By Liz Fuller-Wright, Office of Communications

The 2015 Paris climate agreement sought to stabilize global temperatures by limiting warming to well below 2.0 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue limiting warming even further, to 1.5 C.

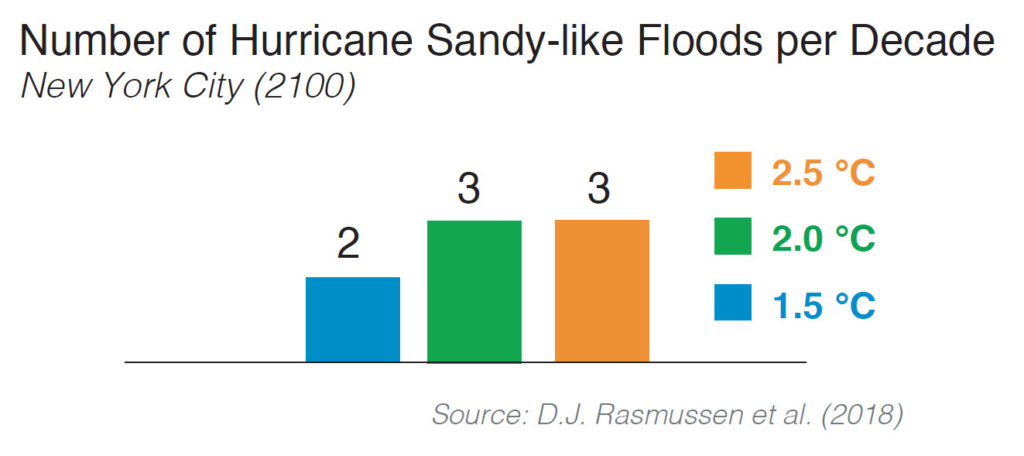

To quantify what that would mean for people living in coastal areas, a group of researchers employed a global network of tide gauges and a local sea level projection framework to explore differences in the frequency of storm surges and other extreme sea-level events across three scenarios: global temperature increases of 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 C.

They concluded that by 2150, the seemingly small difference between an increase of 1.5 and 2.0 C would mean the permanent inundation of lands currently home to about 5 million people, including 60,000 who live on small island nations.

The study, conducted by researchers at Princeton University and colleagues at Rutgers and Tufts Universities, the independent scientific organization Climate Central, and ICF International, was published in the journal Environmental Research Letters on March 15, 2018.

“People think the Paris Agreement is going to save us from harm from climate change, but we show that even under the best-case climate policy being considered today, many places will still have to deal with rising seas and more frequent coastal floods,” said D.J Rasmussen, a graduate student in Princeton’s Program in Science, Technology and Environmental Policy in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, and first author of the study.

The researchers found that higher temperatures will make extreme sea level events much more common. They used long-term hourly tide gauge records and extreme value theory to estimate present and future return periods of extreme sea-level events through the 22nd century. Under the 1.5 C scenario, the frequency of extreme sea level events is still expected to increase. For example, by the end of the 21st century, New York City is expected to experience one Hurricane Sandy-like flood event every five years.

Extreme sea levels can arise from high tides or storm surge or a combination of surge and tide (sometimes called the storm tide). When driven by hurricanes or other large storms, extreme sea levels flood coastal areas, threatening life and property. Rising mean sea levels are already magnifying the frequency and severity of extreme sea levels, and experts predict that by the end of the century, coastal flooding may be among the costliest impacts of climate change in some regions.

Future extreme events will be exacerbated by the rising global sea level, which in turn depends on the trajectory of global mean surface temperature. Even if global temperatures are stabilized, sea levels are expected to continue to rise for centuries, due to the fact that carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for a long time and the ice sheets are slow to respond to warming.

Overall, the researchers predicted that by the end of the century, a 1.5 C temperature increase could drive the global mean sea level up by roughly 1.6 feet (48 cm) while a 2.0 C increase will raise oceans by about 1.8 feet (56 cm) and a 2.5 C increase will raise sea level by an estimated 1.9 feet (58 cm).

The research team included Klaus Bittermann, a postdoctoral researcher at Tufts University who is associated with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany; Maya Buchanan, who earned a doctorate in 2017 from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and is now at ICF International; Scott Kulp, a senior computational scientist and senior developer for the Program on Sea Level Rise at Climate Central, an independent organization of scientists and journalists located in Princeton, NJ; Benjamin Strauss, who received a Ph.D. in 2007 from Princeton’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and is chief scientist at Climate Central; and Robert Kopp, a professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Rutgers University.

The senior author on the study was Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute. Kopp developed the sea level projection framework, and Buchanan, Kopp, and Oppenheimer developed the flood projection framework. Researchers at Climate Central conducted the population inundation analysis.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (grants EAR-1520683 and ICER-1663807), the Rhodium Group as part of the Climate Impact Lab consortium, and NASA (grant 80NSSC17K0698).

“Extreme sea level implications of 1.5 °C, 2.0 °C, and 2.5 °C temperature stabilization targets in the 21st and 22nd centuries” by D.J Rasmussen, Klaus Bittermann, Maya Buchanan, Scott Kulp, Benjamin Strauss, Robert Kopp, and Michael Oppenheimer was published March 15, 2018 in Environmental Research Letters. (doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaac87).

You must be logged in to post a comment.