“Time will bring to light whatever is hidden” – Horace

When this 1483 Venetian edition of the poetic works of Horace (65–8 BCE) was offered on a bookseller’s website on August 31, 2017, my eyes were drawn quickly away from its handsome Venetian typography to behold the narrow strip of vellum binding waste visible at the left side of his online image. Although neither the bookseller nor any previous owner had noticed it before, this strip was printed with the typeface used to print the Gutenberg Bible! Minutes later, Princeton had purchased the Horace, and when the book arrived, I was pleased to discover that there were actually two of these narrow vellum strips, one at the front and one at the back, folded and sewn into the binding around the first and last quires of the Horace. It was decided that Princeton’s paper conservator, Ted Stanley, should lift the old paper paste-downs inside each cover, and indeed this revealed much broader extensions of both of the vellum strips, still glued down onto the 15th-century wooden boards.

Above: Horace. Opera, with commentary by Cristoforo Landino. (Venice: Johannes de Gregoriis, de Forlivio, et Socii, 17 May 1483), as offered online in 2017.

Ted Stanley’s blog:

https://conservation.princeton.edu/2017/11/revealing-gutenbergian-text/

The results of Ted Stanley’s work are seen below, in photography by Roel Muñoz:

Front board and leaf following first quire, inverted to show the printed fragment.

Back board and leaf preceding final quire, inverted to show the printed fragment.

The two vellum fragments, now fully revealed except for two narrow widths that remains folded around the first and last six leaves of the Horace, constitute a complete leaf (folio 11 of 13) from a previously unknown 33-line edition of the Ars minor of Aelius Donatus (fl. 4th century CE), the essential Latin grammar used in medieval schools. Although it uses Johannes Gutenberg’s types, this edition most likely was printed by Gutenberg’s former colleagues in Mainz, Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer (or by Schoeffer alone).

The two vellum fragments, now fully revealed except for two narrow widths that remains folded around the first and last six leaves of the Horace, constitute a complete leaf (folio 11 of 13) from a previously unknown 33-line edition of the Ars minor of Aelius Donatus (fl. 4th century CE), the essential Latin grammar used in medieval schools. Although it uses Johannes Gutenberg’s types, this edition most likely was printed by Gutenberg’s former colleagues in Mainz, Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer (or by Schoeffer alone).

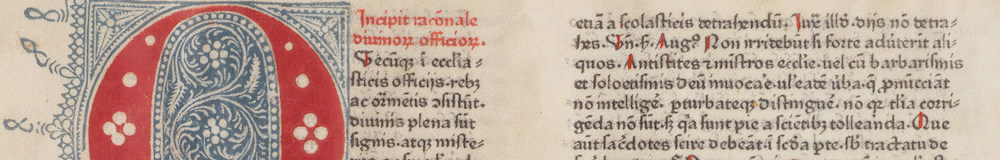

Left: Composite image of the visible portions of the Donatus leaf, still bound inside the Horace.

Whereas the red markings throughout the Donatus fragments were added by hand, the blue chapter initial A on the fragment at the back of the Horace was printed by the press in blue ink containing indigo. This feature helps to date the Donatus edition to no earlier than 1457, when Fust and Schoeffer first introduced colored initials, including the identical A, in their famous Mainz Psalter. Moreover, in line 24, the misprint ‘audiuntur’ instead of ‘audiuntor’ matches that in a nearly identical fragment at Giessen University and in a fragment of a 35-line edition in Paris, which bears the printer’s colophon of Peter Schoeffer (alone). This suggests that all three editions were printed after Johann Fust died in 1466.

Thus, a few decades after the Donatus was printed, a bookbinder saw fit to recycle the schoolbook in order to provide supports for the binding of the Horace. The rubrication of the Horace is German in style, not Italian. This strongly suggests that the book was imported to Germany from Venice at an early date. The use of a printed leaf from Mainz as binding waste likewise suggests that the Horace was bound in Germany. Moreover, an inscription by an early owner, Johann Ogier (Freiherr) Faust von Aschaffenburg (1577-1631) of Frankfurt am Main, suggests that city, with its important international book fair, as the likeliest location for the demise of the Donatus, and the binding of the Horace.

Today, no copies of any Mainz edition of the Donatus survive intact, and even such small typographic specimens as this are fabulously rare – the last time a Gutenberg-type Donatus fragment was discovered was in 1973. However, what is most important is that the present fragments were found in situ, and Princeton intends to leave them where they belong. These are the only known Mainz Donatus fragments that are still preserved within the binding that constitutes their original datable context, and it is this unique circumstance that provides important information about the lives – and deaths – of Europe’s earliest printed books.

Eric White, PhD

Acting Curator of Rare Books

Princeton University Library

You must be logged in to post a comment.