Infectious diseases kill millions of people each year, but the search for treatments is hampered by the fact that laboratory mice are not susceptible to some human viruses, including killers like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). For decades, researchers have turned to mice whose immune systems have been “humanized” to respond in a manner similar to humans.

Now a team at Princeton University has developed a comprehensive way to evaluate how immune responses of humanized mice measure up to actual humans. The research team looked at the mouse and human immune responses to one of the strongest vaccines known, a yellow fever vaccine called YFV-17D. The comparison of these “vaccine signatures” showed that a newly developed humanized mouse developed at Princeton shares significant immune-system responses with humans. The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

“Understanding immune responses to human pathogens and potential vaccines remains challenging due to differences in the way our human immune system responds to stimuli, as compared to for example that of conventional mice, rats or other animals,” said Alexander Ploss, associate professor of molecular biology at Princeton. “Until now a rigorous method for testing the functionality of the human immune system in such a model has been missing. Our study highlights an experimental paradigm to address this gap.”

Humanized mice have been used in infectious disease research since the late 1980s. Yet without rigorous comparisons, researchers know little about how well the mice predict human responses such as the production of infection-fighting cells and antibodies.

To address this issue, researchers exposed the mice to the YFV-17D vaccine, which is made from a weakened, or attenuated, living yellow fever virus. Vaccines protect against future infection by provoking the production of antibodies and immune-system cells.

In previous work, the researchers explored the effect of YFV-17D on conventional humanized mice. But the researchers found that the mice responded only weakly. This led them to develop a mouse with responses that are more similar to those of humans.

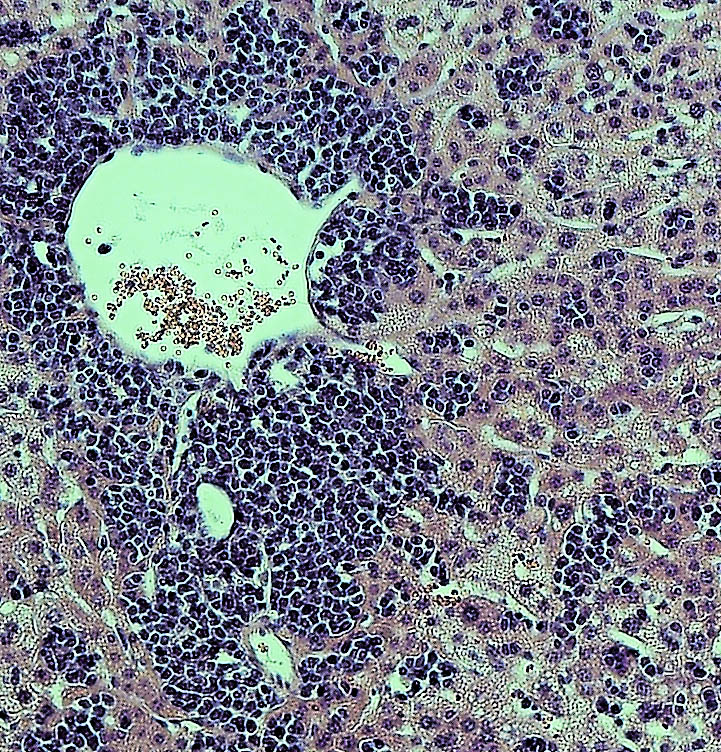

To do so, the researchers introduced additional human genes for immune system components — such as molecules that detect foreign invaders and chemical messengers called cytokines — so that the complexity of the engrafted human immune system reflected that of humans. They found that the new mice have responses to YFV-17D that are very similar to the responses seen in humans. For example, the pattern of gene expression that occurs in response to YFV-17D in the mice shared significant similarities to that of humans. This signature gene expression pattern, reflected in the “transcriptome,” or total readout of all of the genes of the organism, translated into better control of the yellow fever virus infection and to immune responses that were more specific to yellow fever.

The researchers also looked at two other types of immune responses: the cellular responses, involving production of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells that attack and kill infected cells, and the production of antibodies specific to the virus. By evaluating these three types of responses – transcriptomic, cellular, and antibody – in both mice and humans, the researchers produced a reliable platform for evaluating how well the mice can serve as proxies for humans.

Florian Douam, a postdoctoral research associate and the first author on the study, hopes that the new testing platform will help researchers explore exactly how vaccines induce immunity against pathogens, which in many cases is not well understood.

“Many vaccines have been generated empirically without profound knowledge of how they induce immunity,” Douam said. “The next generation of mouse models, such as the one we introduced in our study, offer unprecedented opportunities for investigating the fundamental mechanisms that define the protective immunity induced by live-attenuated vaccines.”

Mice bearing human cells or human tissues have the potential to aid research on treatments for many diseases that infect humans but not other animals, such as – in addition to HIV – Epstein Barr Virus, human T-cell leukemia virus, and Karposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus.

“Our study highlights the importance of human biological signatures for guiding the development of mouse models of disease,” said Ploss. “It also highlights a path toward developing better models for human immune responses.”

The study involved contributions from Florian Douam, Gabriela Hrebikova, Jenna Gaska, Benjamin Winer and Brigitte Heller in Princeton University’s Department of Molecular Biology; Robert Leach, Lance Parsons and Wei Wang in Princeton University’s Lewis Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics; Bruno Fant at the University of Pennsylvania; Carly G. K. Ziegler and Alex K. Shalek of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard Medical School; and Alexander Ploss in Princeton University’s Department of Molecular Biology.

The research was supported the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01AI079031 and R01AI107301, to A.P) and an Investigator in Pathogenesis Award by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to A.P.). Additionally, A.K.S. was supported by the Searle Scholars Program, the Beckman Young Investigator Program, the NIH (1DP2OD020839, 5U24AI118672, 1U54CA217377, 1R33CA202820, 2U19AI089992, 1R01HL134539, 2RM1HG006193, 2R01HL095791, P01AI039671), and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1139972). C.G.K.Z. was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS, T32GM007753). J.M.G. and B.Y.W. were supported by a pre-doctoral training grant from the NIGMS (T32GM007388). B.Y.W. was also a recipient of a pre-doctoral fellowship from the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research.

By Catherine Zandonella, Office of the Dean for Research

You must be logged in to post a comment.