What remains for Rio after the Olympics?

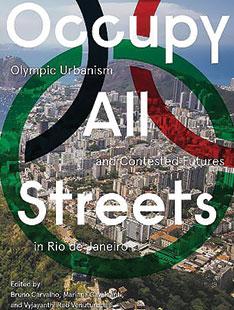

When cities host huge global events, they become the site of big dreams — and big disagreements. Last year’s summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro drew much criticism for large-scale development that displaced residents and exacerbated socioeconomic divides. It also spurred intense debate about what kind of city Rio should be. Those themes are explored in Occupy All Streets: Olympic Urbanism and Contested Futures (Terreform), co-edited by Rio native Bruno Carvalho, a professor in the Spanish and Portuguese department and co-director of the Princeton-Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism, and the Humanities. Carvalho spoke to PAW about last year’s Olympics and Rio’s past, present, and future.

When cities host huge global events, they become the site of big dreams — and big disagreements. Last year’s summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro drew much criticism for large-scale development that displaced residents and exacerbated socioeconomic divides. It also spurred intense debate about what kind of city Rio should be. Those themes are explored in Occupy All Streets: Olympic Urbanism and Contested Futures (Terreform), co-edited by Rio native Bruno Carvalho, a professor in the Spanish and Portuguese department and co-director of the Princeton-Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism, and the Humanities. Carvalho spoke to PAW about last year’s Olympics and Rio’s past, present, and future.

In the book, you describe moments in history when different conceptions of Rio took hold. What were they?

We can think in terms of epithets: In the 1930s a Carnival song popularized Rio as the “Marvelous City,” and it became the city anthem in the 1960s. But the epithet had come about in the context of early 20th-century urban reforms that tried to reinvent Brazil in a more modern, elitist, Paris-inspired mold, and it excluded the majority of the city that didn’t conform to this image.

Another epithet, which became very dominant in the 1990s, is this idea of the “Divided City,” characterized by urban violence, political crisis, and a persistent socioeconomic abyss — symbolized by the favelas versus the upscale waterfront residential buildings. A more recent epithet, which City Hall tried to push in the last few years, is Rio as “Olympic City.” Read more