A Princeton University-led study has revealed an emergent electronic behavior on the surface of bismuth crystals that could lead to insights on the growing area of technology known as “valleytronics.”

The term refers to energy valleys that form in crystals and that can trap single electrons. These valleys potentially could be used to store information, greatly enhancing what is capable with modern electronic devices.

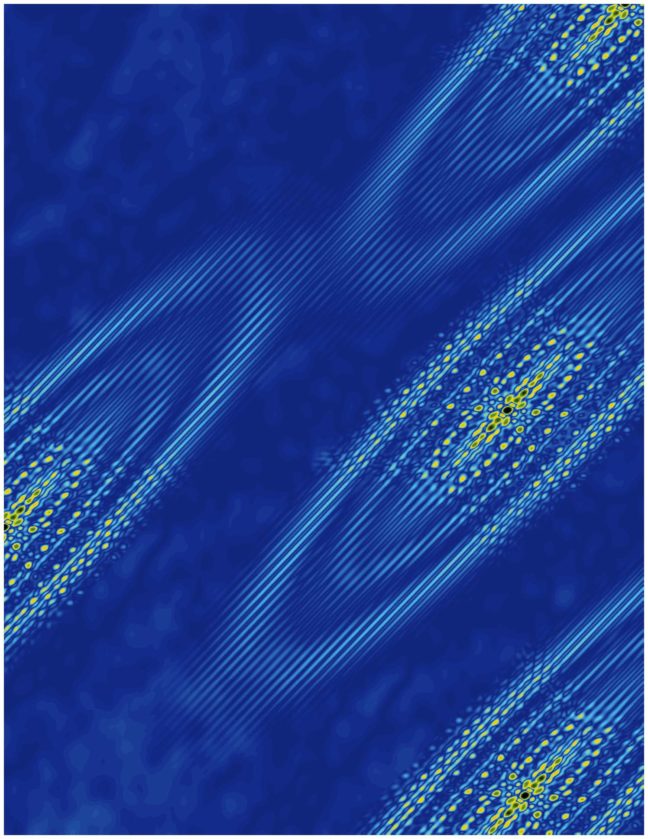

In the new study, researchers observed that electrons in bismuth prefer to crowd into one valley rather than distributing equally into the six available valleys. This behavior creates a type of electricity called ferroelectricity, which involves the separation of positive and negative charges onto opposite sides of a material. The study was published in the journal Nature Physics.

The finding confirms a recent prediction that ferroelectricity arises naturally on the surface of bismuth when electrons collect in a single valley. These valleys are not literal pits in the crystal but rather are like pockets of low energy where electrons prefer to rest.

The researchers detected the electrons congregating in the valley using a technique called scanning tunneling microscopy, which involves moving an extremely fine needle back and forth across the surface of the crystal. They did this at temperatures hovering close to absolute zero and under a very strong magnetic field, up to 300,000 times greater than Earth’s magnetic field.

The behavior of these electrons is one that could be exploited in future technologies. Crystals consist of highly ordered, repeating units of atoms, and with this order comes precise electronic behaviors. Silicon’s electronic behaviors have driven modern advances in technology, but to extend our capabilities, researchers are exploring new materials. Valleytronics attempts to manipulate electrons to occupy certain energy pockets over others.

The existence of six valleys in bismuth raises the possibility of distributing information in six different states, where the presence or absence of an electron can be used to represent information. The finding that electrons prefer to cluster in a single valley is an example of “emergent behavior” in that the electrons act together to allow new behaviors to emerge that wouldn’t otherwise occur, according to Mallika Randeria, the first author on the study and a graduate student at Princeton working in the laboratory of Ali Yazdani, the Class of 1909 Professor of Physics.

“The idea that you can have behavior that emerges because of interactions between electrons is something that is very fundamental in physics,” Randeria said. Other examples of interaction-driven emergent behavior include superconductivity and magnetism.

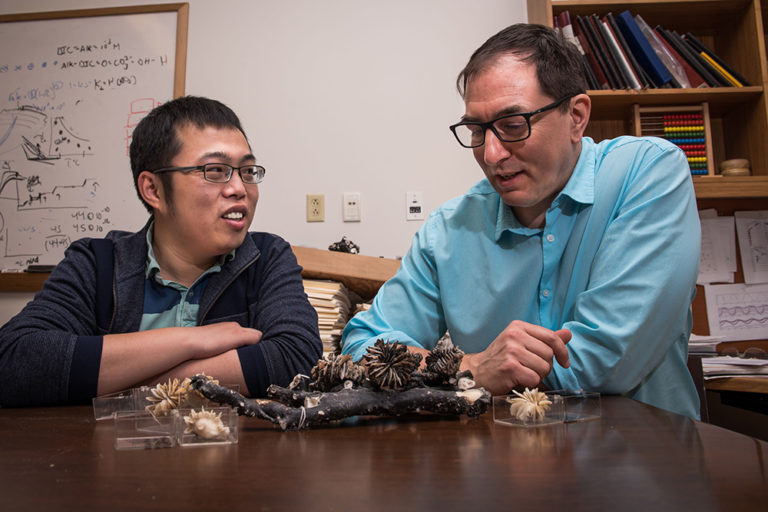

In addition to Randeria, the study included equal contributions from Benjamin Feldman, a former postdoctoral fellow at Princeton who is now an assistant professor of physics at Stanford University, and Fengcheng Wu, a postdoctoral researcher at Argonne National Laboratory. Additional contributors at Princeton were Hao Ding, a postdoctoral research associate in physics, and András Gyenis, a postdoctoral research associate in electrical engineering; Ji Huiwen, who earned a doctoral degree at Princeton and is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California-Berkeley; Robert Cava, Princeton’s Russell Wellman Moore Professor of Chemistry; and Yazdani. Additional contributions came from Allan MacDonald, professor of physics at the University of Texas-Austin.

The study was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation as part of the EPiQS initiative (GBMF4530), the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE-BES grant DE-FG02-07ER46419), the U.S. Army Research Office MURI program (W911NF-12-1-046), the National Science Foundation’s MRSEC program through the Princeton Center for Complex Materials (NSF-DMR-142054 and NSF-DMR-1608848), and the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Transformative Technology Fund at Princeton. Work at University of Texas-Austin was supported by DOE grant (DE-FG03-02ER45958) and by the Welch Foundation (TBF1473).

The study “Ferroelectric quantum Hall phase revealed by visualizing Landau level wave function interference,” by Mallika T. Randeria, Benjamin E. Feldman, Fengcheng Wu, Hao Ding, András Gyenis, Huiwen Ji, R. J. Cava, Allan H. MacDonald, and Ali Yazdani, was published online May 14, 2018, and in print in August, 2018, in the journal Nature Physics.

By Catherine Zandonella

You must be logged in to post a comment.