Last week I talked about the history of the battle between the two web giants, Facebook and Google, and how Google plans to win with its “one Google experience.” If you haven’t read part 1 of this post, I strongly suggest reading it first as there will be references back to certain arguments I brought up. As for the rest, here is part 2, detailing Facebook’s similar yet fundamentally different strategy and how this conflict will affect us users in the end.

Facebook Everywhere

Try to sign up for an account on a website today, and most of the times you will see a little blue tab labeled “Connect with Facebook.” When did Facebook become so ubiquitous? Facebook originally started as a just an online social network, but ever since then, it has evolved to become so much more. Indeed, Facebook has slowly crawled its way outside of facebook.com and into more of our lives. Its goal, ultimately, is to be present everywhere, or as Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, put it, to be “a social layer across every device.”

It is really easy to generalize Facebook’s strategy to be the same as Google’s; however, to do so would be a grave mistake. While the two web giants definitely have similar, if not the same end goal, how they approach the goal is completely different. As detailed in part 1, Google wants to be in every part of your life, and in order to do that, it has built an ecosystem such that you never have to leave Google’s site. Facebook, on the other hand, sees things differently. While it would certainly love you to stay on its site, Facebook also recognizes that it cannot satisfy your every need.

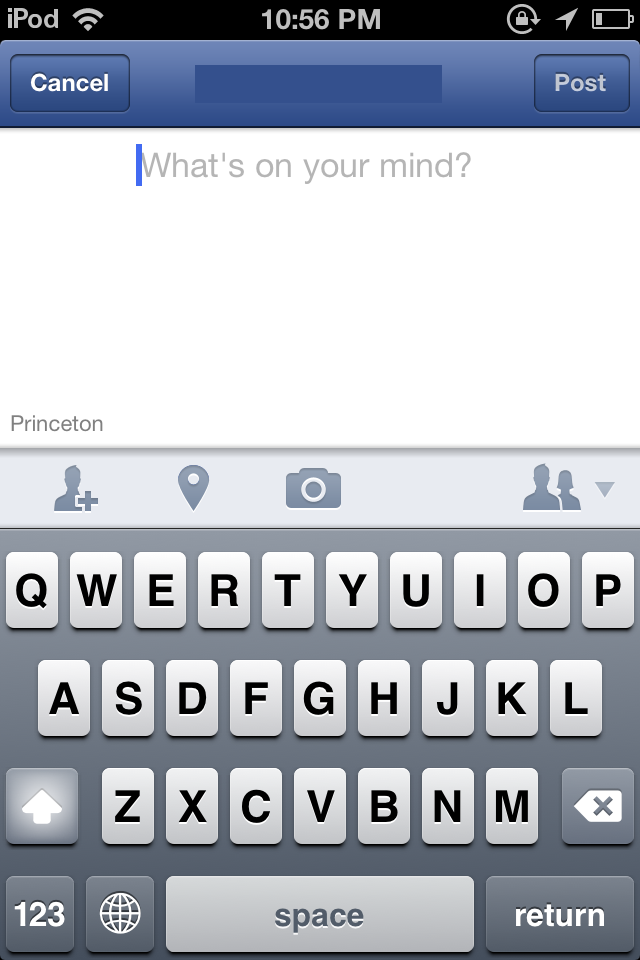

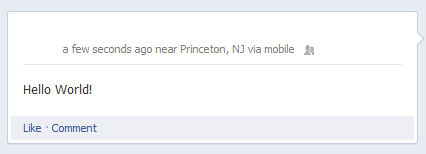

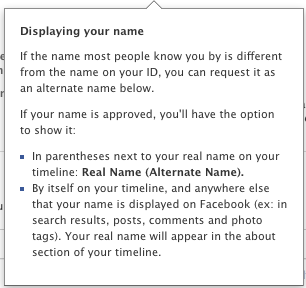

Instead of keeping everyone on its website, Facebook aims to be everywhere. One way it has been doing that is through partnerships. In the past few years, Facebook has created partnerships with several strategic partners to fill out the void left by its services. For example, instead of building a music store, Facebook partners with Spotify. Instead of building a video chat system, Facebook turns to Skype. Instead of building its own app store, Facebook creates an online catalog of all Facebook-connected apps that links back to other app stores. Very recently, Facebook struck a deal with Dropbox to bring better file-sharing to the social network. Facebook also has been working hard with Apple, Microsoft, and, ironically, Google to build system-level Facebook integration directly into their mobile operating systems. (To be honest, due to the openness of Android, Google may not have a say in the matter.) Facebook also has worked hard to create a powerful software development kit (SDK), allowing anyone to build Facebook-connected app, whether mobile or on the web, and send user data back to Facebook. Yahoo is a prime example here with its social reader, which allows Facebook to know exactly which article the user read. The famous/infamous blue “Connect with Facebook” tab is another example, which saves the user the hassle of creating a new account in return for giving Facebook information about the users’ activities on those sites. Through these strategic partnerships and a strong developers’ SDK, Facebook hope that wherever you are, Facebook will be there, too.

Personally, Facebook’s strategy is a lot more feasible than Google’s. In fact, Google’s strategy has put Google itself into a catch-22 situation; by choosing to compete with everyone, Google risks losing a portion of data just because its users choose to go to someone else for a certain service. For example, Facebook’s partnerships allow its social network to be integrated into Windows Phone, iOS, and Android. Google, sadly, gets to integrate Google+ into only one of the three. It is for this very reason that Facebook is not building a phone; it can simply achieve better results through partnerships.

Facebook needs to find a way to make itself present everywhere, not just social network. In many areas, creating partnerships will suffice. However, there are a few key areas that Facebook can simply provide a better solution. One such area is search engine. If anyone can break Google’s search monopoly, it is Facebook. Facebook may already have a deal with Microsoft and its Bing search engine, but, honestly, Bing is not making a dent. Google may have access to virtually all the search history in the world, but Facebook has access to the intimate parts of its users’ lives. Because of this, Facebook should (and it actually is) build its own search engine.

Effect on Users

So, what does this battle means for us users? Superficially, we seem to gain from the battle. After all, this is competition, and competition is good for consumers, right? Not exactly…as a consequence of this battle, unless you choose to restrict your web activities to just one of the companies, there is no easy way to integrate your web experience. For instance, Google’s introduction of Search Plus Your World seemed benevolent at first. However, Facebook and Twitter later accused Google of prioritizing social results from its own Google+ over other social networks’. This eventually led to a few companies, including Facebook and Twitter, creating a tool to “neutralize” Google’s tactic. This tool, named after Google’s very own slogan when it first started as a search engine, is called “Don’t Be Evil.” The deadliest sin is when I google myself, my Facebook profile is not the first result, or even the first page.

Now, imagine an ideal world where these two companies collaborate instead of battle. Facebook would be the ultimate social network, and Google would be the ultimate search engine. Whenever you search on the Facebook search bar, Google search results are integrated in. Similarly, when you search on Google, Google incorporate Facebook data into search results, so you will see exactly which articles your friends “liked.” This is only an elementary idea of how Facebook and Google could collaborate and give us users the best experience on the web. Unfortunately, these two giants are more focused on owning our web browsing screen rather than enriching it.