By Pooja Makhijani for the Department of Chemistry

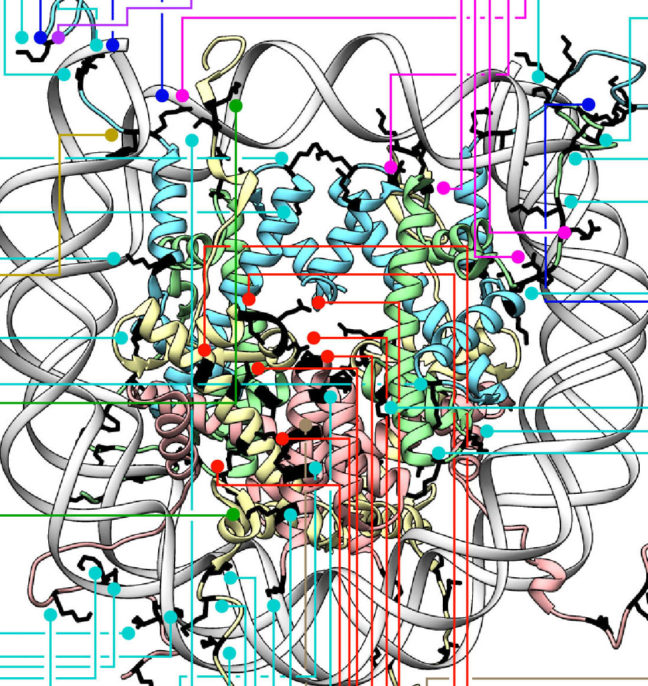

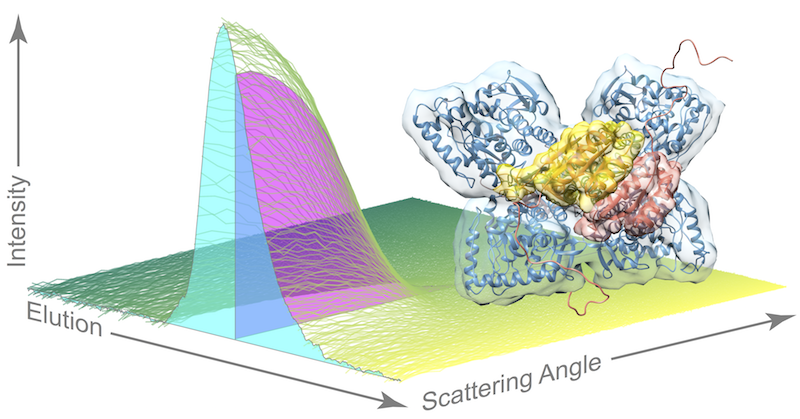

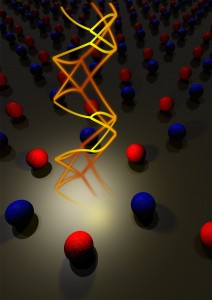

Chromatin remodelers — protein machines that pack and unpack chromatin, the tightly wound DNA-protein complex in cell nuclei — are essential and powerful regulators for critical cellular processes, such as replication, recombination and gene transcription and repression. In a new study published Aug. 2 in the journal Nature, a team led by researchers from Princeton University unravels more details on how a class of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers, called ISWI, regulate access to genetic information.

The researchers reported that ISWI remodelers use a structural feature of the nucleosome, known as the “acidic patch,” to remodel chromatin. The nucleosome is the fundamental structural subunit of chromatin, and is often compared to thread wrapped around a spool.

“The acidic patch is a negatively charged surface, presented on each face of the nucleosome disc, that is formed by amino acids contributed by two different histone proteins, H2A and H2B,” said Geoffrey Dann, a graduate student in the Department of Molecular Biology at Princeton and the study’s lead author. “Histone proteins are overall very positively charged, which makes the negatively charged acidic patch region of the nucleosome very unique. Recognition of the acidic patch has never before been implicated in chromatin remodeling.”

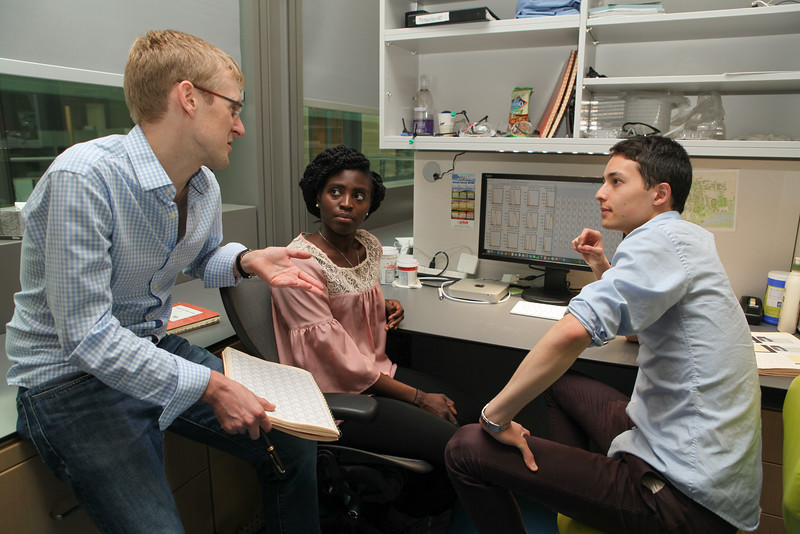

The research was conducted in the laboratory of Tom Muir, the Van Zandt Williams Jr. Class of 1965 Professor of Chemistry and chair of the Department of Chemistry. Research in the Muir group centers on elucidating the physiochemical basis of protein functions in biomedically relevant systems.

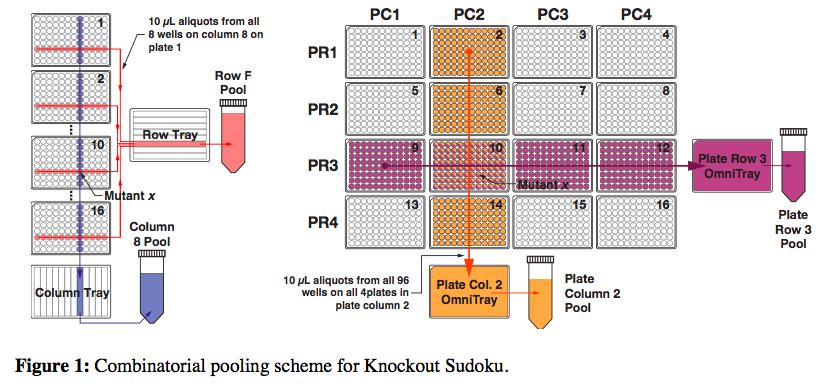

Because ISWI remodelers are known to interact extensively with nucleosomes, the researchers hypothesized that signals, in the form of chemical modifications on histone proteins embedded within nucleosomes, communicate to the remodelers on which nucleosome to act. Using high throughput screening technology, an assay process often used in drug discovery, allowed the researchers to quickly conduct tens of thousands of biochemical measurements to test their assumptions. “The number of chromatin modifications known to exist in vivo is astronomical,” Dann said.

Not only did the experiments reveal that ISWI remodelers use the “acidic patch” to remodel chromatin, but also determined that remodeling enzymes outside the family of ISWI remodelers also use this structural feature, “suggesting that this feature may be a general requirement for chromatin remodeling to occur,” Dann said.

Certain chemical modifications that act on histone proteins that are adjacent to the acidic patch also have the ability to enhance or inhibit ISWI remodeling activity, he explained. “A handful of other proteins are known to engage the acidic patch in their interaction with chromatin as well, and we also found that the biochemistry of several of these proteins was affected by such modifications. Interestingly, each protein tested had its own signature response to this collection of modifications.”

The high throughput screening technology method also generated a vast library of data to drive the design of future studies geared toward further understanding ISWI regulation. “This study generated an immense amount of data pointing to many other novel regulatory inputs, in the form of chromatin modifications, into ISWI remodeling activity,” Dann said. “A long-term goal in our lab is to use this data resource as a launch pad for additional studies investigating how chromatin modifications affect ISWI remodeling, and how this plays into the various roles ISWI remodelers assume in the cell.”

Their findings may also identify a new instrument in cells’ molecular repertoire of chromatin-remodeling tools and spur investigations into potential cancer therapeutic targets. “Mutations in the acidic patch are known to occur in certain types of human cancers, which underscores the emerging importance of the acidic patch in chromatin biology,” Dann said.

The study, “ISWI chromatin remodellers sense nucleosome modifications to determine substrate preference,” was published Aug. 2 by Nature. doi:10.1038/nature23671

The authors at Princeton University were Geoffrey P. Dann, Glen Liszczak, John D. Bagert, Manuel M. Müller, Uyen T. T. Nguyen, Felix Wojcik, Zachary Z. Brown, Jeffrey Bos, Rasmus Pihl, Samuel B. Pollock, Katharine L. Diehl and Tom W. Muir. Also contributing to the study were Tatyana Panchenko & C. David Allis at The Rockefeller University.

The research was funded in part by the German Research Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (GM112365, R01 GM107047).

Read the full article here: https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaap/ncurrent/full/nature23671.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.