Computer viruses isn’t news. When you first learned to use a computer (at least if you are from a younger generation), the first thing you are told to do is probably to run anti-virus softwares. Sadly, these softwares are most probably the most annoying part about computers. Then came the iPhone, the miniaturized computer that somehow has escaped infections despite its popularity (the same, however, can’t be said about its rival, Android). What is the difference between iPhone and all the other operating systems? Can any of the lessons be applied to protect our personal computers? (Hint: the answer is yes.)

To understand why the iPhone has escaped software attacks, one must understand fundamentally how its operating system, iOS, handles apps. iOS, unlike other operating systems, does not allow apps the full access to the system, and it does so by a technique called Sandboxing. The best way to understand Sandboxing is to picture a physical sandbox. Each application on iOS gets its own little Sandbox to play with, and it is not allowed to go into anyone else’s sandbox. This means that the apps each get their own documents folder. This is why the iPhone lacks a file system. They are also not allowed to do anything outside of their own sandboxes at all. This is the key to how iOS escapes malware. It is impossible for any iOS apps to, for example, disable the home button to keep you in the app or to delete your documents in another app. How then do these apps get access to system features, like the calendar and camera? In a least techie way of describing this, Apple built doorways known as “API” for each of these specific functions. If the Facebook app wants to access your photos, for example, it needs to open the photo doorway. Android has a similar, but much weaker, Sandboxing system, which is why Android phones can be customized as one pleases.

Sandboxing is just half of the story. The other half is the App Store. It is well known that the App Store is this amazing collections of apps, but many may not know that Apple actually has to screen each app before they are put on the store. This way, most of the spotty apps are removed, and the few exceptions are quickly removed once discovered. All the apps in the App Store must also follow certain rules, Sandboxing being one of them. As Apple proudly heralded in its World Wide Developer Conference 2010, the App Store is a “a curated platform (and) it is the most vibrant app platform on the planet.” The keyword here is “curated.” Every app on the App Store must be given the “ok” from Apple, and this is why iOS users do not have to worry about security threats from these apps.

As you may have already noticed, in return for security, the users must give up control, at least on iOS. Obviously, this does not work for personal computers. We want our computers to be as customizable as possible so that we may do whatever we want with it. This struggle between control and customizability is mind-boggling, and it looked like we may have to stick with anti-virus softwares. However, just a few months ago, Apple released a new version of Mac OS X with a new security system, and the only word that can do it justice, and barely so, is “brilliance.”

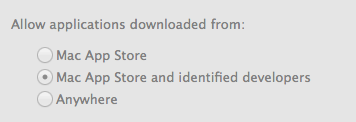

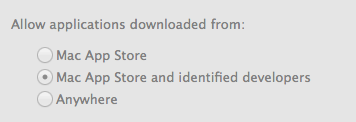

Here is how the current Mac security system works. With the release of the latest version of Mac OS X, Apple has implemented a new feature called “Gatekeeper.” Gatekeeper is, as the name may imply, is all about preventing malicious software from entering into the computer. Basically, all Macs categorize applications into three main camps. The first camp houses all the apps downloaded from the Mac App Store (MAS). These apps receive the same benefits as those downloaded from the iOS App Store, mentioned earlier. The second camp is basically comprised of all apps not fitting into the previous camp or the next one. The last camp, however, is where the brilliance of Gatekeeper is.

The third camp is called “Apps from Identified Developers.” Many people will download apps exclusively from MAS and that will be enough. However, many will also discover that many of their favorite apps are not on the store. These apps include Google Chrome, VLC Media Player, and Microsoft Office. There are a number of reasons why these apps are not on MAS. Some, like Chrome, simply breaks the rules of MAS by its very nature, in this case running a third-party web browser engine. Many apps are also not capable of living in the Sandbox without compromising their feature sets. Others simply do not want to go through Apple for distribution of their softwares. After all, Apple charges 30% of all sales and takes a longer than optimal period of time to approve applications. These limitations effectively debunk MAS as a plausible exclusive channel to download applications. Apple needs to come up with something better, and along comes the Developer ID system. The way the system works is that any registered member of the Mac Developer Program ($99/year, like iOS) can request a Developer ID from Apple and sign it into their apps. If a developer is discovered to be malicious, Apple can easily revoke the certificate. In short? Apple now curates developers instead of individual apps. This way, Apple can provide roughly the same (maybe slightly less) safe environment that users have come to expect from its stores without actually imposing the rules and limitations of the stores.

Now that you understand how Macs identify applications, it is not hard to understand how Gatekeeper works. It is as easy, literally, as a choice between three settings: MAS apps only, MAS apps + apps from identified developers, and all apps. Defaulted at the second setting, Gatekeeper determines which apps can be run and which one should not be run. This way, Mac users do not have to worry about malicious applications. Best of all, Gatekeeper’s deterrence can easily be overcome by right clicking and choosing “Open.” Suppose Google is not a registered developer, but you know that Google Chrome is not a malicious software. Gatekeeper makes it really easy for you to override its judgement, and it remembers your settings so it does not ask you a second time. It does not take a genius to see the brilliance of this implementation. Gatekeeper protects the average users without them having to do anything while at the same time giving power users the control and customizability they crave.

Many people bemoan the resemblance of Gatekeeper to Windows’ infamous “Allow Access/Run As Administrator” implementation, but little usage and an open mind will quickly rectify the mistaken belief. Windows’ implementation blocks administrative rights to all apps, safe or not. Gatekeeper, on the other hand, goes the extra mile of first determining whether the app is from a trusted source. Only when it suspects an app does it prevent the app from running. This is a subtle but game-changing difference.

Is Gatekeeper the perfect implementation of a security system? Nope. It is, however, the best one so far. Apple intended the current version of the Mac to bring the best of iOS and re-imagine it for the personal computer, and they have certainly done that in the security aspect. Malicious developers will always try to find a way to get around Gatekeeper and other firewalls, but at least for now, Mac users can rest easy knowing that they are safe.