By Tien Nguyen

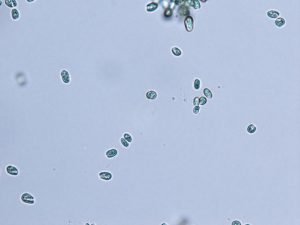

Photosynthetic algae have been refining their technique for capturing light for millions of years. As a result, these algae boast powerful light harvesting systems — proteins that absorb light to be turned into energy for the plants — that scientists have long aspired to understand and mimic for renewable energy applications.

Now, researchers at Princeton University have revealed a mechanism that enhances the light harvesting rates of the cryptophyte algae Chroomonas mesostigmatica. Published in the journal Chem on December 8, these findings provide valuable insights for the design of artificial light-harvesting systems such as molecular sensors and solar energy collectors.

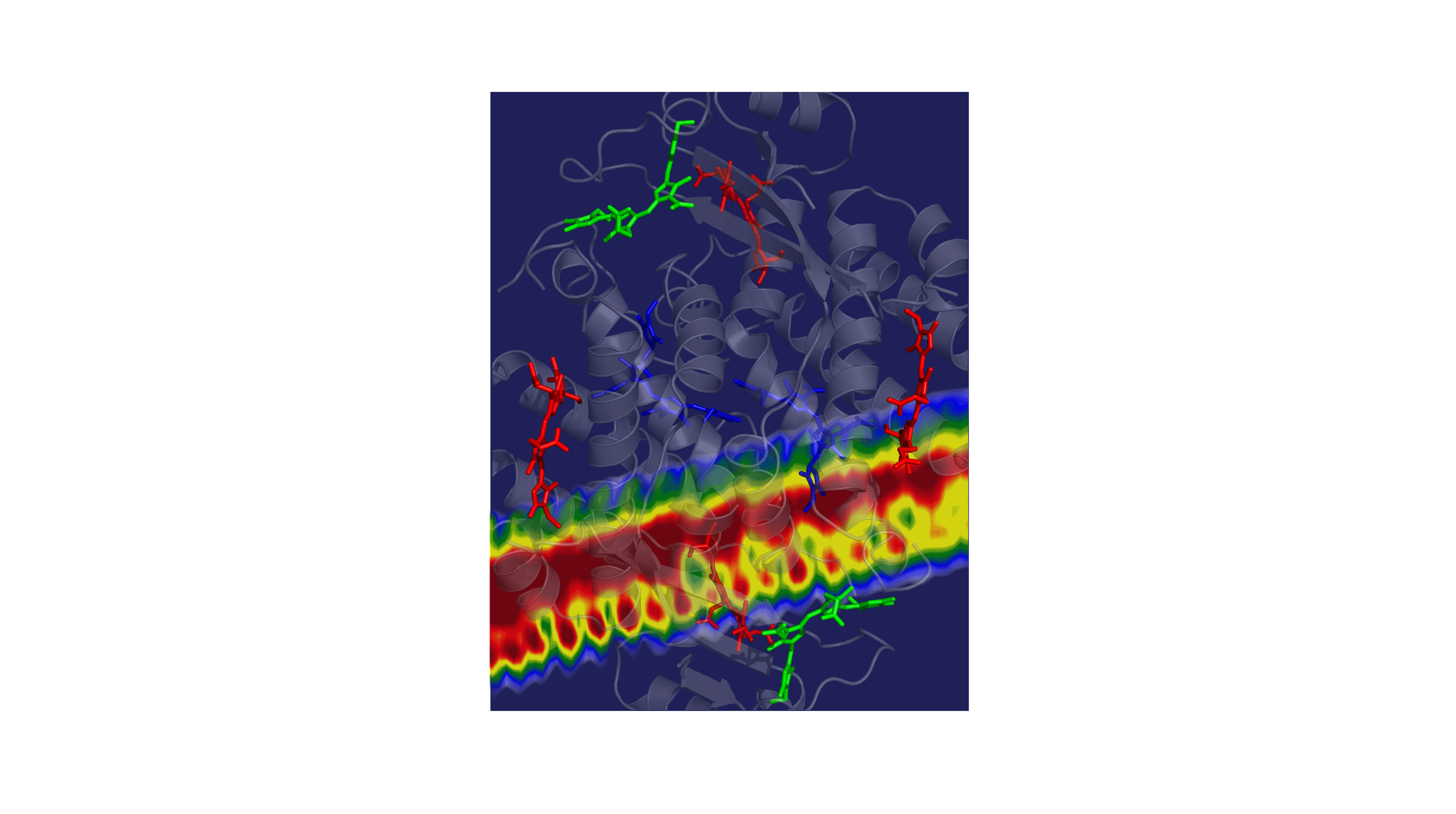

Cryptophyte algae often live below other organisms that absorb most of the sun’s rays. In response, the algae have evolved to thrive on wavelengths of light that aren’t captured by their neighbors above, mainly the yellow-green colors. The algae collects this yellow-green light energy and passes it through a network of molecules that converts it into red light, which chlorophyll molecules need to perform important photosynthetic chemistry.

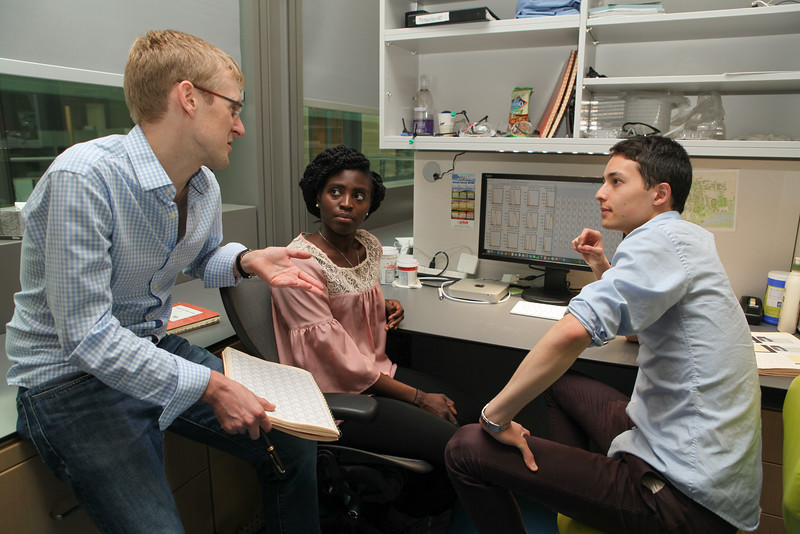

The speed of the energy transfer through the system has both impressed and perplexed the scientists that study them. In Gregory Scholes’ lab at Princeton University, predictions were always about three times slower than the observed rates. “The timescales that the energy is moved through the protein — we could never understand why the process so fast,” said Scholes, the William S. Tod Professor of Chemistry.

In 2010, Scholes’ team found evidence that the culprit behind these fast rates was a strange phenomenon called quantum coherence, in which molecules could share electronic excitation and transfer energy according to quantum mechanical probability laws instead of classical physics. But the research team couldn’t explain exactly how coherence worked to speed up the rates until now.

Using a sophisticated method enabled by ultrafast lasers, the researchers were able to measure the molecules’ light absorption and essentially track the energy flow through the system. Normally the absorption signals would overlap, making them impossible to assign to specific molecules within the protein complex, but the team was able to sharpen the signals by cooling the proteins down to very low temperatures, said Jacob Dean, lead author and postdoctoral researcher in the Scholes lab.

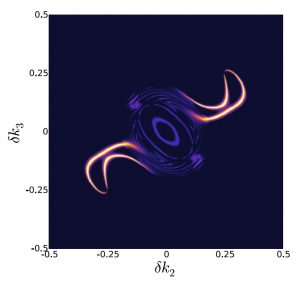

The researchers observed the system as energy was transferred from molecule to molecule, from high-energy green light to lower energy red light, with excess energy lost as vibrational energy. These experiments revealed a particular spectral pattern that was a ‘smoking gun’ for vibrational resonance, or vibrational matching, between the donor and acceptor molecules, Dean said.

This vibrational matching allowed energy to be transferred much faster than it otherwise would be by distributing the excitation between molecules. This effect provided a mechanism for the previously reported quantum coherence. Taking this redistribution into account, the researchers recalculated their prediction and landed on a rate that was about three times faster.

“Finally the prediction is in the right ballpark,” Scholes said. “Turns out that it required this quite different, surprising mechanism.”

The Scholes lab plans to study related proteins to investigate if this mechanism is operative in other photosynthetic organisms. Ultimately, scientists hope to create light-harvesting systems with perfect energy transfer by taking inspiration and design principles from these finely tuned yet extremely robust light-harvesting proteins. “This mechanism is one more powerful statement of the optimality of these proteins,” Scholes said.

Read the full article here:

Dean, J. C.; Mirkovic, T.; Toa, Z. S. D.; Oblinsky, D. G.; Scholes, G. D. “Vibronic Enhancement of Algae Light Harvesting.” Chem 2016, 1, 858.

You must be logged in to post a comment.