Harvard reminded the world last week why free speech is an ever-present issue on college campuses. When students woke up to satirical flyers slipped under their doors, inviting them to join the school’s latest final club, “the Pigeon,” administrators were not amused. For the poster’s tongue-in-cheek header, “Inclusion* Diversity** Love***,” was complemented by the footnote, “*Jews need not apply / **Seriously, no f—ing Jews. Coloreds OK. / *** Rophynol (sic)” — the final comment referring to the date rape drug, rohypnol. Oft-criticized as bastions of exclusivity and sexism, Harvard’s all-male final clubs are perhaps deserving of the spirit of the flyer. And though its rhetoric pushed the limits of acceptable speech (or did it? consider the extent of satire used by The Onion), the writer’s (or writers’) goal of bringing attention to ills within the campus community was surely realized.

This is not the first time Harvard’s administration has shown a distaste for free speech. Last year, incoming freshmen were encouraged to sign an oath binding them to act with “civility,” “inclusiveness,” and “kindness” on campus. The oath received much criticism. Is compulsory kindness and forced civility really what a college campus needs? In many cases, kindness is antithetical to calls for change, civility is incompatible with the actions needed to enact reform, and inclusiveness can create artificial and confusing rules.

Now imagine if the flyer was not physically printed, but distributed via a social network — probably Facebook. Would the administration have reacted differently? Would it have jurisdiction over content posted on the network? Consider that anonymity on Facebook is near-impossible, so the social barriers to cheeky language like what was used in the poster would have been higher. In other words, the writer would probably have abstained from using racial slurs. Would the flyer still have ticked off the administration? Though printed media slipped under one’s door overnight naturally garners attention, a shocking viral post distributed through Facebook can no doubt have the same power, and is easier for the author to disseminate.

The real problem here is that colleges are increasingly unwilling to allow unpopular ideas to be debated in the public sphere at the expense of civility, inclusiveness, and kindness. In my opinion, this hyper-sensitivity is counterproductive and ultimately reduces students’ ability and impetus to debate social ills and present unpopular ideas. This is where the First Amendment comes in — or doesn’t. While public universities, funded by taxpayers, cannot restrict free speech in the same way that one cannot restrict free speech at a town center, private universities (like Harvard) don’t have to follow the principles of the Constitution. Harvard has every legal right to make rules limiting speech in order to further its particular educational goals.

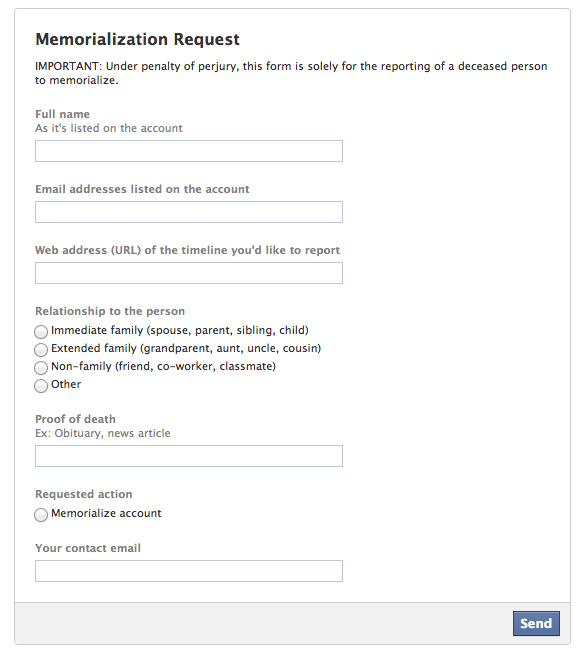

Private universities’ right to restrict speech (and, to a lesser extent, public universities’ ability to make rules to maintain orderly conduct on campus) do extend to social networks. In a recent Minnesota Supreme Court case, Tatro v. University of Minnesota, it was decided that the University of Minnesota (a public school) did not violate a student’s First Amendment rights by punishing her for a satirical Facebook post. In general (and though the Minnesota case didn’t meet this litmus test), schools are allowed to limit off-campus or online speech that “materially and substantially” disrupts school activities — a standard that dates back to Tinker v. Des Moines (1969).

Moral of the story: college students should be aware of free speech laws and jurisprudence, and especially the extent to which one’s university can limit expression on and off campus, offline and online.