By Catherine Zandonella, Office of the Dean for Research

Understanding how genes act in specific tissues is critical to our ability to combat many human diseases, from heart disease to kidney failure to cancer. Yet isolating individual cell types for study is impossible for most human tissues.

A new method developed by researchers at Princeton University and the University of Michigan called “in silico nano-dissection” uses computers rather than scalpels to separate and identify genes from specific cell types, enabling the systematic study of genes involved in diseases.

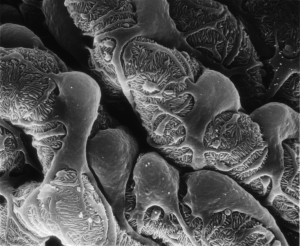

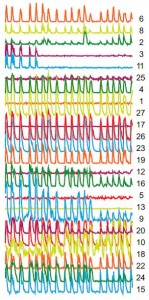

The team used the new method to successfully identify genes expressed in cells known as podocytes — the “work-horses” of the kidney — that malfunction in kidney disease. The investigators showed that certain patterns of activity of these genes were correlated with the severity of kidney impairment in patients, and that the computer-based approach was significantly more accurate than existing experimental methods in mice at identifying cell-lineage-specific genes. The study was published in the journal Genome Research.

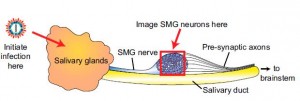

Using this technique, researchers can now examine the genes from a section of whole tissue, such as a biopsied section of the kidney, for specific signatures associated with certain cell types. By evaluating patterns of gene expression under different conditions in these cells, a computer can use machine-learning techniques to deduce which types of cells are present. The system can then identify which genes are expressed in the cell type in which they are interested. This information is critical both in defining novel disease biomarkers and in selecting potential new drug targets.

By applying the new method to kidney biopsy samples, the researchers identified at least 136 genes as expressed specifically in podocytes. Two of these genes were experimentally shown to be able to cause kidney disease. The authors also demonstrated that in silico nano-dissection can be used for cells other than those found in the kidney, suggesting that the method is useful for the study of a range of diseases.

The computational method was significantly more accurate than another commonly used technique that involves isolating specific cell types in mice. The nano-dissection method’s accuracy was 65% versus 23% for the mouse method, as evaluated by a time-consuming process known as immunohistochemistry which involves staining each gene of interest to study its expression pattern.

The research was co-led by Olga Troyanskaya, a professor of computer science and the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton, and Matthias Kretzler, a professor of computational medicine and biology at the University of Michigan. The first authors on the study were Wenjun Ju, a research assistant professor at the University of Michigan, and Casey Greene, now at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and a former postdoctoral fellow at Princeton.

The research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grant GM071966 to OGT and MK, by NIH grants RO1 HG005998 and DBI0546275 to OGT, by NIH center grant P50 GM071508, and by NIH R01 grant DK079912 and P30 DK081943 to MK. OGT also receives support from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

Wenjun Ju, Casey S Greene, Felix Eichinger, Viji Nair, Jeffery B Hodgin, Markus Bitzer, Young-suk Lee, Qian Zhu, Masami Kehata, Min Li, Song Jiang, Maria Pia Rastaldi, Clemens D Cohen, Olga G Troyanskaya and Matthias Kretzler. 2013. Defining cell-type specificity at the transcriptional level in human disease. Genome Research. Published in Advance August 15, 2013, doi: 10.1101/gr.155697.113.

You must be logged in to post a comment.