By the Department of Molecular Biology

A new study indicates an essential role for a maternally inherited gene in embryonic development. The study found that zebrafish that failed to inherit specific genetic instructions from mom developed fatal defects earlier in development, even if the fish could make their own version of the gene. The study by researchers at Princeton University was published Nov. 15 in the journal eLife.

When female animals form egg cells inside their ovaries, they deposit messenger RNAs (mRNAs) – a sort of genetic instruction set – in the egg cell cytoplasm. After fertilization, these maternally supplied mRNAs can be translated into proteins required for the early stages of embryonic development, before the embryo is able to produce mRNAs and proteins of its own.

More than thirty years ago, researchers discovered that mRNAs encoding a protein called Vg1 are deposited in the cytoplasm of frog eggs. “vg1 is famous for being one of the first recognized maternal mRNAs,” said Rebecca Burdine, associate professor of molecular biology at Princeton. “Many papers have been written on how this RNA is localized and regulated, but it was never clear what the Vg1 protein actually does in the developing embryo.”

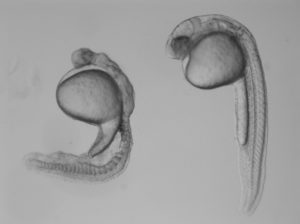

In the study, Burdine and two graduate students Jose Pelliccia and Granton Jindal used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to remove Vg1, known as Gdf3 in zebrafish. Embryos that couldn’t produce any Gdf3 of their own–but received a healthy portion of the gdf3 mRNA from their mothers–developed perfectly normally. But embryos that didn’t receive maternal gdf3 mRNA showed major defects early on in their development, dying just three days after fertilization.

“If gdf3 is not supplied to the egg by the mother, the fertilized egg cannot produce two of the three major types of cells required for development,” Burdine said. “The embryos lack all [cell types known as] mesoderm and endoderm and are left with skin and some neural tissue, [which derive from the third major cell type, the ectoderm].”

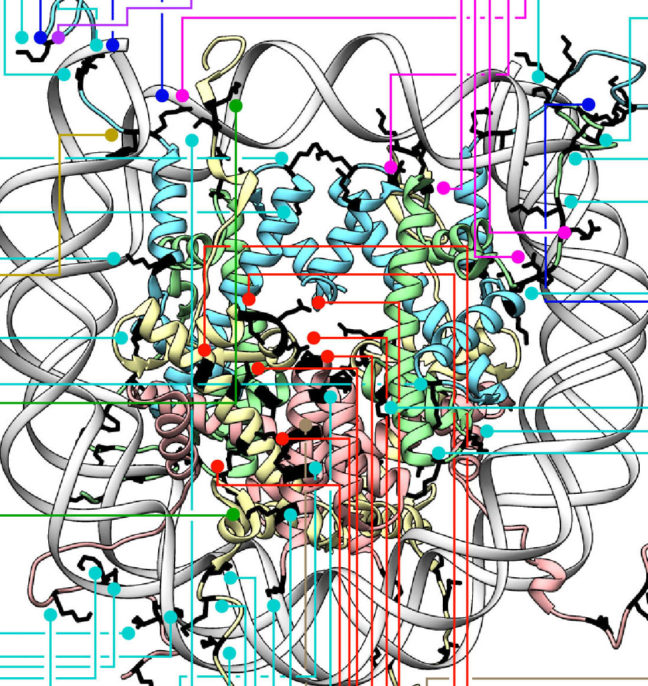

Vg1/Gdf3 is a member of the TGF-beta family of cell-signaling molecules. Two other members of this family, Ndr1 and Ndr2, are required to form the mesoderm and endoderm early in zebrafish development. Embryos lacking maternally supplied gdf3 look very similar to embryos lacking both of these proteins, which are analogous to the Nodal 1 and 2 proteins in mammals.

The researchers found that maternal gdf3 is required for Ndr1 and Ndr2 to signal at the levels necessary to properly induce the formation of mesoderm and endoderm cells in early zebrafish embryos. In the absence of gdf3, Ndr1 and Ndr2 signaling is dramatically reduced and embryonic development goes awry.

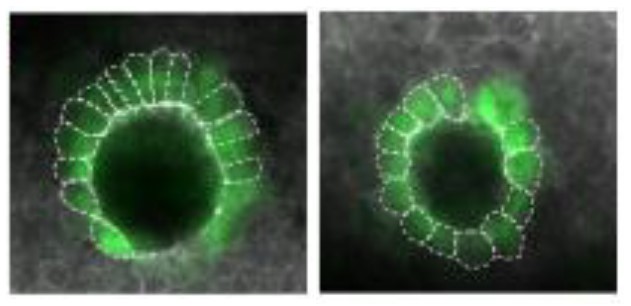

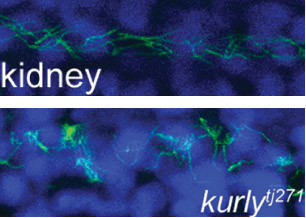

Nodal signaling is also required later in zebrafish development when it helps to establish differences between the left and right sides of the developing embryo. It does this, in part, by directing the formation of an organ known as Kupffer’s vesicle, whose asymmetric shape helps determine the embryo’s left and right sides. Subsequently, Nodal signaling induces the expression of a third Nodal protein, called southpaw, in a group of mesoderm cells on the left-hand side of the embryo.

To investigate whether maternally supplied gdf3 mRNA also plays a role in left-right patterning, the researchers used a series of experimental tricks to supply embryos with enough Gdf3 protein to form the mesoderm and endoderm and survive until the later stages of embryonic development.

As predicted, these embryos showed defects in left-right patterning. Their Kupffer’s vesicles were abnormally symmetric in shape, and southpaw expression was greatly reduced, suggesting that gdf3 is also required for optimal Nodal signaling during later stages of embryonic development. At this stage, however, embryonic gdf3 seems to be capable of doing the job if maternally supplied gdf3 is absent.

Nodal and Vg1 proteins are known to bind to each other in other species. “Thus, we hypothesize that Gdf3 combines with Ndr1 and Ndr2 to facilitate Nodal signaling during zebrafish development, acting as an essential factor in embryonic patterning,” said Pelliccia, a graduate student in molecular biology. Co-author Jindal earned his Ph.D. in chemical and biological engineering in 2017.

At the same time as Burdine and colleagues, two other research groups, led by Joe Yost at the University of Utah and Alex Schier at Harvard University, made similar findings on the role of gdf3 during zebrafish development. “All three groups worked together to co-submit and co-publish in eLife, allowing the students involved to all get credit for their hard work,” Burdine said. “It’s a great example of how science should be done.”

###

The research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R01HD048584) and the National Science Foundation (graduate research fellowship DGE 1148900).

Citation: Pelliccia, J.L., G.A. Jindal, and R.D. Burdine. Gdf3 is required for robust Nodal signaling during germ layer formation and left-right patterning. eLife. 6: e28635 (2017). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.28635

You must be logged in to post a comment.