Biblia Latina (The 42-Line Bible). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, c. 1455].

Princeton University Library’s Department of Rare Books and Special Collections is pleased to announce the acquisition of the most significant specimen of the ‘Gutenberg Bible’ discovered during this century. This single leaf printed on vellum (calfskin) is a remarkable survival from what is widely considered the first book printed in Europe: the large folio Latin Bible that demonstrated the immense potential of the typographic method that Johannes Gutenberg, with financial backing from Johann Fust, developed in Mainz during the early 1450s. Given that Princeton University has been a leading center for Gutenberg-related studies ever since 1958, when the Scheide Library and its beautifully preserved two-volume paper copy of this Bible were deposited in Firestone Library (the collection was bequeathed to Princeton by William H. Scheide in 2014), the new vellum fragment provides welcome additional avenues for research into the early history of printing in the West.1

The fragment owes its survival to the fact that – more than two centuries after the Bible was printed, and long after its historical significance had been forgotten – its vellum was considered useful as recycled waste from which to make book covers. Although this grim fate once was common among obsolete books of all descriptions, this is in fact the only specimen of the Gutenberg Bible still preserved as a book binding ever to appear on the rare book market. Clearly, a discarded copy of the Gutenberg Bible was cut into hundreds of pieces for this purpose – but where, and when? The Princeton fragment itself provides evidence of unusual specificity, as it still encloses a copy of the Erneuerte und verbesserte Landes- und Procesz-Ordnung, an ordinance of litigation within the Electorate of Saxony, printed at Cöthen, Germany, in 1666. Moreover, a contemporary inscription indicates that the slender quarto volume was owned by the noted jurist Adam Cortrejus (1637–1706), who earned his doctorate at Jena in 1666, long served as Syndic in Halle, and died in Magdeburg.  This owner’s limited itinerary and the strictly local interest of the Cöthen law book both suggest that the bindery of this book – and likewise the lost Gutenberg Bible – should be localized to Saxony-Anhalt, northwest of Leipzig, during the last decades of seventeenth century.

This owner’s limited itinerary and the strictly local interest of the Cöthen law book both suggest that the bindery of this book – and likewise the lost Gutenberg Bible – should be localized to Saxony-Anhalt, northwest of Leipzig, during the last decades of seventeenth century.

This localization is especially interesting in light of Eric White’s previous research, published in 2010, concerning several dozen other vellum fragments of the Gutenberg Bible that survive as binding waste.2 Categorized by their distinct styles of rubrication (headlines, initials, and chapter numerals added by hand), these fall into eleven groups, each localized to the region in which they first were discovered, or were used as binding waste. One such group, consisting of six identically rubricated leaves, includes three leaves found in 1819 on two different bindings at the Landes- und Universitätsbibliothek in Dresden, two leaves at the Grolier Club in New York City owned by Friedrich Barnheim at Insterburg in 1867, another leaf sold by the Leipzig antiquarian Theodor Oswald Weigel by 1865 (now at the Museo Correr in Venice), as well as a leaf from Apocalypse formerly at the Universitätsbibliothek in Breslau, now lost. Dr. White localized this otherwise lost Gutenberg Bible to the vicinity of Dresden and predicted that any yet-to-be-discovered fragments exhibiting the same rubrication style very likely would hail from that same region. The fact that the rubrication exhibited by the Princeton fragment closely matches that of the Dresden group indicates that all seven fragments derive from the same lost Bible. Moreover, the three German towns associated with Princeton’s binding – Cöthen, Halle, and Magdeburg – are just to the northwest of Dresden and Leipzig.

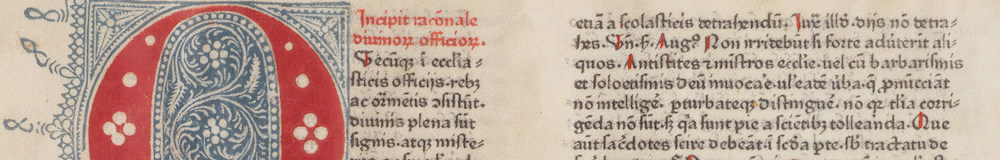

Front cover, turned sideways, showing the rubricated initial F and the chapter numeral v.

Front cover, turned sideways, showing the rubricated initial F and the chapter numeral v.

Initial F on the Princeton binding. Initial F on a fragment found in Dresden.

Initial F on the Princeton binding. Initial F on a fragment found in Dresden.

Detail of front cover, showing rubricated headline PA RA [-lipomenon], i.e., I Chronicles.

Detail of front cover, showing rubricated headline PA RA [-lipomenon], i.e., I Chronicles.

Detail of headline P found in Dresden. Detail of headline A found in Leipzig.

Detail of headline P found in Dresden. Detail of headline A found in Leipzig.

The Princeton binding was discovered by Stefan Krüger, a bookseller in Cologne, within an unexamined mixed lot of mainly 19th-century law books auctioned in Bonn c. 2006. Krüger made no announcement of his discovery until November 2016, when he advertised online that the binding would be sold on January 26, 2017, at the 31st annual Ludwigsburg Antiquaria, held near Stuttgart. In accordance with the traditions of that fair, the item would be available at a substantial (but by no means inflated) fixed price to the first applicant, or, in the event of a broader interest, to the winner of a lottery among those in attendance.

Chaos ensued on the first day of the Ludwigsburg fair, where at least 76 bidders (including Princeton’s Curator of Rare Books) drew lots for the item. The winning number belonged to a member of a consortium of German dealers headed by the independent bookseller Detlev Auvermann, an emigré to London who formerly had worked for Quaritch, Ltd. He agreed to Princeton’s immediate request for ‘first refusal’ upon determination of his sale price. While Princeton University Library administrators contemplated this major purchase, Auvermann expressed his intention to offer the item at the annual New York Book Antiquarian Book Fair beginning on March 9, 2017. The negotiations formalizing Princeton’s acquisition were completed at the end of February, and Auvermann was able to display the binding at the New York fair, marked ‘sold.’ Princeton took possession of the item on March 12.

Chaos ensued on the first day of the Ludwigsburg fair, where at least 76 bidders (including Princeton’s Curator of Rare Books) drew lots for the item. The winning number belonged to a member of a consortium of German dealers headed by the independent bookseller Detlev Auvermann, an emigré to London who formerly had worked for Quaritch, Ltd. He agreed to Princeton’s immediate request for ‘first refusal’ upon determination of his sale price. While Princeton University Library administrators contemplated this major purchase, Auvermann expressed his intention to offer the item at the annual New York Book Antiquarian Book Fair beginning on March 9, 2017. The negotiations formalizing Princeton’s acquisition were completed at the end of February, and Auvermann was able to display the binding at the New York fair, marked ‘sold.’ Princeton took possession of the item on March 12.

Although the surface of the Bible fragment is somewhat abraded and stained, as is usual for vellum leaves used as book coverings, the condition of the binding is excellent; the structure is intact, and the connections between the spine and the covers are strong. Internally, the 1666 Cöthen law book is in very good original condition. A new clam-shell box covered in navy blue Asahi backcloth was created by Princeton’s Collections Conservator, Lindsey Hobbs.

Today, 36 paper copies and 12 vellum copies of the Gutenberg Bible survive reasonably intact, either as complete Bibles or as incomplete bound volumes. Added to these are an incomplete paper copy dismantled in 1920 for sale as individual books or single leaves, and three copies on paper and eleven copies on vellum known only from binding waste. The study of the impact of early printing in Europe is well served by giving closer scholarly attention to the fourteen copies, including the one represented by Princeton’s fragment, that may not survive in the form of books, but which do survive, nevertheless.

VALUE TO RESEARCH AND INSTRUCTION AT PRINCETON

Like William Scheide himself, Princeton’s librarians, particularly the successive Scheide Librarians, have researched and published on many aspects of Gutenberg’s invention and the earliest printed books. Moreover, Princeton’s faculty have embedded book history into the university’s curriculum and are training their undergraduate and graduate students to approach the discipline with open-minded curiosity and direct experience of the original artifacts. This major acquisition is intended to continue and enrich that tradition:

- Princeton’s acquisition of the Gutenberg fragment brings a historically unique and physically ‘at risk’ survival from the first European printing enterprise into permanent institutional protection.

- Whereas all other Gutenberg Bible leaves discovered since 1900 have been removed from their host bindings, destroying historical evidence, Princeton’s purchase of this specimen establishes forever the premium value of leaving early binding waste intact.

- Contributing to an emerging field of book history research – the loss of books – this ‘miraculous’ fragmentary survival effectively encapsulates the extreme fluctuations in the Gutenberg Bible’s historical fortune over five centuries.

- To a degree unsurpassed by any similar specimen, this fragment and its host volume document the time and place at which an otherwise lost copy of the Gutenberg Bible was discarded for use as waste material for book bindings.

- The physical states of the Gutenberg Bible in Princeton’s Scheide Library and this the fragment perfectly complement each other: two paper volumes in their original binding preserved in benign neglect in Erfurt until 1840 vs. a vellum fragment from a copy cut apart by a binder c. 1666. No American library holds a similar pairing.

- Prior to this acquisition, Princeton owned the Scheide copy of the Gutenberg Bible and 19 paper leaves from 3 others (worldwide, only the Morgan Library represents as many copies). The addition of this fragment introduces a specimen printed on vellum and provides the unique opportunity to analyze the varied rubrication and provenance evidence of five copies of the Gutenberg Bible in one library.

Call #: (ExI) 2017-0006N

https://pulsearch.princeton.edu/catalog/10138910

Eric White, PhD

Curator of Rare Books

Princeton University Library

____________________

1 Paul Needham, The Invention and Early Spread of European Printing as Represented in the Scheide Library (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Library, 2007).

2 Eric Marshall White, ‘The Gutenberg Bibles that Survive as Binder’s Waste’, in Early Printed Books as Material Objects. Proceedings of the Conference Organized by the IFLA Rare Books and Manuscripts Section. Munich, 19-21 August 2009. Bettina Wagner and Marcia Reed, eds. (Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, 2010), 21-35.

The two vellum fragments, now fully revealed except for two narrow widths that remains folded around the first and last six leaves of the Horace, constitute a complete leaf (folio 11 of 13) from a previously unknown 33-line edition of the Ars minor of Aelius Donatus (fl. 4th century CE), the essential Latin grammar used in medieval schools. Although it uses Johannes Gutenberg’s types, this edition most likely was printed by Gutenberg’s former colleagues in Mainz, Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer (or by Schoeffer alone).

The two vellum fragments, now fully revealed except for two narrow widths that remains folded around the first and last six leaves of the Horace, constitute a complete leaf (folio 11 of 13) from a previously unknown 33-line edition of the Ars minor of Aelius Donatus (fl. 4th century CE), the essential Latin grammar used in medieval schools. Although it uses Johannes Gutenberg’s types, this edition most likely was printed by Gutenberg’s former colleagues in Mainz, Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer (or by Schoeffer alone).

This owner’s limited itinerary and the strictly local interest of the Cöthen law book both suggest that the bindery of this book – and likewise the lost Gutenberg Bible – should be localized to Saxony-Anhalt, northwest of Leipzig, during the last decades of seventeenth century.

This owner’s limited itinerary and the strictly local interest of the Cöthen law book both suggest that the bindery of this book – and likewise the lost Gutenberg Bible – should be localized to Saxony-Anhalt, northwest of Leipzig, during the last decades of seventeenth century.

You must be logged in to post a comment.