By Morgan Kelly, Office of Communications

Imagine someone spent months researching new cities to call home using low-resolution images of unidentified skylines. The pictures were taken from several miles away with a camera intended for portraits, and at sunset. From these fuzzy snapshots, that person claims to know the city’s air quality, the appearance of its buildings, and how often it rains.

This technique is similar to how scientists often characterize the atmosphere — including the presence of water and oxygen — of planets outside of Earth’s solar system, known as exoplanets, according to a review of exoplanet research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A planet’s atmosphere is the gateway to its identity, including how it was formed, how it developed and whether it can sustain life, stated Adam Burrows, author of the review and a Princeton University professor of astrophysical sciences.

But the dominant methods for studying exoplanet atmospheres are not intended for objects as distant, dim and complex as planets trillions of miles from Earth, Burrows said. They were instead designed to study much closer or brighter objects, such as planets in Earth’s solar system and stars.

Nonetheless, scientific reports and the popular media brim with excited depictions of Earth-like planets ripe for hosting life and other conclusions that are based on vague and incomplete data, Burrows wrote in the first in a planned series of essays that examine the current and future study of exoplanets. Despite many trumpeted results, few “hard facts” about exoplanet atmospheres have been collected since the first planet was detected in 1992, and most of these data are of “marginal utility.”

The good news is that the past 20 years of study have brought a new generation of exoplanet researchers to the fore that is establishing new techniques, technologies and theories. As with any relatively new field of study, fully understanding exoplanets will require a lot of time, resources and patience, Burrows said.

“Exoplanet research is in a period of productive fermentation that implies we’re doing something new that will indeed mature,” Burrows said. “Our observations just aren’t yet of a quality that is good enough to draw the conclusions we want to draw.

“There’s a lot of hype in this subject, a lot of irrational exuberance. Popular media have characterized our understanding as better than it actually is,” he said. “They’ve been able to generate excitement that creates a positive connection between the astrophysics community and the public at large, but it’s important not to hype conclusions too much at this point.”

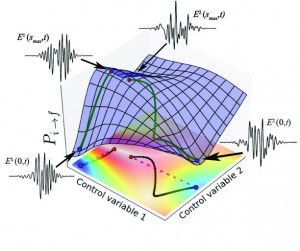

The majority of data on exoplanet atmospheres come from low-resolution photometry, which captures the variation in light and radiation an object emits, Burrows reported. That information is used to determine a planet’s orbit and radius, but its clouds, surface, and rotation, among other factors, can easily skew the results. Even newer techniques such as capturing planetary transits — which is when a planet passes in front of its star, and was lauded by Burrows as an unforeseen “game changer” when it comes to discovering new planets — can be thrown off by a thick atmosphere and rocky planet core.

All this means that reliable information about a planet can be scarce, so scientists attempt to wring ambitious details out of a few data points. “We have a few hard-won numbers and not the hundreds of numbers that we need,” Burrows said. “We have in our minds that exoplanets are very complex because this is what we know about the planets in our solar system, but the data are not enough to constrain even a fraction of these conceptions.”

Burrows emphasizes that astronomers need to acknowledge that they will never achieve a comprehensive understanding of exoplanets through the direct-observation, stationary methods inherited from the exploration of Earth’s neighbors. He suggests that exoplanet researchers should acknowledge photometric interpretations as inherently flawed and ambiguous. Instead, the future of exoplanet study should focus on the more difficult but comprehensive method of spectrometry, wherein the physical properties of objects are gauged by the interaction of its surface and elemental features with light wavelengths, or spectra. Spectrometry has been used to determine the age and expansion of the universe.

Existing telescopes and satellites are likewise vestiges of pre-exoplanet observation. Burrows calls for a mix of small, medium and large initiatives that will allow the time and flexibility scientists need to develop tools to detect and analyze exoplanet spectra. He sees this as a challenge in a research environment that often puts quick-payback results over deliberate research and observation. Once scientists obtain high-quality spectral data, however, Burrows predicted, “Many conclusions reached recently about exoplanet atmospheres will be overturned.”

“The way we study planets out of the solar system has to be radically different because we can’t ‘go’ to those planets with satellites or probes,” Burrows said. “It’s much more an observational science. We have to be detectives. We’re trying to find clues and the best clues since the mid-19th century have been in spectra. It’s the only means of understanding the atmosphere of these planets.”

A longtime exoplanet researcher, Burrows predicted the existence of “hot-Jupiter” planets — gas planets similar to Jupiter but orbiting very close to the parent star — in a paper in the journal Nature months before the first such planet, 51 Pegasi b, was discovered in 1995.

Citation: Burrows, Adam S. 2014. Spectra as windows into exoplanet atmospheres. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Article first published online: Jan. 13, 2014. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1304208111

You must be logged in to post a comment.