Section III: The De-materialized Object: An Analysis of Man Ray’s Objects

Destroying Objects

In the 1930’s, Surrealist artists experimented with many ways of arranging the objects in an attempt to subvert their traditional meanings and use-values. As we have discussed in earlier sections, the traditional meaning, or association, of the object was often replaced with an alternative one relating to the subconscious to create an unexpected visual effect that could rouse the senses and inspire revolution of thought. However, one Surrealist, Man Ray, had a much more ambitious goal than a simple replacement: de-materializing the object completely by exploring a new format of photography called Rayographs.

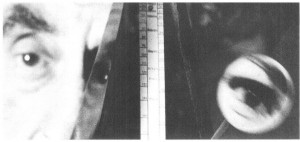

Man Ray’s interest in establishing a method of de-materializing the object likely originated in 1923 when he became fixated on the problem of how an artist is always forced to make objects to be visually consumed. His 1923 work, Object to be Destroyed (pictured left), reflects his inner need for a companion through the tormenting process. Consisting of a metronome with the photograph of an eye attached to the oscillating needle, Object to be Destroyed constitutes an automaton that watches the viewer as they go about their daily routine, emphasized by the repetitive beat of the functioning metronome. According to Man Ray, the object was created because “a painter needs an audience, so I also clipped the photo of an eye to the metronome’s swinging arm to create the illusion of being watched as I painted.” In other words, the automaton represents a silent witness accompanying Man Ray inside the studio while he is making objects for visual consumption.

Man Ray’s interest in establishing a method of de-materializing the object likely originated in 1923 when he became fixated on the problem of how an artist is always forced to make objects to be visually consumed. His 1923 work, Object to be Destroyed (pictured left), reflects his inner need for a companion through the tormenting process. Consisting of a metronome with the photograph of an eye attached to the oscillating needle, Object to be Destroyed constitutes an automaton that watches the viewer as they go about their daily routine, emphasized by the repetitive beat of the functioning metronome. According to Man Ray, the object was created because “a painter needs an audience, so I also clipped the photo of an eye to the metronome’s swinging arm to create the illusion of being watched as I painted.” In other words, the automaton represents a silent witness accompanying Man Ray inside the studio while he is making objects for visual consumption.

However, by 1932, Man Ray’s attitude toward the work had become much more aggressive, with the instrument no longer representing a witness, but an antagonist extracting the knowledge of the artist at work. In replacing the picture of an unidentified eye with one of his ex-lover Lee Miller, Man Ray reveals Miller to be the antagonist. (Howarth, Tate).

This is supported by Man Ray’s publishing the following instructions beside an ink drawing of the Object to Be Destroyed in the 1932 avant-garde journal This Quarter:

Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.

Here, keep going to the limit of endurance refers to the pressure within the everyday life to produce and perform at the rate of an automaton until the very end where exhaustion leads to violence and the final destruction of the process. We can see Man Ray is establishing the content of and inspiration for Object to Be Destroyed to be not simply a lover’s quarrel, but the notion that the future creative process of object-making is at stake since the artist is really no longer truly alone inside the studio. Like the object intended for visual consumption, the process of object making for the artist has also become also subjected to constant surveillance. The creative process has become just as valuable as the final product. The metronome automaton, which began as an accompaniment to the artist, has become a machine for surveillance and extraction of value from the artist while he performs and manufactures.

Self Portrait with Automaton

The more that Man Ray wanted to destroy the automaton, the more fascinated he became with it. In his 1964 self-portrait (untitled, pictured right), Man Ray’s face is placed behind the automaton. Through this juxtaposition, Man Ray presents himself as half human-half automaton. His real face is sliced in half with the automaton on one side with a new eye that can oscillate constantly back and forth.

The more that Man Ray wanted to destroy the automaton, the more fascinated he became with it. In his 1964 self-portrait (untitled, pictured right), Man Ray’s face is placed behind the automaton. Through this juxtaposition, Man Ray presents himself as half human-half automaton. His real face is sliced in half with the automaton on one side with a new eye that can oscillate constantly back and forth.

Furthermore, his obsession with the automaton version of the eye with the capability to record information through repetition seems to push him towards studying the camera and photography. When asked about Man Ray’s consideration of the eye, literary critic Pierre Bourgeade suggested it to be the motivating factor behind Man Ray’s use of the camera:

But the human eye is the most perfect and the smallest instrument in the world: it works in tandem with the brain, that inverts the image, already inverted in the human eye like in a camera; the brain rectifies and enlarges it to its natural dimensions at the same time.

Realizing the immense potential of the eye, Man Ray attempts to utilize the contraption that best mirrors its properties: the camera. As suggested in his self-portrait’s combining a real and mechanical eye, Man Ray believed that by employing his natural vision in conjunction with mechanical vision, an enhanced, more representative perspective could be realized.

Photo Painting

Working constantly between painting and photographs in the beginning of his career, Man Ray seemed to be searching for a new technique that could mix both kind of eyes to create a new method replace painting.

It was in a 1929 interview with Jean Vidal on the occasion of a solo exhibition at the Galerie des Quatre Chemins, where Man Ray was showing recent oil paintings as well as the striking photograms he called “Rayographs.” “Painting is dead, finished,” he added, by way of explanation (Laxton 25).

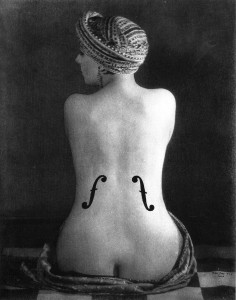

Within photogr aphy, Man Ray used techniques of juxtaposition and image cropping to increase the distance between the original object and the viewer, providing a new perspective of the object. Le Violon d’Ingres 1924 (pictured left) does this well with the violin F holes or notes overlaid onto the women’s back within the photograph to create a double reading. The instrument is interpreted as the female contour whilst the body is suggested to be played as an instrument.

aphy, Man Ray used techniques of juxtaposition and image cropping to increase the distance between the original object and the viewer, providing a new perspective of the object. Le Violon d’Ingres 1924 (pictured left) does this well with the violin F holes or notes overlaid onto the women’s back within the photograph to create a double reading. The instrument is interpreted as the female contour whilst the body is suggested to be played as an instrument.

In L e Baiser 1935 (pictured right), the two faces are put next to each other to suggest the mirroring has created an alter ego. Although the two faces look alike, their expressions are completely differently, with one in an intimate gaze and the other looks intensely beyond creating two personalities within one frame. These general techniques within painting and photography would continue to be used later on when Man Ray invents the Rayographs.

e Baiser 1935 (pictured right), the two faces are put next to each other to suggest the mirroring has created an alter ego. Although the two faces look alike, their expressions are completely differently, with one in an intimate gaze and the other looks intensely beyond creating two personalities within one frame. These general techniques within painting and photography would continue to be used later on when Man Ray invents the Rayographs.

The more Man Ray pushed the limits of photography and painting, the more he tried to find different ways to mix similarities between how paintings and photographs are produced. In fact, when describing his work in the book self-portrait 1963, Man Ray claimed the he was “trying to do with photography what painters were doing, but with light and chemicals, instead of pigment, and without the optical help of the camera” (as quoted in Laxton 26).

Animated Process

When Man Ray made the Rayographs, one could read the object tracing process, the technique of impressing the object to the photographic paper to create movement similar to cinema. According to Laxton, the Rayograph functions as follows:

First, as contact prints produced by placing objects directly onto treated paper, they are unique images made without the technological mediation of the camera lens. Thus they excuse themselves from the critical discourse that grasps photography as a mechanical means of reproduction. (Laxton)

The reason for Man Ra y’s search for an animated effect also had to do with his interest in expressing a story within his photographs. One of Man Ray’s earliest Rayograghs, The Kiss (1922, pictured left) clearly portrays the narrative effect of the body kissing and performing in space using different intensities of silhouettes overlaid on top of each other. The bodies and hands in the photograph seem to merge in one continuous motion creating a bodily cinematic effect.

y’s search for an animated effect also had to do with his interest in expressing a story within his photographs. One of Man Ray’s earliest Rayograghs, The Kiss (1922, pictured left) clearly portrays the narrative effect of the body kissing and performing in space using different intensities of silhouettes overlaid on top of each other. The bodies and hands in the photograph seem to merge in one continuous motion creating a bodily cinematic effect.

However, Man Ray’s interest to animate the body in the photograph would later shift as he began to experiment with inanimate objects. However, Man Ray retained his previous methods of Rayography and employed them in his work with inanimate objects:

“I threw pins and thumbtacks at random; then turned on the white light for a second or two, as I had done for my still Rayographs.”

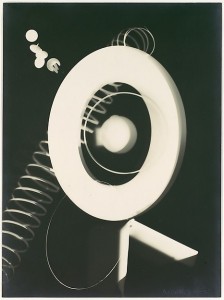

Here, Man Ra y describes his efforts at process art, or the ability to capture motion all within one photograph. One can see this in the 1922 work of Rayograph (pictured right). The animated view of the objects is performed, creating a space of the object that has never been seen through the contact between the print and the object. Instead of the physical word represented, another type of world is brought to life in the prints. The images display a pictorial field radically distorting what the natural visible world would look like, pushing the limits of physical reality to the extreme, away from what one would see in a production of photograph by the camera. The motion distortion is created when objects are moved between different distances to make the contact image.

y describes his efforts at process art, or the ability to capture motion all within one photograph. One can see this in the 1922 work of Rayograph (pictured right). The animated view of the objects is performed, creating a space of the object that has never been seen through the contact between the print and the object. Instead of the physical word represented, another type of world is brought to life in the prints. The images display a pictorial field radically distorting what the natural visible world would look like, pushing the limits of physical reality to the extreme, away from what one would see in a production of photograph by the camera. The motion distortion is created when objects are moved between different distances to make the contact image.

The new reality could be seen as a trace of the original revealing not the presence but the absence of the world as explained by Malt on contact images.

“They require an act of contact in order for the trace or image to come into existence, but it is a contact that much also necessarily end in order for that trace or image to be seen. Made from presence and from loss, they have a unique relation to time, recording an action, a moment of being, but doing so by virtue of that presence now having become an absence.” (Malt 101)

In producing this absence, Man Ray has found a way for objects to exist in their absence, an re-animation of the object within the photograph.

De-materializing

The Rayograph creates an out of focus effect, by adjusting the distance between the object and the paper to give off varying degrees of transparency. The object can be read as oscillating between what the object is and the disappearance of the object as suggested by Malt on contact images.

“My contention is that contact images themselves set up a kind of oscillation between being ‘objects’ and being ‘things’, between signification and being, or between what Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht has called ‘meaning effects’ and ‘presence effects’.” (Malt 92)

The p lay with oscillation allows the objects to de-materialize through this process. The Comb, Straight Razor, Blade, Needle and Other Forms 1922 (pictured left) shows very well this disappearance effect by layering the objects at different distances from the photograph. Dimensions of the object are also played with here, using very thin objects and thick objects to create different intensities of de-materialization with the background.

lay with oscillation allows the objects to de-materialize through this process. The Comb, Straight Razor, Blade, Needle and Other Forms 1922 (pictured left) shows very well this disappearance effect by layering the objects at different distances from the photograph. Dimensions of the object are also played with here, using very thin objects and thick objects to create different intensities of de-materialization with the background.

But more importantly, the oscillating effect within the Rayograph gives the objects a new-found ability to shift between different forms of abstraction, quality, perception, and materiality creating the de-materialized object. One can say that Man Ray has finally achieved his initial interest to destroy the object by finding a new way to produce the object without the automatic camera effect and by using the photo painting to replace traditional painting as the next advancement of object making.