and Its Critics.

Finkelstein, Haim. Un Chien andalou: The Nature of a Collaboration.

The Manifesto concerning L’Age d’or (1930)

Accompanying the release of Luis Buñuel’s film L’Age d’or members of the Surrealist group wrote and published the “Manifesto of the Surrealists concerning L’age d’or”. The manifesto is an incredibly dense text broken up in to seven sections: a short introduction, “The sexual instinct and death instinct,” “It’s the mythology that changes,” “The gift of violence,” “Love and disorientation,” “Situation in time,” and “Social aspect—subversive elements”. These categories cover the aims of Surrealist art making with respect to film, considerations of themes that drive Surrealist film (i.e. sex, love, violence), the relationship of Surrealist film to myth and the intended audience and reception of L’age d’or. The film is referred to by the group as “one of the most extensive set of demands to human consciousness to this day,” and the manifesto itself demands much of the reader to understand it’s musings on that consciousness.[1]

Art making, including the making of films, is not about the end product. Instead, it is about exploring the origins of the “sublimated energy” within the artist, an energy which is muzzled by the “existing order of things,” and loosening that muzzle. In the Surrealists words it is, “To give in, with all the cynicism this enterprise entails, to the tracking down within oneself and the affirmation of all the hidden tendencies of which the artistic end product is merely an extremely frivolous aspect.”[2] They go on to identify two of those “hidden tendencies” of particular importance—the “sexual instinct” and the “death instinct”. These two instincts seem to stem from Freud’s “pleasure principle” and “death drive,” though no mention of Freud is made in the manifesto (citation Beyond The Pleasure Principle???). The sexual instinct, they claim, is better at “sustaining the spirit’s light,”[3] though they also grant that one is only possible in the presence of the other.

Myths are not the residue of primitive taboos. The destruction of this system of myths coexists with the possibility of rediscovering archaic myths that prove that certain symbolic constants exist in unconscious thought, that this thought is “independent of every mythic system.”[4] However, the Surrealists maintain that these myths change, divined as a result of a collective transference caused by ambivalence (in the Freudian sense).

The manifesto goes on to discuss the gift of violence, that anger which comes as a result of being the victim of confusion, as well as love and disorientation, corresponding to the “bankruptcy of feelings” in capitalist society, and a public always searching for new conventions by which to liberate themselves. In L’Age d’or, on the other hand, they claim that “Buñuel has formulated a theory of revolution and love that goes to the very core of human nature.”[5]

The manifesto ends with a discussion of the audience and the envisioned reception of the film. The group expresses concern that surrealist thought will be harnessed toward the wrong end, that people will take it as “grist for [their] mill,” as a tool in their own agendas: “whatever fence we put around a seemingly well-protected estate, we can be sure it will immediately be covered in shit.”[6] This prediction was proven true, at least in some sense, as the film was received with rage in some circles and was banned after just two weeks in theaters. The ideal audience of the Surrealist work, then, is neither those who are unreceptive, nor those who co-opt the work, but a like-minded individual: “let’s give way, therefore, to that man… indifferent to all that does not uniquely concern the love occupying him… this world he is not on terms with and to which, once again, we belong only to the degree we protest against it.”[7] The positioning of that individual in society leads the broader goal of the film itself: “the social value of L’age d’or must be establish by the degree to which it satisfies the destructive needs of the oppressed.”[8]

hi