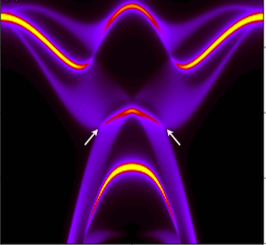

Magna plumes and hotspots, such as the one below Yellowstone, are visible in this subterranean simulation. (Credit: David Pugmire, ORNL)

By Jonathan Hines, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Because of Earth’s layered composition, scientists have often compared the basic arrangement of its interior to that of an onion. There’s the familiar thin crust of continents and ocean floors; the thick mantle of hot, semisolid rock; the molten metal outer core; and the solid iron inner core.

But unlike an onion, peeling back Earth’s layers to better explore planetary dynamics isn’t an option, forcing scientists to make educated guesses about our planet’s inner life based on surface-level observations. Clever imaging techniques devised by computational scientists, however, offer the promise of illuminating Earth’s subterranean secrets.

Using advanced modeling and simulation, seismic data generated by earthquakes, and one of the world’s fastest supercomputers, a team led by Jeroen Tromp of Princeton University is creating a detailed 3-D picture of Earth’s interior. Currently, the team is focused on imaging the entire globe from the surface to the core–mantle boundary, a depth of 1,800 miles.

These high-fidelity simulations add context to ongoing debates related to Earth’s geologic history and dynamics, bringing prominent features like tectonic plates, magma plumes, and hotspots into view. In September 2016, the team published a paper in Geophysical Journal International on its first-generation global model. Created using data from 253 earthquakes captured by seismograms scattered around the world, the team’s model is notable for its global scope and high scalability.

“This is the first global seismic model where no approximations—other than the chosen numerical method—were used to simulate how seismic waves travel through the Earth and how they sense heterogeneities,” said Ebru Bozdag, a coprincipal investigator of the project and an assistant professor of geophysics at the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis. “That’s a milestone for the seismology community. For the first time, we showed people the value and feasibility of running these kinds of tools for global seismic imaging.”

The project’s genesis can be traced to a seismic imaging theory first proposed in the 1980s. To fill in gaps within seismic data maps, the theory posited a method called adjoint tomography, an iterative full-waveform inversion technique. This technique leverages more information than competing methods, using forward waves that travel from the quake’s origin to the seismic receiver and adjoint waves, which are mathematically derived waves that travel from the receiver to the quake.

The problem with testing this theory? “You need really big computers to do this,” Bozdag said, “because both forward and adjoint wave simulations are performed in 3-D numerically.”

In 2012, just such a machine arrived in the form of the Titan supercomputer, a 27-petaflop Cray XK7 managed by the US Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at DOE’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After trying out its method on smaller machines, Tromp, who is Princeton’s Blair Professor of Geology and a professor of geosciences and applied and computational mathematics, and his team gained access to Titan in 2013 through the Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment, or INCITE, program.

Working with OLCF staff, the team continues to push the limits of computational seismology to deeper depths.

Stitching together seismic slices

When an earthquake strikes, the release of energy creates seismic waves that often wreak havoc for life at the surface. Those same waves, however, present an opportunity for scientists to peer into the subsurface by measuring vibrations passing through the Earth.

As seismic waves travel, seismograms can detect variations in their speed. These changes provide clues about the composition, density, and temperature of the medium the wave is passing through. For example, waves move slower when passing through hot magma, such as mantle plumes and hotspots, than they do when passing through colder subduction zones, locations where one tectonic plate slides beneath another.

Each seismogram represents a narrow slice of the planet’s interior. By stitching many seismograms together, researchers can produce a 3-D global image, capturing everything from magma plumes feeding the Ring of Fire, to Yellowstone’s hotspots, to subducted plates under New Zealand.

This process, called seismic tomography, works in a manner similar to imaging techniques employed in medicine, where 2-D x-ray images taken from many perspectives are combined to create 3-D images of areas inside the body.

In the past, seismic tomography techniques have been limited in the amount of seismic data they can use. Traditional methods forced researchers to make approximations in their wave simulations and restrict observational data to major seismic phases only. Adjoint tomography based on 3-D numerical simulations employed by Tromp’s team isn’t constrained in this way. “We can use the entire data—anything and everything,” Bozdag said.

Running its GPU version of the SPECFEM3D_GLOBE code, Tromp’s team used Titan to apply full-waveform inversion at a global scale. The team then compared these “synthetic seismograms” with observed seismic data supplied by the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS), calculating the difference and feeding that information back into the model for further optimization. Each repetition of this process improves global models.

“This is what we call the adjoint tomography workflow, and at a global scale it requires a supercomputer like Titan to be executed in reasonable timeframe,” Bozdag said. “For our first-generation model, we completed 15 iterations, which is actually a small number for these kinds of problems. Despite the small number of iterations, our enhanced global model shows the power of our approach. This is just the beginning, however.”

Automating to augment

For its initial global model, Tromp’s team selected earthquake events that registered between 5.8 and 7 on the Richter scale—a standard for measuring earthquake intensity. That range can be extended slightly to include more than 6,000 earthquakes in the IRIS database—about 20 times the amount of data used in the original model.

Getting the most out of all the available data requires a robust automated workflow capable of accelerating the team’s iterative process. Collaborating with OLCF staff, Tromp’s team has made progress toward this goal.

For the team’s first-generation model, Bozdag carried out each step of the workflow manually, taking about a month to complete one model update. Team members Matthieu Lefebvre, Wenjie Lei, and Youyi Ruan of Princeton University and the OLCF’s Judy Hill developed new automated workflow processes that hold the promise of reducing that cycle to a matter of days.

“Automation will really make it more efficient, and it will also reduce human error, which is pretty easy to introduce,” Bozdag said.

Additional support from OLCF staff has contributed to the efficient use and accessibility of project data. Early in the project’s life, Tromp’s team worked with the OLCF’s Norbert Podhorszki to improve data movement and flexibility. The end result, called Adaptable Seismic Data Format (ASDF), leverages the Adaptable I/O System (ADIOS) parallel library and gives Tromp’s team a superior file format to record, reproduce, and analyze data on large-scale parallel computing resources.

In addition, the OLCF’s David Pugmire helped the team implement in situ visualization tools. These tools enabled team members to check their work more easily from local workstations by allowing visualizations to be produced in conjunction with simulation on Titan, eliminating the need for costly file transfers.

“Sometimes the devil is in the details, so you really need to be careful and know what you’re looking at,” Bozdag said. “David’s visualization tools help us to investigate our models and see what is there and what is not.”

With visualization, the magnitude of the team’s project comes to light. The billion-year cycle of molten rock rising from the core–mantle boundary and falling from the crust—not unlike the motion of globules in a lava lamp—takes form, as do other geologic features of interest.

At this stage, the resolution of the team’s global model is becoming advanced enough to inform continental studies, particularly in regions with dense data coverage. Making it useful at the regional level or smaller, such as the mantle activity beneath Southern California or the earthquake-prone crust of Istanbul, will require additional work.

“Most global models in seismology agree at large scales but differ from each other significantly at the smaller scales,” Bozdag said. “That’s why it’s crucial to have a more accurate image of Earth’s interior. Creating high-resolution images of the mantle will allow us to contribute to these discussions.”

Digging deeper

To improve accuracy and resolution further, Tromp’s team is experimenting with model parameters under its most recent INCITE allocation. For example, the team’s second-generation model will introduce anisotropic inversions, which are calculations that better capture the differing orientations and movement of rock in the mantle. This new information should give scientists a clearer picture of mantle flow, composition, and crust–mantle interactions.

Additionally, team members Dimitri Komatitsch of Aix-Marseille University in France and Daniel Peter of King Abdullah University in Saudi Arabia are leading efforts to update SPECFEM3D_GLOBE to incorporate capabilities such as the simulation of higher-frequency seismic waves. The frequency of a seismic wave, measured in Hertz, is equivalent to the number of waves passing through a fixed point in one second. For instance, the current minimum frequency used in the team’s simulation is about 0.05 hertz (1 wave per 20 seconds), but Bozdag said the team would also like to incorporate seismic waves of up to 1 hertz (1 wave per second). This would allow the team to model finer details in the Earth’s mantle and even begin mapping the Earth’s core.

To make this leap, Tromp’s team is preparing for Summit, the OLCF’s next-generation supercomputer. Set to arrive in 2018, Summit will provide at least five times the computing power of Titan. As part of the OLCF’s Center for Accelerated Application Readiness, Tromp’s team is working with OLCF staff to take advantage of Summit’s computing power upon arrival.

“With Summit, we will be able to image the entire globe from crust all the way down to Earth’s center, including the core,” Bozdag said. “Our methods are expensive—we need a supercomputer to carry them out—but our results show that these expenses are justified, even necessary.”

“Global Adjoint Tomography: First-Generation Model,” Ebru Bozdag, Daniel Peter, Matthieu Lefebvre, Dimitri Komatitsch, Jeroen Tromp, Judith Hill, Norbert Podhorszki, and David Pugmire, Geophysical Journal International 207, no. 3 (2016): 1739–1766.

This article appears courtesy of Oak Ridge National Laboratory. See the original article.

Oak Ridge National Laboratory is supported by the US Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, the Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

You must be logged in to post a comment.